Difference between revisions of "BIO Assignment Week 7"

m |

|||

| Line 288: | Line 288: | ||

Check it out - the question will be on the quiz. | Check it out - the question will be on the quiz. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Identifying Orthologs== |

| + | In the last assignment we discovered homologs to ''S. cerevisiae'' Mbp1 in YFO. Some of these will be orthologs to Mbp1, some will be paralogs. Some will have similar function, some will not. We discussed previously that genes that evolve under continuously similar evolutionary pressure should be most similar in sequence, and should have the most similar "function". | ||

| + | In this assignment we will define the YFO gene that is the most similar ortholog to ''S. cerevisiae'' Mbp1, and perform a multiple sequence alignment with it. | ||

| − | ; | + | Let us briefly review the basic concepts. |

| + | |||

| + | <div style="padding: 2px; background: #F0F1F7; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA; font-size:125%;color:#444444"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | ;All related genes are homologs. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Two central definitions about the mutual relationships between related genes go back to Walter Fitch who stated them in the 1970s: | ||

| + | <div style="padding: 2px; background: #F0F1F7; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA; font-size:125%;color:#444444"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | ;Orthologs have diverged after speciation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Paralogs have diverged after duplication. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

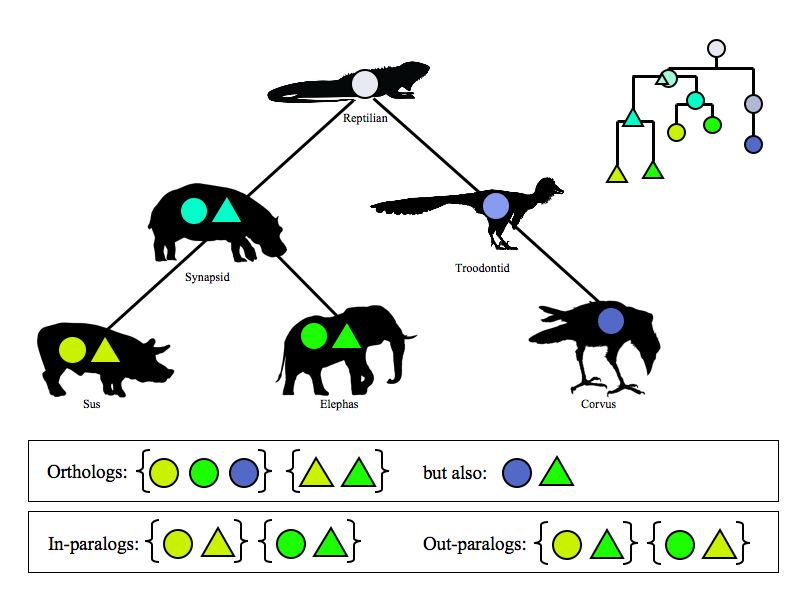

| + | [[Image:OrthologParalog.jpg|frame|none|'''Hypothetical evolutionary tree.''' A single gene evolves through two speciation events and one duplication event. A duplication occurs during the evolution from reptilian to synapsid. It is easy to see how this pair of genes (paralogs) in the ancestral synapsid gives rise to two pairs of genes in pig and elephant, respectively. All ''circle'' genes are mutually orthologs, they form a "cluster of orthologs". All genes within one species are mutual paralogs–they are so called ''in-paralogs''. The ''circle'' gene in pig and the ''triangle'' gene in the elephant are so-called ''out-paralogs''. Somewhat counterintuitively, the ''triangle'' gene in the pig and the ''circle'' gene in the raven are also orthologs - but this has to be, since the last common ancestor diverged by '''speciation'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The "phylogram" on the right symbolizes the amount of evolutionary change as proportional to height difference to the "root". It is easy to see how a bidirectional BLAST search will only find pairs of most similar orthologs. If applied to a group of species, bidirectional BLAST searches will find clusters of orthologs only (except if genes were lost, or there are anomalies in the evolutionary rate.)]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Defining orthologs== | ||

| + | |||

| + | To be reasonably certain about orthology relationships, we would need to construct and analyze detailed evolutionary trees. This is computationally expensive and the results are not always unambiguous either, as we will see in a later assignment. But a number of different strategies are available that use precomputed results to define orthologs. These are especially useful for large, cross genome surveys. They are less useful for detailed analysis of individual genes. Pay the sites a visit and try a search. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ;Orthologs by eggNOG | ||

| + | :The [http://eggnog.embl.de/ '''eggNOG'''] (evolutionary genealogy of genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups) database contains orthologous groups of genes at the EMBL. It seems to be continuously updtaed, the search functionality is reasonable and the results for yeast Mbp1 show many genes from several fungi. Importantly, there is only one gene annotated for each species. Alignments and trees are also available, as are database downloads for algorithmic analysis. | ||

| + | <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" data-expandtext="more..." data-collapsetext="less" style="width:800px"> | ||

