Difference between revisions of "User:Boris/Temp/APB"

| Line 332: | Line 332: | ||

<div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| − | + | (1.2) Input for APSES domain sequences (1 mark) | |

</div> | </div> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 04:30, 10 October 2007

Note! This assignment is currently inactive. Major and minor unannounced changes may be made at any time.

Contents

Assignment 3 - Multiple Sequence Alignment

Please note: This assignment is currently inactive. Unannounced changes may be made at any time.

Introduction

- Take care of things, and they will take care of you.

- Shunryu Suzuki

A carefully done multiple sequence alignment (MSA) is a cornerstone for the annotation of a gene or protein. MSAs combine the information from several related proteins, allowing us to study their essential, shared and conserved properties. They are useful to resolve ambiguities in the precise placement of gaps and to ensure that columns in alignments actually contain amino acids that evolve in a similar context. Therefore we need MSAs as input for

- protein homology modeling,

- phylogenetic analyses, and

- sensitive homology searches in databases.

In addition, conservation - or the lack of conservation - is a consequence of selection under the constraints imposed by the structural or functional features of a protein. Conservation patterns emphasize domain boundaries in multi-domain proteins, and amino acid propensities are powerful predictors for protein engineering and design.

Given the ubiquitous importance of multiple sequence alignment, it is remarkable that by far the most frequently used algorithm is CLUSTAL, a procedure that was first published for the microprocessors of the late 1980s, surpassed in performance many times and shown to be significantly inferior to more modern approaches for sequences with about 30% identity or less.

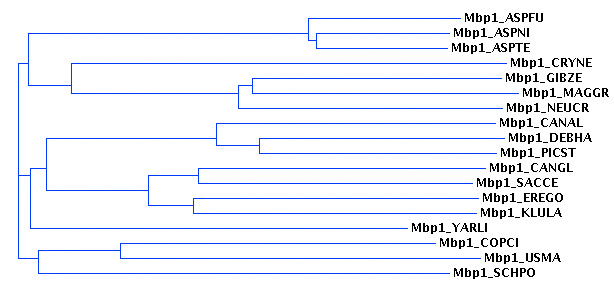

In this assignment we will explore MSAs of fungal proteins that are orthologous to yeast Mbp1, and of the APSES domains they contain, and compare several approaches to alignment:

- A model-based approach (based on the PSSM that PSI-BLAST generates)

- A progressive alignment - the CLUSTAL algorithm

- A consistency based alignment - T-Coffee, MUSCLE or Probcons

Preparation, submission and due date

Please read carefully. Be sure you have understood all parts of the assignment and cover all questions in your answers! Sadly, we always get assignments back in which people have simply overlooked crucial questions. Sadly, we always get assignments back in which people have not described procedural details. If you did not notice that the above were two different sentences, you are still not reading carefully enough.

Prepare a Microsoft Word document with a title page that contains:

- your full name

- your Student ID

- your e-mail address

- the organism name you have been assigned

Follow the steps outlined below. You are encouraged to write your answers in short answer form or point form, like you would document an analysis in a laboratory notebook. However, you must

- document what you have done,

- note what Web sites and tools you have used,

- paste important data sequences, alignments, information etc.

If you do not document the process of your work, we will deduct marks. Try to be concise, not wordy! Use your judgement: are you giving us enough information so we could exactly reproduce what you have done? If not, we will deduct marks. Avoid RTF and unnecessary formating. Do not paste screendumps or other uncompressed images. The size of your submission must remain below 1.5 MB.

Write your answers into separate paragraphs and give each its title. Save your document with a filename of:

A3_family name.given name.doc

(for example my submission would be named: A3_steipe.boris.doc - and don't switch the order of your given name and family name please!)

Finally e-mail the document to boris.steipe@utoronto.ca before the due date.

Your document must not contain macros. Please turn off and/or remove all macros from your Word document; we will disable macros, since they pose a security risk.

With the number of students in the course, we have to economize on processing the assignments. Thus we will not accept assignments that are not prepared as described above. If you have technical difficulties, contact the course coordinator.

The due date for the assignment is Monday, October 22. at 10:00.

Grading

Don't wait until the last day to find out there are problems! Assignments that are received past the due date will have one mark deducted and an additional mark for every full twelve hour period past the due date. Assignments received more than 5 days past the due date will not be assessed. If you need an extension, you must arrange this beforehand.

