Difference between revisions of "BIO Assignment 5 2011"

m |

|||

| (19 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Template:Inactive}} | + | <!-- {{Template:Inactive}} --> |

| − | + | {{Template:Active}} | |

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

<div style="padding: 5px; background: #A6AFD0; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA; font-size:200%;font-weight:bold;"> | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #A6AFD0; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA; font-size:200%;font-weight:bold;"> | ||

| − | Assignment 5 - | + | Assignment 5 (last: 2011) - Homology modeling |

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <div style="padding: | + | <div style="padding: 15px; background: #F0F1F7; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA; font-size:125%;color:#444444"> |

| − | + | ;How could the search for ultimate truth have revealed so hideous and visceral-looking an object? | |

| + | ::''<small>Max Perutz (on his first glimpse of the Hemoglobin structure)</small>'' | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | | ||

| | ||

| − | + | Where is the hidden beauty in structure, and where, the "ultimate truth"? In the previous assignments we have studied sequence conservation in APSES family domains and we have discovered homologues in all fungal species. This is an ancient protein family that had already duplicated to several paralogues at the time the cenancestor of all fungi lived, more than 600,000,000 years ago, in the [http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/fungi/fungifr.html Vendian period] of the Proterozoic era of Precambrian times. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ... | + | In order to understand how specific residues in the sequence contribute to the putative function of the protein, and why and how they are conserved throughout evolution, we would need to study an explicit molecular model of an APSES domain protein, bound to its cognate DNA sequence. Explanations of a protein's observed properties and functions can't rely on the general fact that it binds DNA, we need to consider details in terms of specific residues and their spatial arrangement. In particular, it would be interesting to correlate the conservation patterns of key residues with their potential to make specific DNA binding interactions. Unfortunately, no APSES domain structures in complex with bound DNA has been solved up to now, and the experimental evidence we have considered in Assignment 2 ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=10747782 Taylor ''et al.'', 2000]) is not sufficient to unambiguously define the details of how a DNA double helix might be bound. Moreover, at least two distinct modes of DNA binding are known for proteins of the winged-helix superfamily, of which the APSES domain is a member. |

| − | + | ''In this assignment you will (1) construct a molecular model of the APSES domain from the Mbp1 orthologue in your assigned species, (2) identify similar structures of distantly related domains for which protein-DNA complexes are known, (3) assemble a hypothetical complex structure and(4) discuss whether the available evidence allows you to distinguish between different modes of ligand binding, '' | |

| − | + | For the following, please remember the following terminology: | |

| − | + | ;Target | |

| − | + | :The protein that you are planning to model. | |

| − | + | ;Template | |

| − | + | :The protein whose structure you are using as a guide to build the model. | |

| − | + | ;Model | |

| − | + | :The structure that results from the modeling process. It has the '''Target sequence''' and is similar to the '''Template structure'''. | |

| − | + | | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | A brief overview article on the construction and use of homology models is linked to the resource section at the bottom of this page. That section also contains links to other sites and resources you might find useful or interesting. | |

{{Template:Preparation| | {{Template:Preparation| | ||

| − | care=Be sure you have understood all parts of the assignment and cover all questions in your answers! Sadly, we | + | care=Be sure you have understood all parts of the assignment and cover all questions in your answers! Sadly, we see too many assignments which, arduously effected, nevertheless intimate nescience of elementary tenets of molecular biology. If the sentence above did not trigger an urge to open a dictionary, you are trying to guess, rather than confirm possibly important information.| |

num=5| | num=5| | ||

ord=fifth| | ord=fifth| | ||

| − | due = | + | due = Monday, December 5. at 12:00 noon}} |

| | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Your documentation for the procedures you follow in this assignment will be worth 2 marks - 1 mark for generating the model and 1 mark for the selection/superposition and visualization of protein/DNA complexes. | ||

| + | |||

| | ||

| + | |||

<div style="padding: 5px; background: #BDC3DC; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #BDC3DC; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| − | ==(1) | + | ==(1) Preparation== |

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| + | ===(1.1) Template choice and template sequence=== | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | The [http://swissmodel.expasy.org/ SWISS-MODEL] server provides several different options for constructing homology models. The easiest is probably the '''Automated Mode''' that requires only a target sequence as input, in this mode the program will automatically choose suitable templates and create an input alignment. I disagree however that that is the best way to use such a service: the reason is that template choice and alignment both may be significantly influenced by biochemical reasoning, and an automated algorithm cannot make the necessary decisions. Should you use a structure of reduced resolution that however has a ligand bound? Should you move an indel from an active site to a loop region even though the sequence similarity score might be less? Questions like that may yield answers that are counter to the best choices an automated algorithm could make. Therefore we will use the '''Alignment Mode''' of Swiss-Model in this assignment, choose our own template and upload our own alignment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Template choice is the first step. Often more than one related structure can be found in the PDB. We have touched on principles of selecting template structures in the lecture and I have posted a short summary of [[Template_choice_principles|template choice principles]] on this Wiki. One can either search the PDB itself through its '''Advanced Search''' interface; for example one can search for sequence similarity with a BLAST search, or search for structural similarity by accessing structures according to their CATH or SCOP classification. But one can always also use the BLAST interface at the NCBI, since the sequences contained in PDB files are accessible as a database subsection on the BLAST menu. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #DDDDEE;"> | ||

| + | In assignment 2 you have already searched for structures of APSES domains in the PDB. If you need to repeat this: | ||

| + | *Use the NCBI BLAST interface to identify all PDB files that are clearly homologous to your target APSES domain. | ||

| + | *In Assignment 2, you have defined the extent of the APSES domain in yeast Mbp1. In Assignment 3, you have aligned reference APSES domains with those you found in your species. In assignment 4 you have confirmed by phylogenetic analysis and ''Recoprocal Best Match'' which of these APSES domain sequences is the closest related orthologue to yeast Mbp1. This sequence is the best candidate for having a conserved function similar to yeast Mbp1. Therefore, this sequence is the '''target''' for the homology modeling procedure. | ||

| + | *Defining a ''template''' means finding a PDB coordinate set that has sufficient sequence similarity to your '''target'' that you can huild a model based on theat '''template'''. To find suitable PDB structures, use your '''target''' sequence as input for a BLAST search, and select Protein Data Bank proteins(pdb) as the '''Database''' you search in. Hits that are homologues are all suitable '''templates''' in principle, but some are more suitable than others. Consider how the coordinate sets differ and which features would make each more or less suitable for creating a homology model; comment briefly on | ||

| + | :*sequence similarity to your target | ||

| + | :*size of expected model (= length of alignment) | ||

| + | :*presence or absence of ligands | ||

| + | :*experimental method and quality of the data set | ||

| + | Then choose the '''template''' you consider the most suitable and note why you have decided to use this template. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | It is not straightforward at all how to number sequence in such a project. The "natural" numbering starts with the start-codon of the full length protein and goes sequentially from there. However, this does not map exactly to other numbering schemes we have encountered. As you know the first residue of the APSES domain (as defined by CDD) is not Residue 1 of the Mbp1 protein. The first residue of the 1MB1 FASTA file <small>(one of the related PDB strcuctures)</small> '''is''' the first residue of Mbp1 protein, but the last five residues are an artifical His tag. Is H125 of 1MB1 thus equivalent to R125 in MBP1_SACCE? The N-terminus of the Mbp1 crystal structure is disordered. The first residue in the structure is ASN 3, therefore N is the first residue in a FASTA sequence derived from the cordinate section of the PDB file (the <code>ATOM </code> records; whereas the SEQRES records start with MET ... and so on. You need to remember: a sequence number is not absolute, but assigned in a particular context. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The homology '''model''' will be based on an alignment of '''target''' and '''template'''. Thus we have to define the target sequence. As discussed in class, PDB files have an explicit and an implied sequence and these do not necessarily have to be the same. To compare the implied and the explicit sequence for the template, you need to extract sequence information from coordinates. One way to do this is via the Web interface for [http://swift.cmbi.ru.nl/servers/html/index.html '''WhatIf'''], a crystallography and molecular modeling package that offers many useful tools for coordinate manipulation tasks. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #DDDDEE;"> | ||