| + | | ||

| + | <div class="mw-collapsible-content"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{#pmid: 24297252}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ;Orthologs at OrthoDB | ||

| + | :[http://www.orthodb.org/ '''OrthoDB'''] includes a large number of species, among them all of our protein-sequenced fungi. However the search function (by keyword) retrieves many paralogs together with the orthologs, for example, the yeast Soc2 and Phd1 proteins are found in the same orthologous group these two are clearly paralogs. | ||

| + | <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" data-expandtext="more..." data-collapsetext="less" style="width:800px"> | ||

| + | | ||

| + | <div class="mw-collapsible-content"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{#pmid: 23180791}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ;Orthologs at OMA | ||

| + | [http://omabrowser.org/ '''OMA'''] (the Orthologous Matrix) maintained at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology contains a large number of orthologs from sequenced genomes. Searching with <code>MBP1_YEAST</code> (this is the Swissprot ID) as a "Group" search finds the correct gene in EREGO, KLULA, CANGL and SACCE. But searching with the sequence of the ''Ustilago maydis'' ortholog does not find the yeast protein, but the orthologs in YARLI, SCHPO, LACCBI, CRYNE and USTMA. Apparently the orthologous group has been split into several subgroups across the fungi. However as a whole the database is carefully constructed and available for download and API access; a large and useful resource. | ||

| + | <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" data-expandtext="more..." data-collapsetext="less" style="width:800px"> | ||

| + | | ||

| + | <div class="mw-collapsible-content"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{#pmid: 21113020}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ... see also the related articles, much innovative and carefully done work on automated orthologue definition by the Dessimoz group. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ;Orthologs by syntenic gene order conservation | ||

| + | :We will revisit this when we explore the UCSC genome browser. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ;Orthologs by RBM | ||

| + | :Defining it yourself. RBM (or: Reciprocal Best Match) is easy to compute and half of the work you have already done in [[BIO_Assignment_Week_3|Assignment 3]]. Get the ID for the gene which you have identified and annotated as the best BLAST match for Mbp1 in YFO and confirm that this gene has Mbp1 as the most significant hit in the yeast proteome. <small>The results are unambiguous, but there may be residual doubt whether these two best-matching sequences are actually the most similar orthologs.</small> | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{task|1= | ||

| + | # Navigate to the BLAST homepage. | ||

| + | # Paste the YFO RefSeq sequence identifier into the search field. (You don't have to search with sequences–you can search directly with an NCBI identifier '''IF''' you want to search with the full-length sequence.) | ||

| + | # Set the database to refseq, and restrict the species to ''Saccharomyces cerevisiae''. | ||

| + | # Run BLAST. | ||

| + | # Keep the window open for the next task. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The top hit should be yeast Mbp1 (NP_010227). E mail me your sequence identifiers if it is not. | ||

| + | If it is, you have confirmed the '''RBM''' or '''BBM''' criterion (Reciprocal Best Match or Bidirectional Best Hit, respectively). | ||

| + | |||

| + | <small>Technically, this is not perfectly true since you have searched with the APSES domain in one direction, with the full-length sequence in the other. For this task I wanted you to try the ''search-with-accession-number''. Therefore the procedural laxness, I hope it is permissible. In fact, performing the reverse search with the YFO APSES domain should actually be more stringent, i.e. if you find the right gene with the longer sequence, you are even more likely to find the right gene with the shorter one.</small> | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ;Orthology by annotation | ||

| + | :The NCBI precomputes BLAST results and makes them available at the RefSeq database entry for your protein. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{task|1= | ||

| + | # In your BLAST result page, click on the RefSeq link for your query to navigate to the RefSeq database entry for your protein. | ||

| + | # Follow the '''Blink''' link in the right-hand column under '''Related information'''. | ||

| + | # Restrict the view RefSeq under the "Display options" and to Fungi. | ||

| + | |||

| + | You should see a number of genes with low E-values and high coverage in other fungi - however this search is problematic since the full length gene across the database finds mostly Ankyrin domains. | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | You will find that '''all''' of these approaches yield '''some''' of the orthologs. But none finds them all. The take home message is: precomputed results are good for large-scale survey-type investigations, where you can't humanly process the information by hand. But for more detailed questions, careful manual searches are still indsipensable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" data-expandtext="Expand for crowdsourcing" data-collapsetext="Collapse"> | ||

| + | ;Orthology by crowdsourcing | ||

| + | :Luckily a crowd of willing hands has prepared the necessary sequences for you: in the section below you will find a link to the annotated and verified Mbp1 orthologs from last year's course :-) | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="mw-collapsible-content"> | ||

