BIN-PHYLO-Tree building

Building Phylogenetic Trees

Keywords: Calculating phylogenetic trees; tree visualization

Contents

This unit is under development. There is some contents here but it is incomplete and/or may change significantly: links may lead to nowhere, the contents is likely going to be rearranged, and objectives, deliverables etc. may be incomplete or missing. Do not work with this material until it is updated to "live" status.

Abstract

...

This unit ...

Prerequisites

You need the following preparation before beginning this unit. If you are not familiar with this material from courses you took previously, you need to prepare yourself from other information sources:

- Evolution: Theory of evolution; variation, neutral drift and selection.

You need to complete the following units before beginning this one:

- BIN-PHYLO-Data_preparation (Preparing Data for Phylogenetic Analysis)

- FND-STA-Bayes_theorem (Bayes' theorem)

Objectives

...

Outcomes

...

Deliverables

- Time management: Before you begin, estimate how long it will take you to complete this unit. Then, record in your course journal: the number of hours you estimated, the number of hours you worked on the unit, and the amount of time that passed between start and completion of this unit.

- Journal: Document your progress in your Course Journal. Some tasks may ask you to include specific items in your journal. Don't overlook these.

- Insights: If you find something particularly noteworthy about this unit, make a note in your insights! page.

Evaluation

Evaluation: NA

- This unit is not evaluated for course marks.

Contents

Task:

- Read the introductory notes on building phylogenetic trees.

The result of the tree construction is a decision about the most likely evolutionary relationships. Fundamentally, tree-construction programs decide which sequences had common ancestors.

- "Distance based" and "Parsimony based" methods are fast, but less acurate.

Distance based phylogeny programs start by using sequence comparisons to estimate evolutionary distances:

- they apply a model of evolution such as a mutation data matrix, to calculate a score for each pair of sequences,

- this score is stored in a "distance matrix" ...

- ... and used to estimate a tree that groups sequences with close relationships together. (e.g. by using an NJ, Neigbor Joining, algorithm).

They are fast, can work on large numbers of sequences, but are less accurate if genes evolve at different rates.

Parsimony based phylogeny programs build a tree that minimizes the number of mutation events that are required to get from a common ancestral sequence to all observed sequences. They take all columns into account, not just a single number per sequence pair, as the Distance Methods do. For closely related sequences they work very well, but they construct inaccurate trees when they can't make good estimates for the required number of sequence changes.

- "Maximum Likelihood" and "Bayesian" methods are accurate, but can take up very significant computational resources.

ML, or Maximum Likelihood methods attempt to find the tree for which the observed sequences would be the most likely under a particular evolutionary model. They are based on a rigorous statistical framework and yield the most robust results. But they are also quite compute intensive and a tree of the size that we are building in this assignment is a challenge for the resources of common workstation (runs about an hour on my computer). If the problem is too large, one may split a large problem into smaller, obvious subtrees (e.g. analysing orthologues as a group, only including a few paralogues for comparison) and then merge the smaller trees; this way even very large problems can become tractable.

ML methods suffer less from "long-branch attraction" - the phenomenon that weakly similar sequences can be grouped inappropriately close together in a tree due to spuriously shared differences.

Bayesian methods don't estimate the tree that gives the highest likelihood for the observed data, but find the most probable tree, given the data that has been observed. If you think this sounds conceptually similar to ML methods, then you are not wrong. However, the approaches employ very different algorithms. And Bayesian methods need a "prior" on trees before observation.

Calculating trees

In this section we perform the actual phylogenetic calculation.

Task:

- Download the PHYLIP suite of programs from the Phylip homepage and install it on your computer.

- Return to the RStudio project and work through PART FOUR: Calculating trees.

Analysing your tree

In order to analyse your tree, you need a species tree as reference. This really is an absolute prerequisite to make your expectations about the observed tree explicit. Fortunately we have all species nicely documented in our database.

The reference species tree

Task:

- Navigate to the NCBI Taxonomy page

- Execute the following R command to create an Entrez command that will retrieve all taxonomy records for the species in your database:

cat(paste(paste(c(myDB$taxonomy$ID, "83333"), "[taxid]", sep=""), collapse=" OR "))- Copy the Entrez command, and enter it into the search field of the NCBI taxonomy page. Click on Search. The resulting page should have twelve species listed - ten "reference" fungi, E. coli (as the outgroup), and MYSPE. Make sure MYSPE is included! If it's not there, you did something wrong that needs to be fixed.

- Click on the Summary options near the top-left of the page, and select Common Tree. This places all the species into the universal tree of life and identifies their relationships.

- At the top, there is an option to Save as ... and the option to select a format to save the tree in. Select Phylip Tree as the format and click the Save as button. The file

phyliptree.phywill be downloaded to your computer into your default download directory. Move it to the directory you have defined asPROJECTDIR.