Marks are noted below in the section headings for of the tasks. A total of 10 marks will be awarded, if your assignment answers all of the questions. A total of 2 bonus marks (up to a maximum of 10 overall) can be awarded for particularily interesting findings, or insightful comments. A total of 2 marks can be subtracted for lack of form or for glaring errors. The marks you receive will

- count directly towards your final marks at the end of term, for BCH441 (undergraduates), or

- be divided by two for BCH1441 (graduates).

(1) Retrieve

In Assignment 2 you retrieved the protein sequences of saccharomyces cerevisiae Mbp1 and its orthologue in your assigned organism. In order to produce a multiple sequence alignment, we have to define which sequences we wish to use. Then we need to retrieve the sequences from the database. Finally we have to store the sequences in a format that we can use as input for the alignment programs.

(1.1) Input for Mbp1 orthologues (1 mark)

In your second assignments, you used BLAST to find the best matches to the yeast Mbp1 protein in your assigned organism's genome. To avoid ambiguity, I have generated a reference list of these homologues using the canonical procedure defined below. Note that several departures from the procedure were necessary, as explained below the table; I consider these variations quite normal for a database query. You need to be familiar with such exceptions and how to deal with them.

- Retrieved the Mbp1 protein sequence by searching Entrez for

Mbp1 AND "saccharomyces cerevisiae"[organism] - Clicked on the RefSeq tab to find the RefSeq ID "

NP_010227" - Accessed the BLAST form, followed the link to the list of all genomic BLAST databases and clicked on the (B) icon, next to Fungi to navigate to the Fungi Genomic BLAST page.

- Pasted "

NP_010227" into the query field. Chose Protein for both Query and Database, kept default parameters but set the Filter option to none. Clicked on the check-box of each of the fungal species we have considered in the previous assignment. Run BLAST. - On the results page, checked the checkbox next to the alignment to select the most significant hit from each organism' we are studying.

- Clicked on the "Get selected sequences" button.

- Separately searched for sequences from organisms that were either not included in the lsit or for which no hits were reported. Verified all ambiguous cases, as explained in the notes below.

- Verified that each of these sequences finds Mbp1 as the best match in the saccharomyces cerevisiae genome by clicking on each "BLink" (click for example) in the retrieved list. Scrolled down the list to confirm that the top hit of a saccharomyces cerevisiae protein is indeed Mbp1 (

NP_010227). - Obtained UniProt accessions for all sequences, with a single query using the UniProt ID mapping service. This service accepts a comma delimited list of RefSeq IDs, GI numbers or GenPept accession numbers and returns a list of Uniprot accession numbers.

Since it was thus confirmed that each of these sequences is the protein that is most similar to yeast Mbp1 in its respective organism's genome, and that yeast Mbp1 is the most similar yeast protein to each of them, the all fulfil the criterion of a reciprocal best match with yeast Mbp1. Accordingly we can postulate that this list contains the fungal orthologues to Mbp1.

| Mbp1 and its orthologues | |||||

| Organism | CODE |

GI | NCBI | Uniprot | Most similar yeast gene |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | ASPFU |

70986922 | XP_748947 | Q4WGN2_ASPFU | Mbp1 |

| Aspergillus nidulans | ASPNI |

40739343 | EAA58533 | Q5AYB5_EMENI | Mbp1 |

| Aspergillus terreus | ASPTE |

115391425 | XP_001213217 | Q0CQJ5_ASPTN | Mbp1 |

| Candida albicans | CANAL |

46444933 | EAL04204 | Q5ANP5_CANAL | Mbp1 |

| Candida glabrata | CANGL |

50286059 | XP_445458 | Q6FWD6_CANGA | Mbp1 |

| Coprinopsis cinerea | COPCI |

116501415 | EAU84310 | N.A. | Mbp1 |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | CRYNE |

134110416 | XP_776035 | Q5KHS0_CRYNE | Mbp1 |

| Debaryomyces hansenii | DEBHA |

50420495 | XP_458784 | Q6BSN6_DEBHA | Mbp1 |

| Eremothecium gossypii | EREGO |

45199118 | NP_986147 | Q752H3_ASHGO | Mbp1 |

| Gibberella zeae | GIBZE |

46116756 | XP_384396 | UPI000023DBF3 | Mbp1 |

| Kluyveromyces lactis | KLULA |

50308375 | XP_454189 | MBP1_KLULA | Mbp1 |

| Magnaporthe grisea | MAGGR |

74274844 | ABA02072 | Q3S405_MAGGR | Mbp1* |

| Neurospora crassa | NEUCR |

157070373 | EAA33731 | Q7SBG9 | Mbp1 |

| Pichia stipitis | PICST |

149388844 | EAZ62798 | A3GHD6_PICST | Mbp1 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | SACCE |