| + | We could call this annotation by many hands {{WP|Crowdsourcing|"crowdsourcing"}} - handing out small parcels of work to many workers, who would typically allocate only a small share of their time, but here the strength is in numbers and especially projects that organize via the Internet can tally up very impressive manpower, for free, or as {{WP|Microwork}}. These developments have some interest for bioinformatics: many of our more difficult tasks can not be easily built into an algorithm, language related tasks such as text-mining, or pattern matching tasks come to mind. Allocating this to a large number of human contributors may be a viable alternative to computation. A marketplace where this kind of work is already a reality is {{WP|Amazon Mechanical Turk|Amazon's "Mechanical Turk" Marketplace}}: programmers–"requesters"– use an open interface to post tasks for payment, "providers" from all over the world can engage in these. Tasks may include matching of pictures, or evaluating the aesthetics of competing designs. A quirky example I came across recently was when information designer David McCandless had 200 "Mechanical Turks" draw a small picture of their soul for his collection. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The name {{WP|The Turk|"Mechanical Turk"}} by the way relates to a famous ruse, when a Hungarian inventor and adventurer toured the imperial courts of 18<sup>th</sup> century Europe with an automaton, dressed in turkish robes and turban, that played chess at the grandmaster level against opponents that included Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin. No small mechanical feat in any case, it was only in the 19<sup>th</sup> century that it was revealed that the computational power was actually provided by a concealed human. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Are you up for some "Turking"? Before the next quiz, edit [http://biochemistry.utoronto.ca/steipe/abc/students/index.php/BCH441_2014_Assignment_7_RBM '''the Mbp1 RBM page on the Student Wiki] and include the RBM for Mbp1, for a 10% bonus on the next quiz. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | | ||

==Links and Resources== | ==Links and Resources== | ||

Revision as of 17:32, 4 October 2015

Assignment for Week 8

Phylogenetic Analysis

| < Assignment 7 | Assignment 9 > |

Note! This assignment is currently inactive. Major and minor unannounced changes may be made at any time.

Concepts and activities (and reading, if applicable) for this assignment will be topics on next week's quiz.

Contents

- Nothing in Biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.

- Theodosius Dobzhansky

... but does evolution make sense in the light of biology?

As we have seen in the previous assignments, the Mbp1 transcription factor has homologues in all other fungi, yet there is not always a clear one-to-one mapping between members of a family in distantly related species. It appears that various systems of APSES domain transcription factors have evolved independently. Of course this bears directly on our notion of function - what it means to say that two genes in different organisms have the "same" function. In case two organisms both have an orthologous gene for the same, distinct function, saying that the function is the same may be warranted. But what if that gene has duplicated in one species, and the two paralogues now perform different, related functions in one organism? Theses two are still orthologues to the other species, but now we expect functionally significant residues to have adapted to the new role of one paralogue. In order to be able to even ask such questions, we need to make the evolutionary history of gene families explicit. This is the domain of phylogenetic analysis. We can ask questions like: how many paralogues did the cenancestor of a clade possess? Which of these underwent additional duplications in the phylogenesis of the organism I am studying? Did any genes get lost? And - adding additional biological insight to the picture - did the observed duplications lead to the "invention" of new biological systems? When was that? And perhaps even: how did the species benefit from this event?

We will develop this kind of analysis in this assignment. In the previous assignment you have established which gene in your species is the reciprocally most closely related orthologue to yeast Mbp1 (with reciprocal best match) and you have identified the full complement of APSES domain genes in your assigned organism (as a result of your PSI-BLAST search). In this assignment, we will analyse these genes' evolutionary relationship and compare it to the evolutionary relationship of other fungal APSES domains. The goal is to define families of related transcription factors and their evolutionary history. I have prepared APSES domains from six diverse reference species, you will add YFO's APSES domain sequences and compute the phylogram for all genes. The goal is to identify orthologues and paralogues.

A number of excellent tools for phylogenetic analysis exist; general purpose packages include the (free) PHYLIP package, the MEGA package and the (commercial) PAUP* package. Of these, only MEGA is still under active development, although PHYLIP still functions perfectly (except for problems with graphical windows under Mac OS 10.6). Specialized tools for tree-building include Treepuzzle or Mr. Bayes. This assignment is constructed around programs that are available in PHYLIP, however you are welcome to use other tools that fulfill a similar purpose if you wish. In this field, researchers consider trees that have been built with ML (maximum likelihood) methods to be more reliable than trees that are built with parsimony methods, or distance methods such as NJ (Neighbor Joining). However ML methods are also much more compute-intensive. Just like with multiple sequence alignments, some algorithms will come closer to guessing the truth and others will not and usually it is hard to tell which is the more trustworthy of two diverging results. The prudent researcher tries out alternatives and forms her own opinion. Specifically, we may usually assume results that converge when computed with different algorithms, to be more reliable than those that depend strongly on a particular algorithm, parameters, or details of input data.

However, we will take a shortcut in this assignment (something you should not do in real life). We will skip establishing the reliability of the tree with a bootstrap procedure, i.e. repeat the tree-building a hundred times with partial data and see which branches and groupings are robust and which depend on the details of the data. (If you are interested, have a look here for the procedure for running a bootstrap analysis on the data set you are working with, but this may require a day or so of computing time on your computer.) In this assignment, we will simply acknowledge that bifurcations that are very close to each other have not been "resolved" and be appropriately cautious in our inferences. In phylogenetic analysis, not all lines a program draws are equally trustworthy. Don't take the trees as a given fact just because a program suggests this. Look at the evidence, include independent information where available, use your reasoning, and analyse the results critically. As you will see, there are some facts that we know for certain: we know which species the genes come from, and we can (usually) make good assumptions about the relationship of the species themselves - the history of speciation events that underlies all evolution of genes. This is extremely helpful information for our work.