| + | *Navigate to the '''Administration''' sub-menu of the [http://swift.cmbi.ru.nl/servers/html/index.html WhatIf Web server]. Follow the link to '''Make sequence file from PDB file'''. Enter the PDB-ID of your template into the form field and '''Send''' the request to the server. The server accesses the PDB file and extracts sequence information directly from the <code>ATOM </code> records of the file. The results will be returned in PIR format. Copy the results, edit them to FASTA format and save them in a text-only file. Make sure you create a valid FASTA formatted file! Use this '''implied''' sequence to check if and how it differs from the sequence ... | ||

| + | |||

| + | :*... listed in the <code>SEQRES</code> records of the coordinate file; | ||

| + | :*... given in the FASTA sequence for the template, which is provided by the PDB; | ||

| + | :*... stored in the protein database of the NCBI. | ||

| + | : and record your results. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Establish how the sequence numbers in the coordinate section of your template(*) correspond to your target sequence numbering. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :(*) <small>These residue numbers are important, since they are referenced e.g. by VMD when you visualize the structure. The easiest way to list them is via the ''Sequence Viewer'' extension of VMD.</small>. | ||

| + | :<small>Don't do this for every residue individually but define ranges. Look at the correspondence of the first and last residue of target and template sequence and take indels into account. Establishing sequence correspondence precisely is crucially important! For example, when a publication refers to a residue by its sequence number, you have to be able to relate that number to the residue numbers of the model as well as your target sequence.</small>. | ||

| | ||

| | ||

<div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| − | ===(1. | + | |

| + | ===(1.2) The input alignment=== | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | The sequence alignment between target and template is the single most important factor that determines the quality of your model. No comparative modeling process will repair an incorrect alignment; it is useful to consider a homology model rather like a three-dimensional map of a sequence alignment rather than a structure in its own right. In a homology modeling project, typically the largest amount of time should be spent on preparing the best possible alignment. Even though automated servers like the SwissModel server will align sequences and select template structures for you, it would be unwise to use these only because they are convenient. You should take advantage of the much more sophisticated alignment methods available. Analysis of wrong models can't be expected to produce right results. | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The best possible alignment is usually constructed from a multiple sequence alignment that includes at least '''the target and template sequence''' and other related sequences as well. The additional sequences are an important aid in identifying the correct placement of insertions and deletions. Your alignment should have been carefully reviewed by you and wherever required, manually adjusted to move insertions or deletions between target and template out of the secondary structure elements of the template structure. |

| − | + | In most of the Mbp1 orthologues, we do not observe indels in the APSES domain regions - (and for the ones in which we do see indels, we might suspect that these are actually gene-model errors). Evolutionary pressure on the APSES domains has selected against indels in the more than 600 million years these sequences have evolved independently in their respective species. To obtain an alignment between the '''template sequence''' and the '''target sequence''' from your species, proceed as follows. | |

| − | In | ||

| − | + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #DDDDEE;"> | |

| + | ;In Jalview... | ||

| + | * Load your Jalview project with aligned APSES domain sequences or recreate it from the Mbp1 orthologue in your species and the APSES domains from the [[Reference APSES domain sequences (reference species)|'''Reference APSES domain page''']] that I prepared for Assignment 4. Include the sequence of your '''template protein''' and re-align. | ||

| + | * Delete all sequence you no longer need, i.e. keep only the APSES domains of the '''target''' (from your species) and the '''template''' (from the PDB) and choose '''Edit → Remove empty columns'''. This is your '''input alignment'''. | ||

| + | * Choose '''File→Output to textbox→FASTA''' to obtain the aligned sequences. They should both have exactly the same length, i.e. N- or C- termini have to be padded by hyphens if the original sequences had different length. Save the sequences in a text-file. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ''' | + | ;Using a different MSA program |

| + | * Copy the FASTA formatted sequences of the Mbp1 proteins in the reference species from the [[Reference APSES domain sequences (reference species)|'''Reference APSES domain page''']]. | ||

| + | * Access e.g. the MSA tools page at the EBI. | ||

| + | * Paste the Mbp1 sequence set, your '''target''' sequence and the '''template''' sequence into the input form. | ||

| + | *Run the alignment and save the output. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ;By hand | |

| + | APSES domains are strongly conserved and have few if any indels. You could also simply align by hand. | ||

| − | + | * Copy the CLUSTAL formatted reference alignment of the Mbp1 proteins in the reference species from the [[Reference APSES domain sequences (reference species)|'''Reference APSES domain page''']]. | |

| − | + | * Open a new file in a text editor. | |

| + | * Paste the Mbp1 sequence set, your '''target''' sequence and the '''template''' sequence into the file. | ||

| + | *Align by hand, replace all spaces with hyphens and save the output. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | Whatever method you use: the result should be a multiple sequence alignment in '''multi-FASTA''' format, that was constructed from a number of supporting sequences and that contains your aligned '''target''' and '''template''' sequence. This is your '''input alignment''' for the homology modeling server. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #BDC3DC; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | |

| + | |||

| + | ==(2) Homology model== | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | | ||

| + | | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| + | === (2.1) SwissModel=== | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| − | + | Access the Swissmodel server at '''http://swissmodel.expasy.org''' . Navigate to the '''Alignment Mode''' page. | |

| − | < | + | <br><div style="padding: 5px; background: #DDDDEE;"> |

| − | : | + | *Paste your alignment for target and model into the form field. Refer to the [[Homology_modeling_fallback_data|'''Fallback Data file''']] if you are not sure about the format. Make sure to select the correct option (FASTA) for the alignment input format on the form. |

| − | + | * Click '''submit alignment ''' and on the returned page define your '''target''' and '''template''' sequence. For the '''template sequence''' define the PDB ID of the coordinate file it came from. Enter the correct Chain-ID <small>(usually "A", note: upper-case)</small>. | |

| + | :<small>If you run into problems, compare your input to the fallback data. It has worked for me, it will work for you. In particular we have seen problems that arise from "special" characters in the FASTA header like the pipe "<code>|</code>" character that the NCBI uses to separate IDs - keep the header short and remove all non-alphanumeric characters to be safe.</small> | ||

| − | + | *Click '''submit alignment''' and review the alignment on the returned page. Make sure it has been interpreted correctly by the server. '''The conserved residues have to be lined up and matching'''. Then click '''submit alignment''' again, to start the modeling process. | |

| − | + | * The resulting page returns information about the resulting model. Save the '''model coordinates''' on your computer. Read the information on what is being returned by the server (click on the red questionmark icon). Paste the Anolea profile into your assignment. | |

| − | </ | + | :<small>Do not paste a screenshot of the result, but copy and paste the image from the Web-page! You do not need to submit the actual coordinate files with your assignment.</small> |

| + | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #BDC3DC; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| − | + | ==(3) Model analysis== | |

| + | </div> | ||

| + | | ||

| + | | ||

| − | ==== | + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> |

| + | === (3.1) The PDB file === | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| − | + | Open your '''model''' coordinates in a text-editor (make sure you view the PDB file in a fixed-width font) and consider the following questions: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <br><div style="padding: 5px; background: #DDDDEE;"> | |

| + | *What is the residue number of the first residue in the '''model'''? What should it be, based on the alignment? If the putative DNA binding region was reported to be residues 50-74 in the Mbp1 protein, which residues of your '''model''' correspond to that region? | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <!-- discuss flagging of loops - setting of B-factor to 99.0 phps. ANOLEA vs. Gromos ... packing vs. energy? --> | ||