6320147 | NP_010227 | MBP1_YEAST | Mbp1 |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | SCHPO |

19113944 | NP_593032 | RES2_SCHPO | Mbp1 |

| Ustilago maydis | USTMA |

46101867 | EAK87100 | Q4P117_USTMA | Mbp1 |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | YARLI |

50545439 | XP_500257 | Q6CGF5_YARLI | Mbp1 |

Table of yeast Mbp1 orthologues in genome-sequenced fungi. Columns from left to right: Systematic name, organism code (simply a string that lets us identify the organism in alignments), GI number, RefSeq ID (if existing) or GenPept accession, Uniprot accession, most similar yeast protein.

Note: Coprinopsis cinerea accession numbers are not yet in UniProt.

Note: For Giberella zeae and Magnaporthe grisea, the protein BLAST search had to go through the entire nr database, by entering an organism restriction, since genomic BLAST was not enabled.

Note: For Giberella zeae XP_384396 no UniProt ID was returned as cross-reference. EBI-BLAST retrieved FG04220 which is largely identical, except for short stretches that are absent in GenPept: apparently UniProt has a different gene-model for this protein.

Note: The Neurospora crassa protein EAA33731 has no direct cross-reference in UniProt. The closest match is Q7SBG9 which is largely identical, except for short stretches that are absent in GenPept: apparently UniProt has a different gene-model for this protein.

Note: The Magnaporthe grisea protein ABA02072 has greater local C-terminal similarity to the yeast protein Swi6 than to Mbp1, whereas the N-terminal APSES domain is most similar to yeast Mbp1. However a global Needleman-Wunsch alignment (BLOSUM 30, gaps: 8.0/1.0) shows greater overall similarity to yeast Mbp1 than to Swi6. Accordingly I consider this an orthologue to Mbp1 even though its database annotation calls ABA02072 the M. grisea Swi6 homologue.

Note: For Pichia stipitis, BLAST finds two very similar sequences in GenPept as candidate Mbp1 orthologues; the RefSeq sequence XP_001386821.1 is translated according to the standard code, the EMBL generated entry EAZ62798.2 is translated according to the alternative nuclear code 12. The question had to be considered which translation appears to be correct. This requires looking at the conservation of the residues in question in the BAST alignment.

Note: The Ustilago maydis protein EAK87100 is only the second-best hit in the original BLAST list, however local optimal alignment (EMBOSS water) shows a much higher percentage of identity to yeast Mbp1 in the APSES domain than the top BLAST hit EAK86587 and global alignment (after trimming the N- and C- terminal extensions, respsectively) also shows a slightly higher degree of similarity for EAK87100 than EAK86587. Accordingly, EAK87100 is considered the Mbp1 orthologue, even though it is the second highest hit according to BLAST. This emphasizes the fact that optimal sequence alignments are not entirely equivalent to BLAST alignments.

Our second task is to obtain all FASTA sequences based on a list of identifiers and to save them in a format in which we can use them as input for other programs or services. This is easy: we simply paset all GI numbers as a comma separated list into the Entrez search form and select Display FASTA, send to Text on the results page, then save the contents as a Text file.

- We have applied the "reciprocal best match criterion" to assert that these sequences are orthologues to yeast Mbp1 and this is how orthologues are commonly defined comnputationally. Briefly explain why this criterium will distinguish between orthologues and paralogues (when no genes have been lost). Consider at least the following three cases (i) a gene duplication has occurred before a speciation event, (ii) a gene duplication in the query organism has occurred after a speciation event. (iii) a gene duplication in the target organism has occurred after a speciation event. Use sketches to illustrate the cases.

- Review the resulting multi-FASTA file for the Mbp1 proteins (linked here) and make sure you understand the procedure that led to it. Depending on your personal learning style you may either carefully review the described procedure, reproduce key steps of the procedure, reproduce the entire procedure paying special attention to the problem cases discussed in the notes, or develop your own procedure. Whatever you do, you must be confident in the end that you could have produced the same input file. (1 mark)

(1.2) Input for APSES domain sequences (1 mark)

Mbp1 orthologues are not the only proteins that contain APSES domains. In order to find all the rest, a PSI BLAST search was performed using the yeast Mbp1 APSES domain as query. From the list of hits, the APSES domains were extracted and summarized in a file.