If you would like to review concepts of trees, clades, LCAs, OTUs and the like, I have linked an excellent and very understandable introduction-level article on phylogenetic analysis here and to the resource section at the bottom of this page.

| Baldauf (2003) Phylogeny for the faint of heart: a tutorial. Trends Genet 19:345-51. (pmid: 12801728) |

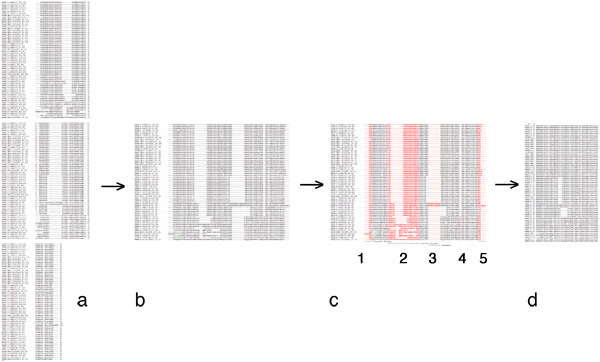

Preparing input alignments

In this section, we start from a collection of homologous APSES domains, construct a multiple sequence alignment, and edit the alignment to make it suitable for phylogenetic analysis.

Principles

In order to use molecular sequences for the construction of phylogenetic trees, you have to build a multiple alignment first, then edit it. This is important: all rows of sequences have to contain the exact same number of characters and to hold aligned characters in corresponding positions. Phylogeny programs are not meant to revise an alignment but to analyze evolutionary relationships, after the alignment has been determined. The program's inferences are made on a column-wise basis and if your columns contain data from unrelated positions, the inferences are going to be questionable. Clearly, in order for tree-estimation to work, one must not include fragments of sequence which have evolved under a different evolutionary model as all others, e.g. after domain fusion, or after accommodating large stretches of indels. Thus it is appropriate to edit the sequences and pare them down to a most characteristic subset of amino acids. The goal is not to be as comprehensive as possible, but to input those columns of aligned residues that will best represent the true phylogenetic relationships between the sequences.

The result of the tree construction is a decision about the most likely evolutionary relationships. Fundamentally, tree-construction programs decide which sequences had common ancestors.

Distance based phylogeny programs start by using sequence comparisons to estimate evolutionary distances:

- they apply a model of evolution such as a mutation data matrix, to calculate a score for each pair of sequences,

- this score is stored in a "distance matrix" ...

- ... and used to estimate a tree that groups sequences with close relationships together. (e.g. by using an NJ, Neigbor Joining, algorithm).

They are fast, can work on large numbers of sequences, but are less accurate if genes evolve at different rates.

Parsimony based phylogeny programs build a tree that minimizes the number of mutation events that are required to get from a common ancestral sequence to all observed sequences. They take all columns into account, not just a single number per sequence pair, as the Distance Methods do. For closely related sequences they work very well, but they construct inaccurate trees when they can't make good estimates for the required number of sequence changes.

ML, or Maximum Likelihood methods attempt to find the tree for which the observed sequences would be the most likely under a particular evolutionary model. They are based on a rigorous statistical framework and yield the most robust results. But they are also quite compute intensive and a tree of the size that we are building in this assignment is a challenge for the resources of common workstation (runs about an hour on my computer). If the problem is too large, one may split a large problem into smaller, obvious subtrees (e.g. analysing orthologues as a group, only including a few paralogues for comparison) and then merge the smaller trees; this way even very large problems can become tractable.

ML methods suffer less from "long-branch attraction" - the phenomenon that weakly similar sequences can be grouped inappropriately close together in a tree due to spuriously shared differences.

Bayesian methods don't estimate the tree that gives the highest likelihood for the observed data, but find the most probably tree, given that the data have been observed. If this sounds conceptually similar to you, then you are not wrong. However, the approaches employ very different algorithms. And Bayesian methods need a "prior" on trees before observation.

Choosing sequences

In principle, we have discussed strategies for using PSI-BLAST to collect suitable sequences earlier. To prepare the process, I have collected all APSES domains for six reference fungal species, together with the KilA-N domain of E. coli. The process is explained on the reference APSES domains page.

Renaming sequences

Renaming sequences so that their species is apparent is crucial for the interpretation of mixed gene trees. Refer to the reference APSES domains page to see how I have prepared the FASTA sequence headers.