| − | |||

| + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| + | ===(3.2) First visualization=== | ||

| + | </div> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In assignment 2 you have already studied a Mbp1 structure and compared it with your organism's Mbp1 APSES domain, Since a homology model inherits its structural details from the '''template''', the model should look very similar to the original structure but contain the sequence of the '''target'''. | |

| + | |||

| + | <br><div style="padding: 5px; background: #DDDDEE;"> | ||

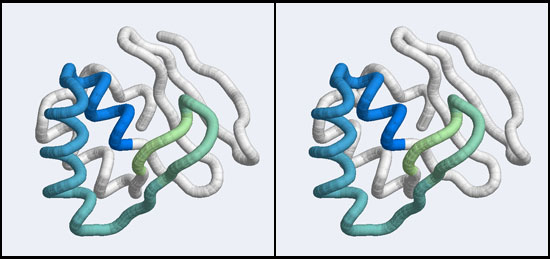

| + | *Save your '''model''' coordinates to your computer and visualize the structure in VMD. Make an informative (parallel, not cross-eyed!) stereo view that shows the general orientation of the helix-turn-helix motif and the "wing", and paste it into your assignment. | ||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #BDC3DC; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==(4) The DNA ligand== | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | | ||

| + | | ||

<div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| − | ===(1 | + | ===(4.1) Finding a similar protein-DNA complex=== |

</div> | </div> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| + | One of the really interesting questions we can discuss with reference to our model is how sequence variation might result in changed DNA recognition sites, and then lead to changed cognate DNA binding sequences. In order to address this, we would need to generate a plausible structural model for how DNA is bound to APSES domains. | ||

| − | + | Since there is currently no software available that would accurately model such a complex from first principles, we will base a model of a bound complex on homology modeling as well. This means we need to find a similar structure for which the position of bound DNA is known, then superimpose that structure with our model. This places the DNA molecule into the spatial context of the model we are studying. However, you may remember from the third assignment that the APSES domains in fungi seem to be a relatively small family. And there is no structure available of an APSES domain-DNA complex. How can we find a coordinate set of a structurally similar protein-DNA complex? | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Remember that homologous sequences can have diverged to the point where their sequence similarity is no longer recognizable, however their structure may be quite well conserved. Thus if we could find similar structures in the PDB, these might provide us with some plausible hypotheses for how DNA is bound by APSES domains. We thus need a tool similar to BLAST, but not for the purpose of sequence alignment, but for structure alignment. A kind of BLAST for structures. Just like with sequence searches, we might not want to search with the entire protein, if we are interested in is a subdomain that binds to DNA. Attempting to match all structural elements in addition to the ones we are actually interested in is likely to make the search less specific - we would find false positives that are similar to some irrelevant part of our structure. However, defining too small of a subdomain would also lead to a loss of specificity: in the extreme it is easy to imagine that the search for e.g. a single helix would retrieve very many hits that would be quite meaningless. | |

| − | + | At the '''NCBI''', [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/VAST/vast.shtml VAST] is provided as a search tool for structural similarity search. | |

| − | + | At the '''EBI''' there are a number of very well designed structure analysis tools linked off the [http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/structural.html '''Structural Analysis''' page]. As part of its MSD Services, [http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/ssm/ '''PDBeFold'''] provides a convenient interface for structure searches. | |

| − | + | However we have also read previously that the APSES domains are members of a much larger superfamily, the "winged helix" DNA binding domains , of which hundreds of structures have been solved. | |

| − | + | <br> | |

| + | [[Image:A5_Mbp1_subdomain.jpg|frame|none|Stereo-view of a subdomain within the 1MB1 structure that includes residues 36 to 76. The color gradient ramps from blue (36) to green (76) and the "wing" is clearly seen as the green pair of beta-strands, extending to the right of the helix-turn-helix motif.]] | ||

| − | < | + | <br> |

| − | + | APSES domains represent one branch of the tree of helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA binding modules. (A review on HTH proteins is linked from the resources section at the bottom of this page). Winged Helix domains typically bind their cognate DNA with a "recognition helix" which precedes the beta hairpin and binds into the major groove; additional stabilizing interactions are provided by the edge of a beta-strand binding into the minor groove. This is good news: once we have determined that the APSES domain is actually an example of a larger group of transcription factors, we can compare our model to a structure of a protein-DNA complex. Superfamilies of such structural domains are compiled in the CATH database. Unfortunately CATH itself does not provide information about whether the structures have been determined as complexes. '''But''' we can search the PDB with CATH codes and restrict the results to complexes. Essentially, this should give us a list of all winged helix domains for which the structure of complexes with DNA have been determined. This works as follows: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | * For reference, access [http://cathwww.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/cgi-bin/cath/GotoCath.pl?cath=1.10.10.10 CATH domain 1.10.10.10]; this is the domain you will use to find protein-DNA complexes. | |

| + | * Navigate to the [http://www.pdb.org/ PDB home page] and follow the link to [http://www.pdb.org/pdb/search/advSearch.do Advanced Search] | ||

| + | * In the options menu for "Choose a Query Type" select Structure Features → CATH Classification Browser. A window will open that allows you to navigate down through the CATH tree. You can view the Class/Architecture/Topology names on the CATH page linked above. Click on '''the triangle icons''' (not the text) for "Mainly Alpha"→"Orthogonal Bundle"→"ARC repressor mutant, subunit A" then click on the link to "winged helix repressor DNA binding domain". Or, just enter "winged helix" into the search field. This subquery should match more than 500 coordinate entries. | ||

| + | * Click on the (+) button behind "Add search criteria" to add an additional query. Select the option "Structure Features"→"Macromolecule type". In the option menus that pop up, select "Contains Protein → Yes", "Contains DNA → Yes""Contains RNA → Ignore" "Contains DNA/RNA hybrid → Ignore". This selects files that contain Protein-DNA complexes. | ||

| + | * Check the box below this subquery to "Remove Similar Sequences at 90% identity" and click on "Submit Query". This query should retrieve more than 90 complexes. | ||

| + | * Scroll down to the beginning of the list of PDB codes and locate the "Generate reports" menu. Under the heading '''Custom reports''' select '''Image collage'''. This is a fast way to obtain an overview of the structures that have been returned. First of all you may notice that in fact not all of the structures are really different, despite selecting only to retrieve dissimilar sequences. This appears to be a deficiency of the algorithm. But you can also easily recognize how in most of the the structures the '''recognition helix inserts into the major groove of B-DNA''' (eg. 1BC8, 1CF7). There is one exception: the structure 1DP7 shows how the human RFX1 protein binds DNA in a non-canonical way, through the beta-strands of the "wing". This is interesting since it suggests there is more than one way for winged helix domains to bind to DNA. We can therefore use structural superposition of '''your homology model''' and '''two of the winged-helix proteins''' to decide whether the canonical or the non-canonical mode of DNA binding seems to be more plausible for Mbp1 orthologues. | ||

| − | = | + | <br><div style="padding: 5px; background: #DDDDEE;"> |

| + | * Follow the procedure outlined above, from a CATH entry page up to viewing a Collage (or alternatively a tabular view) of the retrieved coordinate files. You can be maximally concise in your documentation for the procedure I have defined above, but I expect you to have spent enough time on this process to understand the key elements of the PDB's advanced search interface. | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | |

| − | + | ===(4.2) Preparation and superposition of a canonical complex=== | |

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

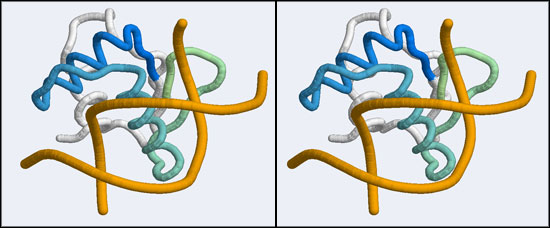

| − | + | The structure we shall use as a reference for the '''canonical binding mode''' is the Elk-1 transcription factor. | |