- Review the resulting file for the APSES domains and make sure you understand the procedure that led to it. Summarize the key steps of the procedure in point form. (1 mark)

(1.2) Orthologues (1 mark)

For one of the the APSES domains from your assigned organism, determine whether it is orthologous to a yeast APSES domain:

- Choose at random one of the APSES domains from your organism (but not one from an Mbp1 orthologue) and copy it's sequence into the input window of a genomic BLAST search against saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins.

- Run the search and determine the gene name of the best hit. (This is the best match.)

- The BLAST-retrieved sequence may be truncated on the results page.

- Find the sequence of your best match in yeast in the sequence file. (Since the file contains all yeast APSES domains, your best match should be in this file, labeled with

????_SACCE. - Copy that sequence and perform the same kind of BLAST search with this yeast sequence, against the proteins in your oranism's genome. (This finds the reciprocal match.)

- Document the process and report briefly what you have found on the forward and on the reverse search. Does the gene you have chosen fulfill the reciprocal best match criterium for orthology with a yeast gene? (1 mark)

(2) Align

Actually performing multiple sequence alignements used to involve downloading and installing software on your own computer. While most tools were available on the Web in principle, many groups have restricted the total number of sequences or the total number of characters to be aligned. The EBI however offers three of the most commonly used tools with few limitations and it was possible to run MSAs for all Mbp1 orthologues jointly.

(2.1) Aligning the Mbp1 orthologues (1 mark)

I used the following three servers:

- CLUSTAL-W is a progressive alignment program, it is the most popular, most widely referenced MSA algorithm, it is reasonably fast and easy to use. But alignment errors that are made early can't get corrected and thus it is prone to misalignments on sets of sequences that have poor (<30% ID) local similarity. It is no longer considered state-of-the-art for carefully done alignments.

- MUSCLE essentially starts out from a CLUSTAL like alignment as a draft, then identifies similar groups of sequences from which it calculates profiles, it then re-aligns the group to the profile. This procedure is iterated.

- T-Coffee is one of my favourites - the tradeoffs appear to be especially well balanced. It too starts from a set of pairwise global alignments, like CLUSTAL, then additionally calculates sets of best local alignments. Global and local alignments are then combined to a similarity matrix and based on this matrix a guide-tree is constructed. This determines the order of steps in which sequences are added to the multiple alignment. A nice feature of T-Coffee is color coded output that allows you to quickly judge the local reliability of the alignment.

We shall perform multiple sequence alignments for all 16 Mbp1 orthologues and compare the results. Since the results should look the same for all of you, it was possible to precompute the alignments to save some resources. Of course you are welcome to do this on your own, but it is not required. In fact, since we want to compare the alignments, I have also edited them: I have re-sorted the results so that the sequences appear in the same order in each case. Only CLUSTAL provides the option to order the output in the same way as the input, the other two programs order the output so that adjacent sequences are most similar. This is useful, because it emphasizes sequence features, but it makes it impossibly tedious to compare alignments.

The result files are linked here:

- Mbp1 proteins CLUSTAL aligned

- Mbp1 proteins MUSCLE aligned

- Mbp1 proteins T-Coffee aligned (text version) and (coloured according to scores)

Globally speaking, the alignments are quite similar. Let's first look at the common themes, before we discuss details of the results. The (score-colored T-COFFEE alignment) is well suited to look at general relationships between the sequences, since outliers can be easily identified. For example, if one of the sequences would have a low-scoring domain, aligning poorly to the others of the group, it may be possible that that domain has been acquired in a separate evolutionary event and is not homologous to all others. We would notice an isolated stretch of poorly alignable sequence, i.e. it should be coloured wihth a low score in a set of otherwise high-scoring segments. Also a gene may have acquired significant lengths of N- or C-terminal extensions which may not be homologous (unless they are the reuslt of an internal duplication).

- Review the (score-colored T-Coffee alignment). Based on this alignment, how do you feel about our initial assertion that these proteins should be considered orthologous? (Answer briefly, but with reference to specific evidence in the alignment. Note that this is not about the general level of conservation, but about whether significant segments do not appear related/alignable at all.) (1 mark)

(3) Mbp1 orthologues: analysis of full length MSAs

What do we mean by a good versus a poor multiple sequence alignment?

Let us first consider some of the features we have defined in the second assignment (and some structural features I have added). Here is an annotation of the yeast Mbp1 sequence. It was compiled with the following procedure.

- Performed CDD search with yeast Mbp1 protein sequence. This retrieves alignments of Mbp1 with the APSES and the ANKYRIN domains. These are profile based alignment and I would consider them more reliable than pairwise alignments.

- Performed SMART search with yeast Mbp1 protein sequence. This retrieved the APSES domain, annotated a number of low-complexity regions and a stretch of coiled coil.