Adding an outgroup

To analyse phylogenetic trees it is useful (and for some algorithms required) to define an outgroup, a sequence that presumably diverged from all other sequences in a clade before they split up among themselves. Wherever the outgroup inserts into the tree, this is the root of the rest of the tree. And whenever a molecular clock is assumed, the branching point that connects the outgroup can be assumed to be the oldest divergence event. I have defined an outgroup sequence and added it to the reference APSES domains page. The procedure is explained in detail on that page.

>gi|301025594|ref|ZP_07189117.1| KilA-N domain protein [Escherichia coli MS 69-1] MTSFQLSLISREIDGEIIHLRAKDGYINATSMCRTAGKLLSDYTRLKTTQEFFDELSRDMGIPISELIQS FKGGRPENQGTWVHPDIAINLAQWLSPKFAVQVSRWVREWMSGERTTAEMPVHLKRYMVNRSRIPHTHFS ILNELTFNLVAPLEQAGYTLPEKMVPDISQGRVFSQWLRDNRNVEPKTFPTYDHEYPDGRVYPARLYPNE YLADFKEHFNNIWLPQYAPKYFADRDKKALALIEKIMLPNLDGNEQF

E. coli KilA-N protein. Residues that do not align with APSES domains are shown in grey.

Calculating alignments

Task:

- Navigate to the reference APSES domains page and copy the APSES/KilA-N domain sequences.

- Open Jalview, select File → Input Alignment → from Textbox and paste the sequences into the textbox.

- Add the APSES domain sequences from your species (YFO) that you have previously defined through PSI-BLAST. Don't worry that the sequences are longer, the MSA algorithm should be able to take care of that. However: do rename your sequences to follow the pattern for the other domains, i.e. edit the FASTA header line to begin with the five-letter abbreviated species code.

- When all the sequences are present, click on New Window.

- In Jalview, select Web Service → Alignment → MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment. The alignment is calculated in a few minutes and displayed in a new window.

- Choose any colour scheme and add Colour → by Conservation. Adjust the slider left or right to see which columns are highly conserved.

- Save the alignment as a Jalview project before editing it for phylogenetic analysis. You may need it again.

Editing sequences

As discussed in the lecture, we should edit our alignments to make them suitable for phylogeny calculations. Here are the principles:

Follow the fundamental principle that all characters in a column should be related by homology. This implies the following rules of thumb:

- Remove all stretches of residues in which the alignment appears ambiguous (not just highly variable, but ambiguous regarding the aligned positions).

- Remove all frayed N- and C- termini, especially regions in which not all sequences that are being compared appear homologous and that may stem from unrelated domains. You want to only retain the APSES domains. All the extra residues from the YFO sequence can be deleted.

- Remove all gapped regions that appear to be alignment artefacts due to inappropriate input sequences.

- Remove all but approximately one column from gapped regions in those cases where the presence of several related insertions suggest that the indel is real, and not just an alignment artefact. (Some researchers simply remove all gapped regions).

- Remove sections N- and C- terminal of gaps where the alignment appears questionable.

- If the sequences fit on a single line you will save yourself potential trouble with block-wise vs. interleaved input. If you do run out of memory try removing columns of sequence. Or remove species that you are less interested in from the alignment.

- Move your outgroup sequence to the first line of your alignment, since this is where PHYLIP will look for it by default.

Handling indels

Gaps are a real problem, as usual. Strictly speaking, the similarity score of an alignment program as well as the distance score of a phylogeny program are not calculated for an ordered sequence, but for a sum of independent values, one for each aligned columns of characters. The order of the columns does not change the score. However in an optimal sequence alignment with gaps, this is no longer strictly true since a one-character gap creation has a different penalty score than a one-character gap extension! Most alignment programs use a model with a constant gap insertion penalty and a linear gap extension penalty. This is not rigorously justified from biology, but parametrized (or you could say "tweaked") to correspond to our observations. However, most phylogeny programs, (such as the programs in PHYLIP) do not work in this way. PHYLIP strictly operates on columns of characters and treats a gap character just like a residue with the one letter code "-". Thus gap insertion- and extension- characters get the same score. For short indels, this underestimates the distance between pairs of sequences, since any evolutionary model should reflect the fact that gaps are much less likely than point mutations. If the gap is very long though, all events are counted individually as many single substitutions (rather than one lengthy one) and this overestimates the distance. And it gets worse: long stretches of gaps can make sequences appear similar in a way that is not justified, just because they are identical in the "-" character. It is therefore common and acceptable to edit gaps in the alignment and delete all but one or two columns of gapped sequence, or to remove such columns altogether.

Task:

Prepare a PHYLIP input file from the sequences you have prepared following the principles above. The simplest way to achieve this appears to be:

- Copy the sequences you want into a textfile. Make sure the "reference sequences", are included, the outgroup and the sequences from YFO.

- In a browser, navigate to the Readseq sequence conversion service.

- Paste your sequences into the form and choose Phylip as the output format. Click on submit.

- Save the resulting page as a text file. Give it some useful name such as

APSES_domains.phy.

Calculating trees

In this section we perform the actual phylogenetic calculation.