| − | + | [[Image:A5_canonical_wHTH.jpg|frame|none|Stereo-view of the canonical DNA binding mode of the Winged Helix domain family. Shown here is the Elk-1 transcription factor - an ETS DNA binding domain - in complex with a high-affinity binding site (1DUX). Note how the "recognition helix" inserts into the major groove of the DNA molecule. The color gradient ramps from blue (34) to green (84). Note how the first helix of the "helix-turn-helix" architecture serves only to position the recognition helix and makes few interactions by itself.]] | |

| − | B | + | The 1DUX coordinate-file contains two protein domains and two B-DNA dimers in one asymmetric unit. For simplicity, you should delete the second copy of the complex from the PDB file. (Remember that PDB files are simply text files that can be edited.) |

| − | + | * Access the PDB and navigate to the 1DUX structure explorer page. Download the coordinates to your computer. | |

| + | * Open the coordinate file in a text-editor and delete the coordinates for chains <code>D</code>,<code>E</code> and <code>F</code>; you may also delete all <code>HETATM</code> records and the <code>MASTER</code> record. Save the file with a different name, e.g. 1DUX_monomer.pdb . | ||

| + | * Open VMD and load your homology model. Turn off the axes, display the model as a Tube representation in stereo, and color it by Index. Then load your edited 1DUX file, display this coordinate set in a tube representation as well, and color it by ColorID in some color you like. It is important that you can distinguish easily which structure is which | ||

| + | * You could use the Extensions→Analysis→RMSD calculator interface to superimpose the two strutcures '''IF''' you would know which residues correspond to each other. Sometimes it is useful to do exactly that: define exact correspondences between residue pairs and superimpose according to these selected pairs. For our purpose it is much simpler to use the Multiseq tool (and the structures are simple and small enough that the STAMP algorithm for structural alignment can define corresponding residue pairs automatically). Open the '''multiseq''' extension window, select the check-boxes next to both protein structures, and open the '''Tools→Stamp Structural Alignment''' interface. | ||

| + | * In the "'Stamp Alignment Options'" window, check the radio-button for ''Align the following ...'' '''Marked Structures''' and click on '''OK'''. | ||

| + | * In the '''Graphical Representations''' window, double-click on all "NewCartoon" representations for both molecules, to undisplay them. | ||

| + | * You should now see a superimposed tube model of your homology model and the 1DUX protein-DNA complex. You can explore it, display side-chains etc. and study some of the details of how a transcription factor recognizes and binds to its cognate DNA sequence. However, remember that your '''model''''s side-chain orientations have not been determined experimentally but inferred from the '''template''', and that the template's structure was determined in the absence of bound DNA ligand. | ||

| + | <br><div style="padding: 5px; background: #DDDDEE;"> | ||

| + | * Orient and scale your superimposed structures so that their structural similarity is apparent, and the recognition helix can be clearly seen inserting into the DNA major groove. Paste a copy of your image into your assignment. Remark briefly on which parts of the structure appear to superimpose best. Note whether this orientation of a B-DNA double-helix is a plausible model for DNA binding of your Mbp1 orthologue. | ||

| − | | + | </div> |

| + | <br> | ||

| | ||

| Line 185: | Line 273: | ||

<div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| − | ===( | + | ===(4.2) Preparation and superposition of a non-canonical complex=== |

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

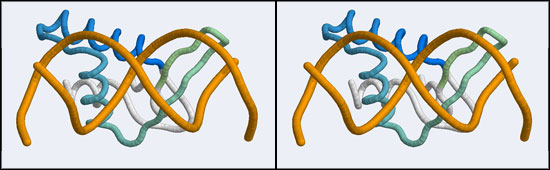

| − | + | The structure displaying a non-canonical complex between a winged-helix domain and its cognate DNA binding site is the human Regulatory Factor X. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | [[Image:A5_non-canonical_wHTH.jpg|frame|none|Stereo-view of a non-canonical wHTH-DNA complex, discovered in with the stucture of human Regulatory Factor X (hRFX) binding its cognate X-box DNA sequence (1DP7). Note how the helix that coresponds to the recognition helix in the canonical domain lies across the minor groove whereas the beta-"wing" inserts into the major groove. The color gradient ramps from blue (18) to green (68).]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Before we can work with this however, we have to fix an annoying problem caused by the way the PDB stores replicates in biological assemblies. The PDB generates additional chains as copies of the original and delineates them with <code>MODEL</code> and <code>ENDMDL</code> records, just like in a multi-structure NMR file. The chain IDs and the atom numbers are the same as the original. The PDB file thus contains the '''same molecule in two different orientations''', not '''two independent molecules'''. This is an important difference regarding how such molecules are displayed by VMD. If you were to use the biological unit file of the PDB, VMD does not recognize that there is a second molecule present and displays only one. We have to edit the file to merge the two molecules by removing the MODEL and ENDMDL records - and while we're editing the file we'll also remove unneeded heteroatoms and the second copy of the protein chain (which we don't need, we need only the second B-DNA strand). But then we end up with residues that have '''exactly the same residue number''' in the same file. That won't work for visualization, since the program expects residue numbers to be unique, therefore we have to renumber the residues. Here's how: | ||

| − | < | + | * On the structure explorer page for 1DP7, select the option '''Download Files''' → '''Biological Assembly'''. |

| + | * Dowload, save and uncompress the file. | ||

| + | * Open the file in a text editor. | ||

| + | * Delete both <code>MODEL</code> and both <code>ENDMDL</code> records. | ||

| + | * Also delete all <code>HETATM</code> records for <code>HOH</code>, <code>PEG</code> and <code>EDO</code>, as well as the entire second protein chain and the <code>MASTER</code> record. The resulting file should only contain the DNA chain and its copy and one protein chain. Save the file with a new name. | ||

| + | * Access the [http://swift.cmbi.ru.nl/servers/html/index.html '''Whatif Web interface'''] and click on '''Administration''' and '''Renumber a PDB File from 1'''. Upload your edited file, access the results and save the file. | ||

| + | * Open the renumbered file with VMD. You should see '''one protein chain''' and a '''B-DNA double helix'''. Switch to stereo viewing and spend some time to see how '''amazingly beautiful''' the complementarity between the protein and the DNA helix is (you might want to display ''chain P'' and ''chain D'' in separate representations and color the DNA chain by ''Position'' → ''Radial'' for clarity) ... in particular, appreciate how Arginine 76 interacts with the base of Guanine 92! | ||

| + | * Then clear all molecules | ||

| + | * In VMD, open '''Extensions→Analysis→MultiSeq'''. When you run MultiSeq for the first time, you will be asked for a directory in which to store metadata. You can use the default, or a directory of your choice; you may subsequently skip all steps that ask you to install "required" databases locally since we will not need them for this task. | ||

| + | * A window will appear - the MultiSeq window - it contains the sequence of the APSES domain you are visualizing. MultiSeq will also generate an additional cartoon representation of the structure. Choose '''File→Import Data''', browse to your directory and load: | ||

| + | ** Your model; | ||

| + | ** The 1DUX complex; | ||

| + | ** The 1DP7 complex. | ||

| + | * Mark all three protein chains by selecting the checkbox next to their name and run the STAMP structural alignment. | ||

| + | * In the graphical representations window, double-click on the cartoon representations that multiseq has generated to undisplay them, also undisplay the Tube representation of 1DUX. Then create a Tube representation for 1DP7, and select a Color by ColorID (a different color that you like). The resulting scene should look similar to the one you have created above, only with 1DP7 in place of 1DUX and colored differently. | ||

| − | * | + | <br><div style="padding: 5px; background: #DDDDEE;"> |

| + | * Orient and scale your superimposed structures so that their structural similarity is apparent, the orientation is similar to the scene generated above and the 1DP7 "wing" can be clearly seen inserting into the DNA major groove. Paste a copy of your image into your assignment. Remark briefly on which parts of the structure appear to superimpose best. Note whether this orientation of a B-DNA double-helix is a plausible model for DNA binding of your Mbp1 orthologue. | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