- Performed a SAS search with yeast Mbp1 protein sequence. This retrieved pairwise alignments with the structures 1MB1 (APSES) and chain D of 1IKN (ankyrin domains of Ikappab), together with their respectve secondary structure annotations.

- Copied GenPept sequence into Word-processor.

- Transferred annotations of low complexity and coiled-coil regions from SMART.

- Transferred annotations of APSES seondary structure from SAS (this is a direct annotation, since the structure 1MB1 has the same sequence as the coressponding parts of the Mbp1 protein). The central helix of the binding region is slightly distorted and SAS annotates a break in the helix, this was bridged with lowercase "h" in the annotation.

- Ankyrin domain annotation was not as straightforward. While CDD, SMART and SAS all annotate the same general regions, they disagree in details of the domain boundaries and in the precise alignment. Used the profile-based CDD alignment of 1IKN. Transferred annotations of secondary structure from SAS output for 1IKN to sequence (this is a transferred annotation, the original annotation was for 1IKN and we assume that it applies to Mbp1 as well).

MBP1_SACCE

Annotations based on

- CDD domain analysis,

- SAS structure annotation and

- literature data on binding region

Keys:

C Coiled coil regions predicted by Coils2 program

x Low complexity region

* Proposed binding region

+ positively charged residues, oriented for possible DNA binding interactions

- negatively charged residues, oriented for possible DNA binding interactions

E beta strand

H alpha helix

t beta turn

10 20 30 40 50 60

MSNQIYSARY SGVDVYEFIH STGSIMKRKK DDWVNATHIL KAANFAKAKR TRILEKEVLK

1MB1 ----EEEEEt t-EEEEEEEE t-EEEEEEtt ---EEHHHHH HH----HHHH HHHHhhhHHH

* *+**-+****

70 80 90 100 110 120

ETHEKVQGGF GKYQGTWVPL NIAKQLAEKF SVYDQLKPLF DFTQTDGSAS PPPAPKHHHA

1MB1 ---EEE---- tt--EEEE-H HHHHHHHHH- --HHHHtt- xxx xxxxxxxxxx

**+*+***** ****

130 140 150 160 170 180

SKVDRKKAIR SASTSAIMET KRNNKKAEEN QFQSSKILGN PTAAPRKRGR PVGSTRGSRR

x

190 200 210 220 230 240

KLGVNLQRSQ SDMGFPRPAI PNSSISTTQL PSIRSTMGPQ SPTLGILEEE RHDSRQQQPQ

xxxxx

250 260 270 280 290 300

QNNSAQFKEI DLEDGLSSDV EPSQQLQQVF NQNTGFVPQQ QSSLIQTQQT ESMATSVSSS

x xx xxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxx

310 320 330 340 350 360

PSLPTSPGDF ADSNPFEERF PGGGTSPIIS MIPRYPVTSR PQTSDINDKV NKYLSKLVDY

xxxxxxx

370 380 390 400 410 420

FISNEMKSNK SLPQVLLHPP PHSAPYIDAP IDPELHTAFH WACSMGNLPI AEALYEAGTS

ANKYRIN -- t----HHHHH HH---HHHHH t-t--t-t--

430 440 450 460 470 480

IRSTNSQGQT PLMRSSLFHN SYTRRTFPRI FQLLHETVFD IDSQSQTVIH HIVKRKSTTP

ANKYRIN t----t---- HHHHHHHH-- -------HHH HHHHHH-ttH HH-----HHH HHHH--tH--

490 500 510 520 530 540

SAVYYLDVVL SKIKDFSPQY RIELLLNTQD KNGDTALHIA SKNGDVVFFN TLVKMGALTT

ANKYRIN HHHHHHHHH- ---------- -----t---- tt---HHHHH HH---HHHHH HHH--t-tt-

550 560 570 580 590 600

ISNKEGLTAN EIMNQQYEQM MIQNGTNQHV NSSNTDLNIH VNTNNIETKN DVNSMVIMSP

ANKYRIN ---t----HH HHHHHH--HH HHH-t--HHH -t----HHHH HHH--tHHHH HHHHHH---t

610 620 630 640 650 660

VSPSDYITYP SQIATNISRN IPNVVNSMKQ MASIYNDLHE QHDNEIKSLQ KTLKSISKTK

ANKYRIN ---tt----H HHHHHH---H HHHHHHH CCCCCCCC CCCCCCCCCC CCCCC

670 680 690 700 710 720

IQVSLKTLEV LKESSKDENG EAQTNDDFEI LSRLQEQNTK KLRKRLIRYK RLIKQKLEYR

x xxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxx

730 740 750 760 770 780

QTVLLNKLIE DETQATTNNT VEKDNNTLER LELAQELTML QLQRKNKLSS LVKKFEDNAK

790 800 810 820 830

IHKYRRIIRE GTEMNIEEVD SSLDVILQTL IANNNKNKGA EQIITISNAN SHA

A good MSA comprises only columns of residues that play similar roles in the proteins' mechanism and/or that evolve in a comparable structural context. Since it is a result of biological selection and conservation, it has relatively few indels and the indels it has are usually not placed into elements of secondary structure or into functional motifs.