Task:

- Download the PHYLIP package from the Phylip homepage and install it on your computer.

- Make a copy of your PHYLIP formatted sequence alignment file and name it

infile. Note: make sure that your Microsoft Windows operating system does not silently append the extension ".txt" to your file. It should be called "infile", nothing else. Place this file into the directory where the PHYLIP executables reside on your computer. - Run the proml program of PHYLIP (protein sequences, maximum likelihood tree) to calculate a phylogenetic tree (on the Mac, use proml.app). The program will automatically use "infile" for its input. Use the default parameters except that you should change option

S: Speedier but rougher analysis?toNo, not rough- your analysis should not sacrifice accuracy for speed. The calculation may take some fifteen minutes or so..

The program produces two output files: the outfile contains a summary of the run, the likelihood of bifurcations, and an ASCII representation of the tree. Open it with your usual text editor to have a look, and save the file with a meaningful name. The outtree contains the resulting tree in so-called "Newick" format. Again, have a look and save it with a meaningful filename.

Analysing your tree

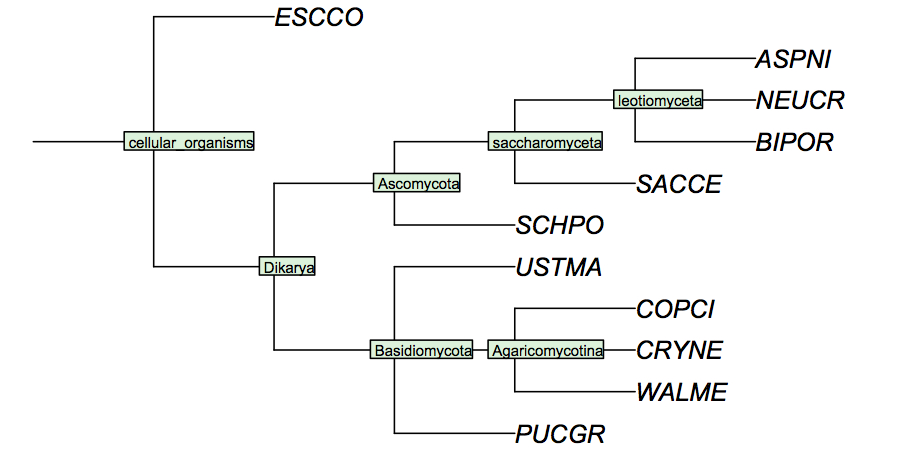

In order to analyse your tree, you need a species tree as reference. Then you can begin comparing your expectations with the observed tree.

The species tree reference

I have constructed a cladogram for many of the species we are analysing, based on data published for 1551 fungal ribosomal sequences. The six reference species are included. Such reference trees from rRNA data are a standard method of phylogenetic analysis, supported by the assumption that rRNA sequences are monophyletic and have evolved under comparable selective pressure in all species.

Your species may not be included in this cladogram, but you can easily create your own species tree with the following procedure:

Task:

- Access the NCBI taxonomy database Entrez query page.

- Edit the list of reference species below to include your species and paste it into the form.

"Aspergillus nidulans"[Scientific Name] OR "Candida albicans"[Scientific Name] OR "Neurospora crassa"[Scientific Name] OR "Saccharomyces cerevisiae"[Scientific Name] OR "Schizosaccharomyces pombe"[Scientific Name] OR "Ustilago maydis"[Scientific Name]

- Next, as Display Settings option, select Common Tree.

You can use that tree as is - or visualize it more nicely as follows

- Select the phylip tree option from the menu, and click save as to save the tree in phylip (Newick) tree format.

- The output can be edited, and visualized in any program that reads phylip trees. One particularly nice viewer is the iTOL - Interactive Tree of Life project. Copy the contents of the

phyliptree.phyfile that the NCBI page has written, navigate to the iTOL project, click on the Data Upload tab, paste your tree data and click Upload. Then go to the main display page to view the tree. Change the view from Circular to Normal.

- Alternatively ...

You can look up your species in the latest version of the species tree for the fungi:

| Ebersberger et al. (2012) A consistent phylogenetic backbone for the fungi. Mol Biol Evol 29:1319-34. (pmid: 22114356) |

Visualizing the tree

Once Phylip is done calculating the tree, the tree in a text format will be contained in the Phylip outfile - the documentation of what the program has done. Open this textfile for a first look. The tree is complicated and it can look confusing at first. The tree in Newick format is contained in the Phylip file outtree. Visualize it as follows:

Task:

- Open

outtreein a texteditor and copy the tree. - Visualize the tree in alternative representations:

- I have already mentioned the iTOL - Interactive Tree of Life project viewer.

- Navigate to the Proweb treeviewer, paste and visualize your tree.

- Navigate to the Trex-online Newick tree viewer for an alternative view. Visualize the tree as a phylogram. You can increase the window height to keep the labels from overlapping.

- A particularly useful viwer is actually Jalview.