<div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| − | ===( | + | ===(4.3) Coloring by conservation=== |

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | With the superimposed coordinates, you can begin to get a sense whether either or both binding modes could be appropriate for a protein-DNA complex in your Mbp1 orthologue. But these are geometrical criteria only, and the protein in your species may be flexible enough to adopt a different conformation in a complex, and different again from your model. A more powerful way to analyze such hypothetical complexes is to look at conservation patterns. With VMD, you can import a sequence alignment into the MultiSeq extension and color residies by conservation. The protocol below assumes | |

| + | |||

| + | *You have prealigned the reference Mbp1 proteins with your species' Mbp1 orthologue; | ||

| + | *You have saved the alignment in a CLUSTAL format. | ||

| + | |||

| + | You can use Jalview or any other MSA server to do so. You can even do this by hand - there should be few if any indels and the correct alignment is easy to see. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ;Load the Mbp1 APSES alignment into MultiSeq. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :(A) In the MultiSeq Window, navigate to '''File → Import Data...'''; Choose "From Files" and Browse to the location of the alignment you have saved. The File navigation window gives you options which files to enable: choose to Enable <code>ALN</code> files (these are CLUSTAL formatted multiple sequence alignments). | ||

| + | :(B) Open the alignment file, click on '''Ok''' to import the data, it will take a short while to load. If the data can't be loaded, the file may have the wrong extension: .aln is required. | ||

| + | :(C) find the Mbp1_SACCE sequence in the list, click on it and move it to the top of the Sequences list with your mouse (the list is not static, you can re-order the sequences in any way you like). | ||

| + | |||

| + | You will see that the 1MB1 sequence and the APSES domain sequence do not match: at the N-terminus the sequence that corresponds to the PDB structure has extra residues, and in the middle the APSES sequences may have gaps inserted. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Bring the 1MB1 sequence in register with the APSES alignment. | ||

| + | :(A)MultiSeq supports typical text-editor selection mechanisms. Clicking on a residue selects it, clicking on a row selects the whole sequence. Dragging with the mouse selects several residues, shift-clicking selects ranges, and option-clicking toggles the selection on or off for individual residues. Using the mouse and/or the shift key as required, select the '''entire first column''' of the sequences you have imported. | ||

| + | :(B) Select '''Edit → Enable Editing... → Gaps only''' to allow changing indels. | ||

| + | :(C) Pressing the spacebar once should insert a gap character before the '''selected column''' in all sequences. Insert as many gaps as you need to align the beginning of sequences with the corresponding residues of 1MB1: <code>S I M ...</code> | ||

| + | :(D) Now insert as many gaps as you need into the structure sequence, to align it completely with the Mbp1_SACCE APSES domain sequence. (Simply select residues in the sequence and use the space bar to insert gaps. (Note: I have noticed a bug that sometimes prevents slider or keyboard input to the MultiSeq window; it fails to regain focus after operations in a different window. I don't know whether this is a Mac related problem or a more general bug in MultiSeq. When this happens I quit VMD and restore the session from a saved state. It is a bit annoying but not mission-critical.) | ||

| + | :(E) When you are done, it may be prudent to save the state of your alignment. Use '''File → Save Session...''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Color by similarity | ||

| + | :(A) Use the '''View → Coloring → Sequence similarity → BLOSUM30''' option to color the residues in the alignment and structure. This clearly shows you where conserved and variable residues are located and allows to analyze their structural context. | ||

| + | :(B) You can adjust the color scale in the usual way by navigating to '''VMD main → Graphics → Colors...''', choosing the Color Scale tab and adjusting the scale midpoint. | ||

| + | :(C) Navigate to the '''Representations''' window and apply the color scheme to your tube-and-sidechain representation: double-click on the NewCartoon representation to hide it and use '''User''' coloring of your ''Tube'' and ''Licorice'' representations to apply the sequence similarity color gradient that MultiSeq has calculated. | ||

| − | <br><div style="padding: 5px; background: # | + | <br><div style="padding: 5px; background: #DDDDEE;"> |

| − | * | + | * Once you have colored the residues of your model by conservation, create another informative stereo-image and paste it into your assignment. |

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #E9EBF3; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | |

| − | + | ===(4.4) Interpretation=== | |

| + | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #FFCC99;"> | |

| − | * | + | ;Analysis (2 marks) |

| + | * Considering the conservation patterns for Mbp1 orthologues, and assuming that all these orthologues bind DNA in a similar way, which model appears to be more plausible for protein-DNA interactions in APSES domains? Is it the canonical, or the non-canonical binding mode? Discuss briefly what you would expect to find and how this relates to your observations. Distinguish clearly between experimental evidence, computational inference and empirical hypothesis. You are welcome to upload detail views (stereo !) of particular sidechains, or surfaces etc. if this helps your arguments. Sometimes a picture is worth many words. But this is not a requirement, we are more interested in evidence-based reasoning than in the form of the presentation. | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<div style="padding: 5px; background: #BDC3DC; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | <div style="padding: 5px; background: #BDC3DC; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA;"> | ||

| − | ==( | + | ==(5) Summary of Resources== |

</div> | </div> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | ;Links | + | ;Links and background reading |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :* [http://biochemistry.utoronto.ca/undergraduates/courses/BCH441H/restricted/Peitsch_2002_UseOfModels.pdf '''Review (PDF, restricted)''' Manuel Peitsch on Homology Modeling] | |

| − | :* [[ | + | :* [http://biochemistry.utoronto.ca/undergraduates/courses/BCH441H/restricted/Aravind_2005_HTHdomains.pdf '''Review (PDF, restricted)''' Aravind ''et al.'' Helix-turn-helix domains] |

| + | :* [http://biochemistry.utoronto.ca/undergraduates/courses/BCH441H/restricted/2000_Gajiwala_WingedHelixDomains.pdf '''Review (PDF, restricted)''' Gajiwala & Burley, winged-Helix domains] | ||

| + | :* [http://www.wwpdb.org/documentation/format23/v2.3.html '''PDB file format'''] (see the Coordinate Section if you are unsure about chain identifiers) | ||

| + | :* [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structural_alignment Wikipedia on '''Structural Superposition'''] <small>(although the article is called "Structural Alignment")</small> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ; | + | ;Data |

| − | |||

| − | + | :* [[Homology_modeling_fallback_data|'''Fallback Data page''']] <small> - Refer to this page in case your own efforts fail, or you have insurmountable problems with your input files.</small> | |

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Reference sequences and alignments | ||

| + | |||

| + | :* [[Reference APSES domain sequences (reference species)|'''Reference APSES domains page''']] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{Template:Assignment_Footer}} | |

Latest revision as of 17:51, 1 December 2014

Note! This assignment is currently active. All significant changes will be announced on the mailing list.

Contents

Assignment 5 (last: 2011) - Homology modeling

- How could the search for ultimate truth have revealed so hideous and visceral-looking an object?

-

- Max Perutz (on his first glimpse of the Hemoglobin structure)

Where is the hidden beauty in structure, and where, the "ultimate truth"? In the previous assignments we have studied sequence conservation in APSES family domains and we have discovered homologues in all fungal species. This is an ancient protein family that had already duplicated to several paralogues at the time the cenancestor of all fungi lived, more than 600,000,000 years ago, in the Vendian period of the Proterozoic era of Precambrian times.