A poor MSA has many errors in its columns in the sense that they contain residues that actuallly have diffferent functions or structural roles, even though they may look similar to a scoring matrix. It also may have introduced indels in biologically irrelevant positions, to maximize spurious sequence similarities.

In order to evaluate the MSAs for our proteins, we will analyze alignments relative to the features we have annotated above.

(3.1) APSES domains (1 mark)

The APSES domains in all of our Mbp1 orthologues are highly conserved and a program that would misalign such obvius similarity would not be worth the electrons it computes with.

- Consider the CLUSTAL, Muscle and T-Coffee alignments of the Mbp1 orthologues. Orient yourselves as to where the APSES domains are located. Briefly note whether the three alignments agree and whether the charged residues in the proposed binding region are wholly or partially conserved. (Refer to the specific residues labelled (+) or (-) in the Mbp1 annotation above). (1 mark)

(3.2) Ankyrin domains (1 mark)

The Ankyrin domains are more highly diverged, the boundaries are less well defined and not even CDD, SMART and SAS agree on the precise annotations. Nevertheless we would hope that a good alignment would recognize homology in that region and that ideally the required indels would be placed between the secondary structure elements, not in their middle.

- For one of the alignments of your choice, identify the helices in the Ankyrin repeat region of Mbp1. To facilitate this, I have colored the annotated ankyrin helices red in the yeast Mbp1 protein. Briefly state whether the indels are concentrated in regions that connect the helices or if they are more or less evenly distributed along the entire region of similarity. Conclude whether the assertion that indels should not be placed in elelements of secondary structure has merit in this case, i.e. whether the indels that violate it have strong support from aligned sequence motifs. (1 mark)

(3.3) Other features (2 marks)

Aligning functional features like coiled coil domains or intrinsically disorderd regions is even more difficult, since this is to a large degree a property of the amino acid composition, not as much the precise sequence. Thus we would expect alignment algorithms to have difficulty to detect the correspondence between sequences in such regions. I have marked the four low complexity regions of the yeast Mbp1 sequence with bold letters in all three alignments.

- Copy the Mbp1 sequence from your organism from the multi-FASTA files and run a SMART sequence analysis: paste your sequence (or the Uniprot accession number), check only the checkbox for detecting intrinsic protein disorder and click "Sequence SMART". Locate the segments of low complexity for your sequence (they are in the lower part of the results page since they overlap with disordered segements). Find the corresponding positions for your sequence in one of the multiple sequence alignments. Briefly describe the situation: state whether these segments are found in the same general region, in the same detailed location, or perhaps even conserved in sequence, when you compare them to the saccharomyces cerevisiae sequence. (1 mark)

- Briefly discuss whether this observation should lead you to conclude that disorder in these proteins appears to be a conserved feature, i.e. that is selected for in evolution. (1 mark)

(4) APSES domain homologues: analysis of domain MSAs

The procedures for obtaining the MSAs for all APSES domains is summarized at the top of the page for each alignment. Read it and make sure you understand what has been done. Three approaches were used:

- An alignment based on the PSI-BLAST reults as an example of a profile-based alignment.

- A CLUSTAL-W alignment as an example of our standard, plain vanilla progressive alignment procedure.

- A consistency based, iterated alignment using probcons, as an example of the more modern methods. probcons was used rather than T-Coffee since the EBI server restricts the number of sequences it will accept to 50.

Comparing the three alignments, we note that they do not agree in detail over large stretches.