- Open Jalview, copy the sequences you have used and paste them via File → Input Alignment → from Textbox.

- In the alignment window, choose File → Load associated Tree and load the Phylip

outtreefile. You can click into the tree-window to show which clades branch off at what level - it should be obvious that you can identify three major subclades (plus the outgroup). This view is particularly informative, since you can associate the clades of the tree with the actual sequences in the alignment, and get a good sense what sequence features the tree is based on. - Try the Calculate → Sort → By Tree Order option to sort the sequences by their position in the tree. Also note that you can flip the tree around a node by double-clicking on it. This is especially useful: try to rearrange the tree so that the subdivisions into clades are apparent. Clicking into the window "cuts" the tree and colours your sequences according to the clades in which they are found. This is useful to understand what particular sequences contributed to which part of the phylogenetic inference.

- Study the tree: understand what you see and what you would have expected.

Here are two principles that will help you make sense of the tree.

A: A gene that is present in an ancestral species is inherited in all descendant species. The gene has to be observed in all OTUs, unless its has been lost (which is a rare event).

B: Paralogous genes in an ancestral species should give rise to monophyletic subtrees for each of the paralogues, in all descendants; this means: if the LCA of a branch has e.g. three genes, we would expect three copies of the species cladogram below this branchpoint, one for each of these genes. Each of these subtrees should recapitulate the reference phylogenetic tree of the species, up to the branchpoint of their LCA.

With these two simple principles (you should draw them out on a piece of paper if they do not seem obvious to you), you can probably pry your tree apart quite nicely. A few colored pencils and a printout of the tree will help.

The APSES domains of LCA

Note: A common confusion about cenancestral genes (LCA = Last Common Ancestor) arises from the fact that by far not all expected genes are present in the OTUs. Some will have been lost, some will have been incorrectly annotated in their genome (frameshifts!) and not been found with PSI-BLAST, some may have diverged beyond recognizability. In general you have to ask: given the species represented in a subclade, what is the last common ancestor of that branch? The expectation is that all descendants of that ancestor should be represented in that branch unless one of the above reasons why a gene might be absent would apply.

Task:

- Consider how many APSES domain proteins the fungal cenancestor appears to have possessed and what evidence you see in the tree that this is so. Note that the hallmark of a clade that originated in the cenancestor is that it contains species from all subsequent major branches of the species tree.

The APSES domains of YFO

Assume that the cladogram for fungi that I have given above is correct, and that the mixed gene tree you have calculated is fundamentally correct in its overall arrangement but may have local inaccuracies due to the limited resolution of the method. You have identified the APSES domain genes of the fungal cenancestor above. Apply the expectations we have stated above to identify the sequence of duplications and/or gene loss in your organism through which YFO has ended up with the APSES domains it possesses today.

Task:

- Print the tree to a single sheet of paper.

- Mark the clades for the genes of the cenancestor.

- Label all subsequent branchpoints that affect the gene tree for YFO with either "D" (for duplication) or "S" (for speciation). Remember that specific speciation events can appear more than once in a tree. Identify such events.

- Bring this sheet with you to the quiz on Wednesday.

Bonus: when did it happen?

A very cool resource is Timetree - a tool that allows you to estimate divergence times between species. For example, the speciation event that separated the main branches of the fungi - i.e. the time when the fungal cenacestor lived - is given by the divergence time of Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Saccharomyces cerevisiaea: 761,000,000 years ago. For comparison, these two fungi are therefore approximately as related to each other as you are ...

A) to the rabbit?

B) to the opossum?

C) to the chicken?

D) to the rainbow trout?

E) to the warty sea squirt?

F) to the bumblebee?

G) to the earthworm?

H) to the fly agaric?

Check it out - the question will be on the quiz.

Identifying Orthologs

In the last assignment we discovered homologs to S. cerevisiae Mbp1 in YFO. Some of these will be orthologs to Mbp1, some will be paralogs. Some will have similar function, some will not. We discussed previously that genes that evolve under continuously similar evolutionary pressure should be most similar in sequence, and should have the most similar "function".

In this assignment we will define the YFO gene that is the most similar ortholog to S. cerevisiae Mbp1, and perform a multiple sequence alignment with it.

Let us briefly review the basic concepts.

- All related genes are homologs.

Two central definitions about the mutual relationships between related genes go back to Walter Fitch who stated them in the 1970s:

- Orthologs have diverged after speciation.

- Paralogs have diverged after duplication.

Defining orthologs

To be reasonably certain about orthology relationships, we would need to construct and analyze detailed evolutionary trees. This is computationally expensive and the results are not always unambiguous either, as we will see in a later assignment. But a number of different strategies are available that use precomputed results to define orthologs. These are especially useful for large, cross genome surveys. They are less useful for detailed analysis of individual genes. Pay the sites a visit and try a search.