In order to understand how specific residues in the sequence contribute to the putative function of the protein, and why and how they are conserved throughout evolution, we would need to study an explicit molecular model of an APSES domain protein, bound to its cognate DNA sequence. Explanations of a protein's observed properties and functions can't rely on the general fact that it binds DNA, we need to consider details in terms of specific residues and their spatial arrangement. In particular, it would be interesting to correlate the conservation patterns of key residues with their potential to make specific DNA binding interactions. Unfortunately, no APSES domain structures in complex with bound DNA has been solved up to now, and the experimental evidence we have considered in Assignment 2 (Taylor et al., 2000) is not sufficient to unambiguously define the details of how a DNA double helix might be bound. Moreover, at least two distinct modes of DNA binding are known for proteins of the winged-helix superfamily, of which the APSES domain is a member.

In this assignment you will (1) construct a molecular model of the APSES domain from the Mbp1 orthologue in your assigned species, (2) identify similar structures of distantly related domains for which protein-DNA complexes are known, (3) assemble a hypothetical complex structure and(4) discuss whether the available evidence allows you to distinguish between different modes of ligand binding,

For the following, please remember the following terminology:

- Target

- The protein that you are planning to model.

- Template

- The protein whose structure you are using as a guide to build the model.

- Model

- The structure that results from the modeling process. It has the Target sequence and is similar to the Template structure.

A brief overview article on the construction and use of homology models is linked to the resource section at the bottom of this page. That section also contains links to other sites and resources you might find useful or interesting.

Preparation, submission and due date

- Read carefully.

- Be sure you have understood all parts of the assignment and cover all questions in your answers! Sadly, we see too many assignments which, arduously effected, nevertheless intimate nescience of elementary tenets of molecular biology. If the sentence above did not trigger an urge to open a dictionary, you are trying to guess, rather than confirm possibly important information.

Review the guidelines for preparation and submission of BCH441 assignments.

The due date for the assignment is Monday, December 5. at 12:00 noon.

- Your documentation for the procedures you follow in this assignment will be worth 2 marks - 1 mark for generating the model and 1 mark for the selection/superposition and visualization of protein/DNA complexes.

(1) Preparation

(1.1) Template choice and template sequence

The SWISS-MODEL server provides several different options for constructing homology models. The easiest is probably the Automated Mode that requires only a target sequence as input, in this mode the program will automatically choose suitable templates and create an input alignment. I disagree however that that is the best way to use such a service: the reason is that template choice and alignment both may be significantly influenced by biochemical reasoning, and an automated algorithm cannot make the necessary decisions. Should you use a structure of reduced resolution that however has a ligand bound? Should you move an indel from an active site to a loop region even though the sequence similarity score might be less? Questions like that may yield answers that are counter to the best choices an automated algorithm could make. Therefore we will use the Alignment Mode of Swiss-Model in this assignment, choose our own template and upload our own alignment.

Template choice is the first step. Often more than one related structure can be found in the PDB. We have touched on principles of selecting template structures in the lecture and I have posted a short summary of template choice principles on this Wiki. One can either search the PDB itself through its Advanced Search interface; for example one can search for sequence similarity with a BLAST search, or search for structural similarity by accessing structures according to their CATH or SCOP classification. But one can always also use the BLAST interface at the NCBI, since the sequences contained in PDB files are accessible as a database subsection on the BLAST menu.

In assignment 2 you have already searched for structures of APSES domains in the PDB. If you need to repeat this:

- Use the NCBI BLAST interface to identify all PDB files that are clearly homologous to your target APSES domain.

- In Assignment 2, you have defined the extent of the APSES domain in yeast Mbp1. In Assignment 3, you have aligned reference APSES domains with those you found in your species. In assignment 4 you have confirmed by phylogenetic analysis and Recoprocal Best Match which of these APSES domain sequences is the closest related orthologue to yeast Mbp1. This sequence is the best candidate for having a conserved function similar to yeast Mbp1. Therefore, this sequence is the target for the homology modeling procedure.

- Defining a template means finding a PDB coordinate set that has sufficient sequence similarity to your target that you can huild a model based on theat template. To find suitable PDB structures, use your target sequence as input for a BLAST search, and select Protein Data Bank proteins(pdb) as the Database you search in. Hits that are homologues are all suitable templates in principle, but some are more suitable than others. Consider how the coordinate sets differ and which features would make each more or less suitable for creating a homology model; comment briefly on

- sequence similarity to your target

- size of expected model (= length of alignment)

- presence or absence of ligands

- experimental method and quality of the data set

Then choose the template you consider the most suitable and note why you have decided to use this template.

It is not straightforward at all how to number sequence in such a project. The "natural" numbering starts with the start-codon of the full length protein and goes sequentially from there. However, this does not map exactly to other numbering schemes we have encountered. As you know the first residue of the APSES domain (as defined by CDD) is not Residue 1 of the Mbp1 protein. The first residue of the 1MB1 FASTA file (one of the related PDB strcuctures) is the first residue of Mbp1 protein, but the last five residues are an artifical His tag. Is H125 of 1MB1 thus equivalent to R125 in MBP1_SACCE? The N-terminus of the Mbp1 crystal structure is disordered. The first residue in the structure is ASN 3, therefore N is the first residue in a FASTA sequence derived from the cordinate section of the PDB file (the ATOM records; whereas the SEQRES records start with MET ... and so on. You need to remember: a sequence number is not absolute, but assigned in a particular context.

The homology model will be based on an alignment of target and template. Thus we have to define the target sequence. As discussed in class, PDB files have an explicit and an implied sequence and these do not necessarily have to be the same. To compare the implied and the explicit sequence for the template, you need to extract sequence information from coordinates. One way to do this is via the Web interface for WhatIf, a crystallography and molecular modeling package that offers many useful tools for coordinate manipulation tasks.

- Navigate to the Administration sub-menu of the WhatIf Web server. Follow the link to Make sequence file from PDB file. Enter the PDB-ID of your template into the form field and Send the request to the server. The server accesses the PDB file and extracts sequence information directly from the

ATOMrecords of the file. The results will be returned in PIR format. Copy the results, edit them to FASTA format and save them in a text-only file. Make sure you create a valid FASTA formatted file! Use this implied sequence to check if and how it differs from the sequence ...

- ... listed in the

SEQRESrecords of the coordinate file; - ... given in the FASTA sequence for the template, which is provided by the PDB;

- ... stored in the protein database of the NCBI.

- ... listed in the

- and record your results.

- Establish how the sequence numbers in the coordinate section of your template(*) correspond to your target sequence numbering.

- (*) These residue numbers are important, since they are referenced e.g. by VMD when you visualize the structure. The easiest way to list them is via the Sequence Viewer extension of VMD..

- Don't do this for every residue individually but define ranges. Look at the correspondence of the first and last residue of target and template sequence and take indels into account. Establishing sequence correspondence precisely is crucially important! For example, when a publication refers to a residue by its sequence number, you have to be able to relate that number to the residue numbers of the model as well as your target sequence..

(1.2) The input alignment

The sequence alignment between target and template is the single most important factor that determines the quality of your model. No comparative modeling process will repair an incorrect alignment; it is useful to consider a homology model rather like a three-dimensional map of a sequence alignment rather than a structure in its own right. In a homology modeling project, typically the largest amount of time should be spent on preparing the best possible alignment. Even though automated servers like the SwissModel server will align sequences and select template structures for you, it would be unwise to use these only because they are convenient. You should take advantage of the much more sophisticated alignment methods available. Analysis of wrong models can't be expected to produce right results.