(4.1) Manual improvement (1 mark)

Often errors or inconsistencies are easy to spot and manually editing an MSA is not generally frowned upon, even though this is not a strictly objective procedure. The main goal is to make an alignment biologically more plausible, usually this means to mimize the number of rare events that we need to postulate for the alignment: move indels into more appropriate positions and/or to emphasize conservation of known functional motifs. Here are some examples for what one might aim for in manually editing an alignment:

- Reduce number of indels

From Probcons: 0447_DEBHA ILKTE-K-T---K--SVVK ILKTE----KTK---SVVK 9978_GIBZE MLGLN-PGLKEIT--HSIT MLGLNPGLKEIT---HSIT 1513_CANAL ILKTE-K-I---K--NVVK ILKTE----KIK---NVVK 6132_SCHPO ELDDI-I-ESGDY--ENVD ELDDI-IESGDY---ENVD 1244_ASPFU ----N-PGLREIC--HSIT -> ----NPGLREIC---HSIT 0925_USTMA LVKTC-PALDPHI--TKLK LVKTCPALDPHI---TKLK 2599_ASPTE VLDAN-PGLREIS--HSIT VLDANPGLREIS---HSIT 9773_DEBHA LLESTPKQYHQHI--KRIR LLESTPKQYHQHI--KRIR 0918_CANAL LLESTPKEYQQYI--KRIR LLESTPKEYQQYI--KRIR

Gaps marked in red were moved. The sequence similarity in the alignment does not change considerably, however the total number of indels in this excerpt is reduced to 13 from the original 22

- Move indels to more plausible position

From CLUSTAL: 4966_CANGL MKHEKVQ------GGYGRFQ---GTW MKHEKVQ------GGYGRFQ---GTW 1513_CANAL KIKNVVK------VGSMNLK---GVW KIKNVVK------VGSMNLK---GVW 6132_SCHPO VDSKHP-----------QID---GVW -> VDSKHPQ-----------ID---GVW 1244_ASPFU EICHSIT------GGALAAQ---GYW EICHSIT------GGALAAQ---GYW

The two characters marked in red were swapped. This does not change the number of indels but places the "Q" into a a column in which it is more highly conserved (green). Progressive alignments are especially prone to this type of error.

- Conserve motifs

From CLUSTAL: 6166_SCHPO --DKRVA---GLWVPP --DKRVA--G-LWVPP XBP1_SACCE GGYIKIQ---GTWLPM GGYIKIQ--G-TWLPM 6355_ASPTE --DEIAG---NVWISP -> ---DEIA--GNVWISP 5262_KLULA GGYIKIQ---GTWLPY GGYIKIQ--G-TWLPY

The first of the two residues marked in red is a conserved, solvent exposed hydrophobic residue that may mediate domain interactions. The second residue is the conserved glycine in a beta turn that cannot be mutated without structural disruption. Changing the position of a gap and insertion in one sequence improves the conservation of both motifs.

Please consider the following excerpts from the alignments:

PSI-BLAST MBP1_SACCE SIMKRKKDDWVNATHILKA------A----------NFA--------KAKRTR----- 2599_ASPTE -IMWDYNIGLVRTTPLFRS------Q----------NYS--------KTTPAK----- 9773_DEBHA -IIWDYETGFVHLTGIWKA------S----------INDEVNTHRNLKADIVK----- 0918_CANAL -VIWDYETGWVHLTGIWKA------SLTIDGSNVSPSHL--------KADIVK----- 9901_DEBHA -ILRRVQDSYINISQLF--------SILLKIG----HLS--------EAQLTN----- 7766_ASPNI -LMRRSKDGYVSATGMFKI------A-----------FP--------WAKLEEERSER 5459_GIBZE -LMRRSYDGFVSATGMFKASFPYAEA----------SDE--------DAERKY----- 2267_NEUCR -LMRRSQDGYISATGMFKA------TFPYASQ----EEE--------EAERKY----- 3510_ASPFU -LMRRSKDGYVSATGMFKI------A-----------FP--------WAK-------- 3762_MAGGR -LMRRSSDGYVSATGMFKATFPYADA----------EDE--------EAERNY----- 3412_CANAL -VLRRVQDSFVNVTQLFQI------LIKLE------VLP--------TSQVDN-----