- Open the file in a text-editor. This is a tree, specified in the so-called "Newick format". The topology of the tree is defined through the brackets, and the branch-lengths are all the same: this is a cladogram, not a phylogram. The tree contains the long names for the species/strains and for our purposes we really need the "biCodes" instead. I can't think of a very elegant way to make that change programmatically, so just go ahead and replace the species names (not the taxonomic ranks though) with their biCode in your text editor. Remove all the single quotes, and replace any remaining blanks in names with an underscore. Take care however not to delete any colons or parentheses. Save the file.

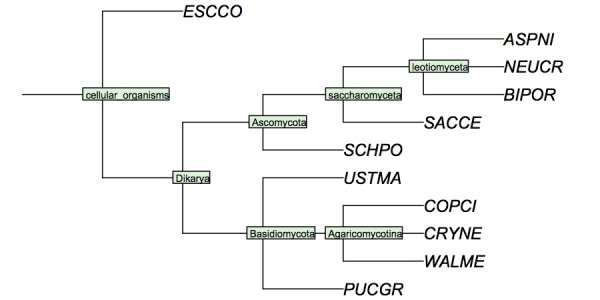

My version looks like this - Your version must have MYSPE somewhere in the tree..

( 'ESCCO':4, ( ( 'PUCGR':4, 'USTMA':4, ( 'WALME':4, 'COPCI':4, 'CRYNE':4 )Agaricomycotina:4 )Basidiomycota:4, ( ( ( 'ASPNI':4, 'BIPOR':4, 'NEUCR':4 )leotiomyceta:4, 'SACCE':4 )saccharomyceta:4, 'SCHPO':4 )Ascomycota:4 )Dikarya:4 )'cellular organisms':4;

- Now read the tree in R and plot it.

# Download the EDITED phyliptree.phy

orgTree <- read.tree("phyliptree.phy")

# Plot the tree in a new window

dev.new(width=6, height=3)

plot(orgTree, cex=1.0, root.edge=TRUE, no.margin=TRUE)

nodelabels(text=orgTree$node.label, cex=0.6, adj=0.2, bg="#D4F2DA")

I have constructed a cladogram for many of the species we are analysing, based on data published for 1551 fungal ribosomal sequences. The six reference species are included. Such reference trees from rRNA data are a standard method of phylogenetic analysis, supported by the assumption that rRNA sequences are monophyletic and have evolved under comparable selective pressure in all species.

Cladogram of the "reference" fungi studied in the assignments. This cladogram is based on a tree returned by the NCBI Common Tree. It is thus a digest of cladistic relationships, not a representation of a specific molecular phylogeny.

Alternatively, you can look up your species in the latest version of the species tree for the fungi and add it to the tree by hand while resolving the trifurcations. See:

| Ebersberger et al. (2012) A consistent phylogenetic backbone for the fungi. Mol Biol Evol 29:1319-34. (pmid: 22114356) |

|

[ PubMed ] [ DOI ] The kingdom of fungi provides model organisms for biotechnology, cell biology, genetics, and life sciences in general. Only when their phylogenetic relationships are stably resolved, can individual results from fungal research be integrated into a holistic picture of biology. However, and despite recent progress, many deep relationships within the fungi remain unclear. Here, we present the first phylogenomic study of an entire eukaryotic kingdom that uses a consistency criterion to strengthen phylogenetic conclusions. We reason that branches (splits) recovered with independent data and different tree reconstruction methods are likely to reflect true evolutionary relationships. Two complementary phylogenomic data sets based on 99 fungal genomes and 109 fungal expressed sequence tag (EST) sets analyzed with four different tree reconstruction methods shed light from different angles on the fungal tree of life. Eleven additional data sets address specifically the phylogenetic position of Blastocladiomycota, Ustilaginomycotina, and Dothideomycetes, respectively. The combined evidence from the resulting trees supports the deep-level stability of the fungal groups toward a comprehensive natural system of the fungi. In addition, our analysis reveals methodologically interesting aspects. Enrichment for EST encoded data-a common practice in phylogenomic analyses-introduces a strong bias toward slowly evolving and functionally correlated genes. Consequently, the generalization of phylogenomic data sets as collections of randomly selected genes cannot be taken for granted. A thorough characterization of the data to assess possible influences on the tree reconstruction should therefore become a standard in phylogenomic analyses. |

Task:

- Return to the RStudio project and continue with the script to its end. Note the deliverable at the end: to print out your trees and bring them to class.

Self-evaluation

If in doubt, ask! If anything about this learning unit is not clear to you, do not proceed blindly but ask for clarification. Post your question on the course mailing list: others are likely to have similar problems. Or send an email to your instructor.

About ...

Author:

- Boris Steipe <boris.steipe@utoronto.ca>

Created:

- 2017-08-05

Modified:

- 2017-08-05

Version:

- 0.1

Version history:

- 0.1 First stub

![]() This copyrighted material is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Follow the link to learn more.

This copyrighted material is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Follow the link to learn more.