The best possible alignment is usually constructed from a multiple sequence alignment that includes at least the target and template sequence and other related sequences as well. The additional sequences are an important aid in identifying the correct placement of insertions and deletions. Your alignment should have been carefully reviewed by you and wherever required, manually adjusted to move insertions or deletions between target and template out of the secondary structure elements of the template structure.

In most of the Mbp1 orthologues, we do not observe indels in the APSES domain regions - (and for the ones in which we do see indels, we might suspect that these are actually gene-model errors). Evolutionary pressure on the APSES domains has selected against indels in the more than 600 million years these sequences have evolved independently in their respective species. To obtain an alignment between the template sequence and the target sequence from your species, proceed as follows.

- In Jalview...

- Load your Jalview project with aligned APSES domain sequences or recreate it from the Mbp1 orthologue in your species and the APSES domains from the Reference APSES domain page that I prepared for Assignment 4. Include the sequence of your template protein and re-align.

- Delete all sequence you no longer need, i.e. keep only the APSES domains of the target (from your species) and the template (from the PDB) and choose Edit → Remove empty columns. This is your input alignment.

- Choose File→Output to textbox→FASTA to obtain the aligned sequences. They should both have exactly the same length, i.e. N- or C- termini have to be padded by hyphens if the original sequences had different length. Save the sequences in a text-file.

- Using a different MSA program

- Copy the FASTA formatted sequences of the Mbp1 proteins in the reference species from the Reference APSES domain page.

- Access e.g. the MSA tools page at the EBI.

- Paste the Mbp1 sequence set, your target sequence and the template sequence into the input form.

- Run the alignment and save the output.

- By hand

APSES domains are strongly conserved and have few if any indels. You could also simply align by hand.

- Copy the CLUSTAL formatted reference alignment of the Mbp1 proteins in the reference species from the Reference APSES domain page.

- Open a new file in a text editor.

- Paste the Mbp1 sequence set, your target sequence and the template sequence into the file.

- Align by hand, replace all spaces with hyphens and save the output.

Whatever method you use: the result should be a multiple sequence alignment in multi-FASTA format, that was constructed from a number of supporting sequences and that contains your aligned target and template sequence. This is your input alignment for the homology modeling server.

(2) Homology model

(2.1) SwissModel

Access the Swissmodel server at http://swissmodel.expasy.org . Navigate to the Alignment Mode page.

- Paste your alignment for target and model into the form field. Refer to the Fallback Data file if you are not sure about the format. Make sure to select the correct option (FASTA) for the alignment input format on the form.

- Click submit alignment and on the returned page define your target and template sequence. For the template sequence define the PDB ID of the coordinate file it came from. Enter the correct Chain-ID (usually "A", note: upper-case).

- If you run into problems, compare your input to the fallback data. It has worked for me, it will work for you. In particular we have seen problems that arise from "special" characters in the FASTA header like the pipe "

|" character that the NCBI uses to separate IDs - keep the header short and remove all non-alphanumeric characters to be safe.

- Click submit alignment and review the alignment on the returned page. Make sure it has been interpreted correctly by the server. The conserved residues have to be lined up and matching. Then click submit alignment again, to start the modeling process.

- The resulting page returns information about the resulting model. Save the model coordinates on your computer. Read the information on what is being returned by the server (click on the red questionmark icon). Paste the Anolea profile into your assignment.

- Do not paste a screenshot of the result, but copy and paste the image from the Web-page! You do not need to submit the actual coordinate files with your assignment.

(3) Model analysis

(3.1) The PDB file

Open your model coordinates in a text-editor (make sure you view the PDB file in a fixed-width font) and consider the following questions:

- What is the residue number of the first residue in the model? What should it be, based on the alignment? If the putative DNA binding region was reported to be residues 50-74 in the Mbp1 protein, which residues of your model correspond to that region?

(3.2) First visualization

In assignment 2 you have already studied a Mbp1 structure and compared it with your organism's Mbp1 APSES domain, Since a homology model inherits its structural details from the template, the model should look very similar to the original structure but contain the sequence of the target.

- Save your model coordinates to your computer and visualize the structure in VMD. Make an informative (parallel, not cross-eyed!) stereo view that shows the general orientation of the helix-turn-helix motif and the "wing", and paste it into your assignment.

(4) The DNA ligand

(4.1) Finding a similar protein-DNA complex

One of the really interesting questions we can discuss with reference to our model is how sequence variation might result in changed DNA recognition sites, and then lead to changed cognate DNA binding sequences. In order to address this, we would need to generate a plausible structural model for how DNA is bound to APSES domains.

Since there is currently no software available that would accurately model such a complex from first principles, we will base a model of a bound complex on homology modeling as well. This means we need to find a similar structure for which the position of bound DNA is known, then superimpose that structure with our model. This places the DNA molecule into the spatial context of the model we are studying. However, you may remember from the third assignment that the APSES domains in fungi seem to be a relatively small family. And there is no structure available of an APSES domain-DNA complex. How can we find a coordinate set of a structurally similar protein-DNA complex?

Remember that homologous sequences can have diverged to the point where their sequence similarity is no longer recognizable, however their structure may be quite well conserved. Thus if we could find similar structures in the PDB, these might provide us with some plausible hypotheses for how DNA is bound by APSES domains. We thus need a tool similar to BLAST, but not for the purpose of sequence alignment, but for structure alignment. A kind of BLAST for structures. Just like with sequence searches, we might not want to search with the entire protein, if we are interested in is a subdomain that binds to DNA. Attempting to match all structural elements in addition to the ones we are actually interested in is likely to make the search less specific - we would find false positives that are similar to some irrelevant part of our structure. However, defining too small of a subdomain would also lead to a loss of specificity: in the extreme it is easy to imagine that the search for e.g. a single helix would retrieve very many hits that would be quite meaningless.

At the NCBI, VAST is provided as a search tool for structural similarity search.

At the EBI there are a number of very well designed structure analysis tools linked off the Structural Analysis page. As part of its MSD Services, PDBeFold provides a convenient interface for structure searches.

However we have also read previously that the APSES domains are members of a much larger superfamily, the "winged helix" DNA binding domains , of which hundreds of structures have been solved.

APSES domains represent one branch of the tree of helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA binding modules. (A review on HTH proteins is linked from the resources section at the bottom of this page). Winged Helix domains typically bind their cognate DNA with a "recognition helix" which precedes the beta hairpin and binds into the major groove; additional stabilizing interactions are provided by the edge of a beta-strand binding into the minor groove. This is good news: once we have determined that the APSES domain is actually an example of a larger group of transcription factors, we can compare our model to a structure of a protein-DNA complex. Superfamilies of such structural domains are compiled in the CATH database. Unfortunately CATH itself does not provide information about whether the structures have been determined as complexes. But we can search the PDB with CATH codes and restrict the results to complexes. Essentially, this should give us a list of all winged helix domains for which the structure of complexes with DNA have been determined. This works as follows:

- For reference, access CATH domain 1.10.10.10; this is the domain you will use to find protein-DNA complexes.

- Navigate to the PDB home page and follow the link to Advanced Search

- In the options menu for "Choose a Query Type" select Structure Features → CATH Classification Browser. A window will open that allows you to navigate down through the CATH tree. You can view the Class/Architecture/Topology names on the CATH page linked above. Click on the triangle icons (not the text) for "Mainly Alpha"→"Orthogonal Bundle"→"ARC repressor mutant, subunit A" then click on the link to "winged helix repressor DNA binding domain". Or, just enter "winged helix" into the search field. This subquery should match more than 500 coordinate entries.

- Click on the (+) button behind "Add search criteria" to add an additional query. Select the option "Structure Features"→"Macromolecule type". In the option menus that pop up, select "Contains Protein → Yes", "Contains DNA → Yes""Contains RNA → Ignore" "Contains DNA/RNA hybrid → Ignore". This selects files that contain Protein-DNA complexes.