CLUSTAL MBP1_SACCE SIMKRKKDDWVNATHILKAAN----------FAKAKRTRILE----------KEVLKETHE 2599_ASPTE -IMWDYNIGLVRTTPLFRSQ----------NYSKTTPAKVLDAN--------P-GLREISH 9773_DEBHA -IIWDYETGFVHLTGIWKASIN-DEVNTHR-NLKADIVKLLEST--------PKQYHQHIK 0918_CANAL -VIWDYETGWVHLTGIWKASLTIDGSNVSPSHLKADIVKLLEST--------PKEYQQYIK 9901_DEBHA -ILRRVQDSYINISQLFSILL----------KIGHLSEAQLTNFLNNEILTNTQYLSSGGS 7766_ASPNI -LMRRSKDGYVSATGMFKIAF----------PWAKLEEERSE----------REYLKTRPE 5459_GIBZE -LMRRSYDGFVSATGMFKASF----------PYAEASDEDAE----------RKYIKSLPT 2267_NEUCR -LMRRSQDGYISATGMFKATF----------PYASQEEEEAE----------RKYIKSIPT 3510_ASPFU -LMRRSKDGYVSATGMFKIAF----------PWAKLEEEKAE----------REYLKTREG 3762_MAGGR -LMRRSSDGYVSATGMFKATF----------PYADAEDEEAE----------RNYIKSLPA 3412_CANAL -VLRRVQDSFVNVTQLFQILI----------KLEVLPTSQVDNYFDNEILSNLKYFGSSSN

Probcons MBP1_SACCE SIMKRKKDDWVNATHILKAANF----AKA----------KRTRILEKE-V-LKETH--E 2599_ASPTE -IMWDYNIGLVRTTPLFRSQNY----SKT----------TPAKVLDAN-PGLREIS--H 9773_DEBHA -IIWDYETGFVHLTGIWKASIN----DEV--NTHRNLKADIVKLLESTPKQYHQHI--K 0918_CANAL -VIWDYETGWVHLTGIWKASLT----IDGSNVSPSHLKADIVKLLESTPKEYQQYI--K 9901_DEBHA -ILRRVQDSYINISQLFSILLKIGHLSEA----------QLTNFLNNE-I-LTNTQYLS 7766_ASPNI -LMRRSKDGYVSATGMFKIAFP----WAK----------LEEERSERE-Y-LK-----T 5459_GIBZE -LMRRSYDGFVSATGMFKASFP----YAE----------ASDEDAERK-Y-IK-----S 2267_NEUCR -LMRRSQDGYISATGMFKATFP----YAS----------QEEEEAERK-Y-IK-----S 3510_ASPFU -LMRRSKDGYVSATGMFKIAFP----WAK----------LEEEKAERE-Y-LK-----T 3762_MAGGR -LMRRSSDGYVSATGMFKATFP----YAD----------AEDEEAERN-Y-IK-----S 3412_CANAL -VLRRVQDSFVNVTQLFQILIKLEVLPTS----------QVDNYFDNE-I-LSNLKYFG

- In any one of these excerpts, find at least one example where the alignment could be manually improved. Show the original version, the improved version and highlight the changes in red. (1 mark)

The fact that such improvements usually are not hard to find teaches us to be cautious with the results. Not in all cases will lack of conservation in a particular column mean that a residue has changed in evolution - sometimes this is simply a consequence of misalignment. MSAs can only take sequence information into account, while we may have additional information on structural and functional conservation patterns. This may include secondary structure (gaps should be moved out of regions of secondary structure, where possible), structurally required residues (expected to be conserved accross all structurally similar sequences) and functionally conserved residues (expected to have a high likelyhood of being conserved within groups of orthologues, but varying between orthologues and paralogues).

In terms of structural conservation, we expect motif or consistency based alignments to be more accurate since they align to the "big picture". In terms of functional variation we expect progressive alignments to be more accurate, since they align to local similarities.

(4.2) Residue conservation (1 mark)

Let us finally interpret the alignments in terms of their biological relevance. I have transferred the ligand-binding annotations for the yeast Mbp1 APSES domain into the multiple sequence alignments by color coding the charged residues that putatively could bind DNA red (-) and blue (+). Thus these residues label columns in which we expect functional conservation. I have labeled two residues that are associated with important structural features green. These two residues are G75, a mandatory glycine in the third position of a particular type of beta-turn, and W77, a key component of the domain's hydrophobic core. Thus these two residues label columns in which we expect structural conservation. Let's assume that all the APSES domains fold into similar structures and that they all bind DNA, although not necessarily the same cognate sequence. This should allow you to answer the following questions:

Consider any one of the three APSES domain MSAs.

- Are the patterns of sequence variation for functionally conserved residues compatible with different binding specificities for different APSES domains? State briefly (but with reference to specific residues) what you would expect and what you find.

- Are the patterns of sequence variation for structurally conserved residues compatible with a common fold of different APSES domains? State briefly (but with reference to specific residues) what you would expect and what you find. (1 mark)

(5) Summary of Resources

- Links

- Sequences

- Alignments

- Mbp1 proteins:

- APSES domains:

[End of assignment]

If you have any questions at all, don't hesitate to mail me at boris.steipe@utoronto.ca or post your question to the Course Mailing List