- Orthologs by eggNOG

- The eggNOG (evolutionary genealogy of genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups) database contains orthologous groups of genes at the EMBL. It seems to be continuously updtaed, the search functionality is reasonable and the results for yeast Mbp1 show many genes from several fungi. Importantly, there is only one gene annotated for each species. Alignments and trees are also available, as are database downloads for algorithmic analysis.

- Orthologs at OrthoDB

- OrthoDB includes a large number of species, among them all of our protein-sequenced fungi. However the search function (by keyword) retrieves many paralogs together with the orthologs, for example, the yeast Soc2 and Phd1 proteins are found in the same orthologous group these two are clearly paralogs.

- Orthologs at OMA

OMA (the Orthologous Matrix) maintained at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology contains a large number of orthologs from sequenced genomes. Searching with MBP1_YEAST (this is the Swissprot ID) as a "Group" search finds the correct gene in EREGO, KLULA, CANGL and SACCE. But searching with the sequence of the Ustilago maydis ortholog does not find the yeast protein, but the orthologs in YARLI, SCHPO, LACCBI, CRYNE and USTMA. Apparently the orthologous group has been split into several subgroups across the fungi. However as a whole the database is carefully constructed and available for download and API access; a large and useful resource.

- Orthologs by syntenic gene order conservation

- We will revisit this when we explore the UCSC genome browser.

- Orthologs by RBM

- Defining it yourself. RBM (or: Reciprocal Best Match) is easy to compute and half of the work you have already done in Assignment 3. Get the ID for the gene which you have identified and annotated as the best BLAST match for Mbp1 in YFO and confirm that this gene has Mbp1 as the most significant hit in the yeast proteome. The results are unambiguous, but there may be residual doubt whether these two best-matching sequences are actually the most similar orthologs.

Task:

- Navigate to the BLAST homepage.

- Paste the YFO RefSeq sequence identifier into the search field. (You don't have to search with sequences–you can search directly with an NCBI identifier IF you want to search with the full-length sequence.)

- Set the database to refseq, and restrict the species to Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

- Run BLAST.

- Keep the window open for the next task.

The top hit should be yeast Mbp1 (NP_010227). E mail me your sequence identifiers if it is not. If it is, you have confirmed the RBM or BBM criterion (Reciprocal Best Match or Bidirectional Best Hit, respectively).

Technically, this is not perfectly true since you have searched with the APSES domain in one direction, with the full-length sequence in the other. For this task I wanted you to try the search-with-accession-number. Therefore the procedural laxness, I hope it is permissible. In fact, performing the reverse search with the YFO APSES domain should actually be more stringent, i.e. if you find the right gene with the longer sequence, you are even more likely to find the right gene with the shorter one.

- Orthology by annotation

- The NCBI precomputes BLAST results and makes them available at the RefSeq database entry for your protein.

Task:

- In your BLAST result page, click on the RefSeq link for your query to navigate to the RefSeq database entry for your protein.

- Follow the Blink link in the right-hand column under Related information.

- Restrict the view RefSeq under the "Display options" and to Fungi.

You should see a number of genes with low E-values and high coverage in other fungi - however this search is problematic since the full length gene across the database finds mostly Ankyrin domains.

You will find that all of these approaches yield some of the orthologs. But none finds them all. The take home message is: precomputed results are good for large-scale survey-type investigations, where you can't humanly process the information by hand. But for more detailed questions, careful manual searches are still indsipensable.

- Orthology by crowdsourcing

- Luckily a crowd of willing hands has prepared the necessary sequences for you: in the section below you will find a link to the annotated and verified Mbp1 orthologs from last year's course :-)

Links and Resources

- Literature

| Ebersberger et al. (2012) A consistent phylogenetic backbone for the fungi. Mol Biol Evol 29:1319-34. (pmid: 22114356) |

| Marcet-Houben & Gabaldón (2009) The tree versus the forest: the fungal tree of life and the topological diversity within the yeast phylome. PLoS ONE 4:e4357. (pmid: 19190756) |

| Baldauf (2003) Phylogeny for the faint of heart: a tutorial. Trends Genet 19:345-51. (pmid: 12801728) |

| Tuimala, Jarno (2006) A primer to phylogenetic analysis using the PHYLIP package. |

| (pmid: None) [ Source URL ] Abstract |

- Sequences

| Biasini et al. (2014) SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res 42:W252-8. (pmid: 24782522) |

| Bordoli & Schwede (2012) Automated protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL Workspace and the Protein Model Portal. Methods Mol Biol 857:107-36. (pmid: 22323219) |

| Peitsch (2002) About the use of protein models. Bioinformatics 18:934-8. (pmid: 12117790) |

Footnotes and references

Ask, if things don't work for you!

- If anything about the assignment is not clear to you, please ask on the mailing list. You can be certain that others will have had similar problems. Success comes from joining the conversation.

- Do consider how to ask your questions so that a meaningful answer is possible:

- How to create a Minimal, Complete, and Verifiable example on stackoverflow and ...

- How to make a great R reproducible example are required reading.

| < Assignment 7 | Assignment 9 > |