- Check the box below this subquery to "Remove Similar Sequences at 90% identity" and click on "Submit Query". This query should retrieve more than 90 complexes.

- Scroll down to the beginning of the list of PDB codes and locate the "Generate reports" menu. Under the heading Custom reports select Image collage. This is a fast way to obtain an overview of the structures that have been returned. First of all you may notice that in fact not all of the structures are really different, despite selecting only to retrieve dissimilar sequences. This appears to be a deficiency of the algorithm. But you can also easily recognize how in most of the the structures the recognition helix inserts into the major groove of B-DNA (eg. 1BC8, 1CF7). There is one exception: the structure 1DP7 shows how the human RFX1 protein binds DNA in a non-canonical way, through the beta-strands of the "wing". This is interesting since it suggests there is more than one way for winged helix domains to bind to DNA. We can therefore use structural superposition of your homology model and two of the winged-helix proteins to decide whether the canonical or the non-canonical mode of DNA binding seems to be more plausible for Mbp1 orthologues.

- Follow the procedure outlined above, from a CATH entry page up to viewing a Collage (or alternatively a tabular view) of the retrieved coordinate files. You can be maximally concise in your documentation for the procedure I have defined above, but I expect you to have spent enough time on this process to understand the key elements of the PDB's advanced search interface.

(4.2) Preparation and superposition of a canonical complex

The structure we shall use as a reference for the canonical binding mode is the Elk-1 transcription factor.

The 1DUX coordinate-file contains two protein domains and two B-DNA dimers in one asymmetric unit. For simplicity, you should delete the second copy of the complex from the PDB file. (Remember that PDB files are simply text files that can be edited.)

- Access the PDB and navigate to the 1DUX structure explorer page. Download the coordinates to your computer.

- Open the coordinate file in a text-editor and delete the coordinates for chains

D,EandF; you may also delete allHETATMrecords and theMASTERrecord. Save the file with a different name, e.g. 1DUX_monomer.pdb . - Open VMD and load your homology model. Turn off the axes, display the model as a Tube representation in stereo, and color it by Index. Then load your edited 1DUX file, display this coordinate set in a tube representation as well, and color it by ColorID in some color you like. It is important that you can distinguish easily which structure is which

- You could use the Extensions→Analysis→RMSD calculator interface to superimpose the two strutcures IF you would know which residues correspond to each other. Sometimes it is useful to do exactly that: define exact correspondences between residue pairs and superimpose according to these selected pairs. For our purpose it is much simpler to use the Multiseq tool (and the structures are simple and small enough that the STAMP algorithm for structural alignment can define corresponding residue pairs automatically). Open the multiseq extension window, select the check-boxes next to both protein structures, and open the Tools→Stamp Structural Alignment interface.

- In the "'Stamp Alignment Options'" window, check the radio-button for Align the following ... Marked Structures and click on OK.

- In the Graphical Representations window, double-click on all "NewCartoon" representations for both molecules, to undisplay them.

- You should now see a superimposed tube model of your homology model and the 1DUX protein-DNA complex. You can explore it, display side-chains etc. and study some of the details of how a transcription factor recognizes and binds to its cognate DNA sequence. However, remember that your model's side-chain orientations have not been determined experimentally but inferred from the template, and that the template's structure was determined in the absence of bound DNA ligand.

- Orient and scale your superimposed structures so that their structural similarity is apparent, and the recognition helix can be clearly seen inserting into the DNA major groove. Paste a copy of your image into your assignment. Remark briefly on which parts of the structure appear to superimpose best. Note whether this orientation of a B-DNA double-helix is a plausible model for DNA binding of your Mbp1 orthologue.

(4.2) Preparation and superposition of a non-canonical complex

The structure displaying a non-canonical complex between a winged-helix domain and its cognate DNA binding site is the human Regulatory Factor X.

Before we can work with this however, we have to fix an annoying problem caused by the way the PDB stores replicates in biological assemblies. The PDB generates additional chains as copies of the original and delineates them with MODEL and ENDMDL records, just like in a multi-structure NMR file. The chain IDs and the atom numbers are the same as the original. The PDB file thus contains the same molecule in two different orientations, not two independent molecules. This is an important difference regarding how such molecules are displayed by VMD. If you were to use the biological unit file of the PDB, VMD does not recognize that there is a second molecule present and displays only one. We have to edit the file to merge the two molecules by removing the MODEL and ENDMDL records - and while we're editing the file we'll also remove unneeded heteroatoms and the second copy of the protein chain (which we don't need, we need only the second B-DNA strand). But then we end up with residues that have exactly the same residue number in the same file. That won't work for visualization, since the program expects residue numbers to be unique, therefore we have to renumber the residues. Here's how:

- On the structure explorer page for 1DP7, select the option Download Files → Biological Assembly.

- Dowload, save and uncompress the file.

- Open the file in a text editor.

- Delete both

MODELand bothENDMDLrecords. - Also delete all

HETATMrecords forHOH,PEGandEDO, as well as the entire second protein chain and theMASTERrecord. The resulting file should only contain the DNA chain and its copy and one protein chain. Save the file with a new name. - Access the Whatif Web interface and click on Administration and Renumber a PDB File from 1. Upload your edited file, access the results and save the file.

- Open the renumbered file with VMD. You should see one protein chain and a B-DNA double helix. Switch to stereo viewing and spend some time to see how amazingly beautiful the complementarity between the protein and the DNA helix is (you might want to display chain P and chain D in separate representations and color the DNA chain by Position → Radial for clarity) ... in particular, appreciate how Arginine 76 interacts with the base of Guanine 92!

- Then clear all molecules

- In VMD, open Extensions→Analysis→MultiSeq. When you run MultiSeq for the first time, you will be asked for a directory in which to store metadata. You can use the default, or a directory of your choice; you may subsequently skip all steps that ask you to install "required" databases locally since we will not need them for this task.

- A window will appear - the MultiSeq window - it contains the sequence of the APSES domain you are visualizing. MultiSeq will also generate an additional cartoon representation of the structure. Choose File→Import Data, browse to your directory and load:

- Your model;

- The 1DUX complex;

- The 1DP7 complex.

- Mark all three protein chains by selecting the checkbox next to their name and run the STAMP structural alignment.

- In the graphical representations window, double-click on the cartoon representations that multiseq has generated to undisplay them, also undisplay the Tube representation of 1DUX. Then create a Tube representation for 1DP7, and select a Color by ColorID (a different color that you like). The resulting scene should look similar to the one you have created above, only with 1DP7 in place of 1DUX and colored differently.

- Orient and scale your superimposed structures so that their structural similarity is apparent, the orientation is similar to the scene generated above and the 1DP7 "wing" can be clearly seen inserting into the DNA major groove. Paste a copy of your image into your assignment. Remark briefly on which parts of the structure appear to superimpose best. Note whether this orientation of a B-DNA double-helix is a plausible model for DNA binding of your Mbp1 orthologue.

(4.3) Coloring by conservation

With the superimposed coordinates, you can begin to get a sense whether either or both binding modes could be appropriate for a protein-DNA complex in your Mbp1 orthologue. But these are geometrical criteria only, and the protein in your species may be flexible enough to adopt a different conformation in a complex, and different again from your model. A more powerful way to analyze such hypothetical complexes is to look at conservation patterns. With VMD, you can import a sequence alignment into the MultiSeq extension and color residies by conservation. The protocol below assumes

- You have prealigned the reference Mbp1 proteins with your species' Mbp1 orthologue;

- You have saved the alignment in a CLUSTAL format.

You can use Jalview or any other MSA server to do so. You can even do this by hand - there should be few if any indels and the correct alignment is easy to see.

- Load the Mbp1 APSES alignment into MultiSeq.