Difference between revisions of "Lecture 02"

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

| (19 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | <!-- div style="padding: 5px; background: #FF4560; border:solid 2px #000000;"> | ||

| + | '''Update Warning!''' | ||

| + | This page has not been revised yet for the current term. Some of the slides may be reused, but please consider the page as a whole out of date as long as this warning appears here. | ||

| + | </div --> | ||

| + | | ||

| + | |||

| + | | ||

| + | |||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

<small>[[Lecture_01|(Previous lecture)]] ... [[Lecture_03|(Next lecture)]]</small> | <small>[[Lecture_01|(Previous lecture)]] ... [[Lecture_03|(Next lecture)]]</small> | ||

| Line 4: | Line 12: | ||

==The Sequence Abstraction== | ==The Sequence Abstraction== | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ;What you should take home from this part of the course: | |

| − | * Exercises | + | *Know the one-letter code and key properties of all 20 proteinogenic aminoacids; |

| − | * | + | *Understand the benefits and limitations of the sequence abstraction; |

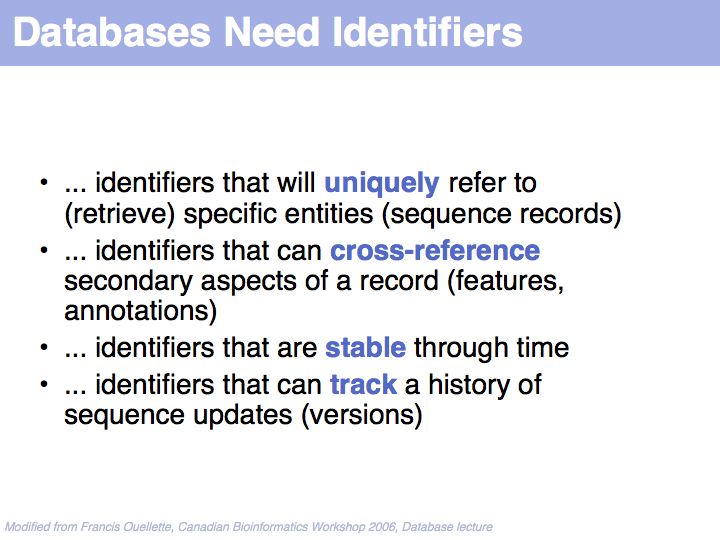

| + | *Recognize common sequence identifiers, utilize them confidently; | ||

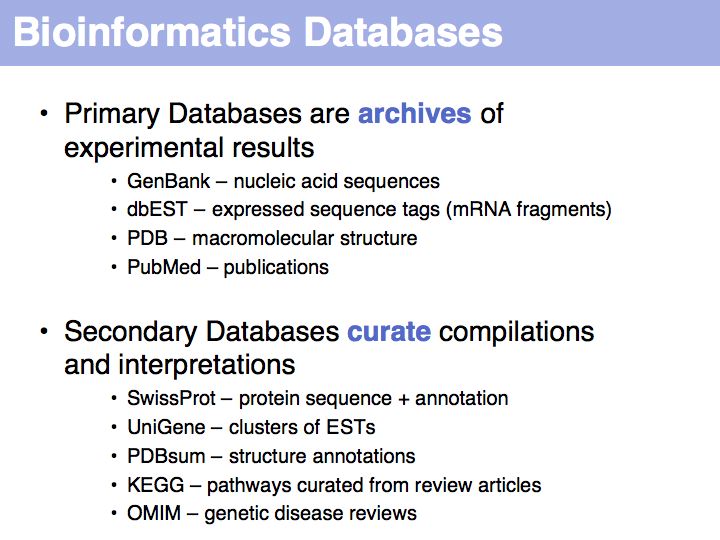

| + | *Know about the contents of key sequence databases; | ||

| + | *Be able to retrieve sequence data; | ||

| + | *Know about and confidently use the fields in GenBank and GenPept records. | ||

| + | | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Links summary: | ||

| + | *[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IUPAC IUPAC] (Wikipedia) | ||

| + | *[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adenine '''a'''denine], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cytosine '''c'''ytosine], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guanine '''g'''uanine], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thymine '''t'''hymine] (Wikipedia) | ||

| + | *[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simplified_Molecular_Input_Line_Entry_Specification SMILES] (Wikipedia) | ||

| + | *[http://speedy.embl-heidelberg.de/aas/ Rob Russel's Amino Acid Pages] | ||

| + | *[http://www.geneontology.org/ GO (Gene Ontology)] | ||

| + | *[http://obofoundry.org/ Open Biology Ontologies] | ||

| + | *[[Glossary#FASTA_format|FASTA format]] | ||

| + | *[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/GenbankOverview.html Genbank Overview] | ||

| + | *[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/viewer.fcgi?db=nuccore&id=4594 A GenBank] record example | ||

| + | *[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/viewer.fcgi?db=protein&id=6320957 A GenPept] record example | ||

| + | *[http://www.pir.uniprot.org/cgi-bin/upEntry?id=SWI4_YEAST A UniProt] record example | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query/static/help/entrez_tutorial_BIB.pdf Entrez tutorial (pdf)] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Exercises | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Find a protein that contains a '''selenocysteine''' residue (e.g. human glutathione peroxidase). Check the Genbank record to see how this residue is represented in the sequence and in the record. Find and compare the corresponding SwissProt record. | ||

| + | *Find a secreted protein such as ''E. coli'' '''beta-lactamase'''. Look into the Genbank record whether you can identify the signal-peptide that is post-translationally removed. Find the corresponding SwissProt entry and look for the annotation. | ||

| + | *Human mitochondrial proteins are translated according to a different genetic code from human nuclear proteins. Looking at the CDS of mitochondrial Cytochrome B ('''NC_001807'''), how would you know? | ||

| + | |||

| + | | ||

| + | | ||

==Lecture Slides== | ==Lecture Slides== | ||

======Slide 001====== | ======Slide 001====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s001.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 001]] | + | [[Image:L02_s001.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 001<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 002====== | ======Slide 002====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s002.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 002]] | + | [[Image:L02_s002.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 002<br> |

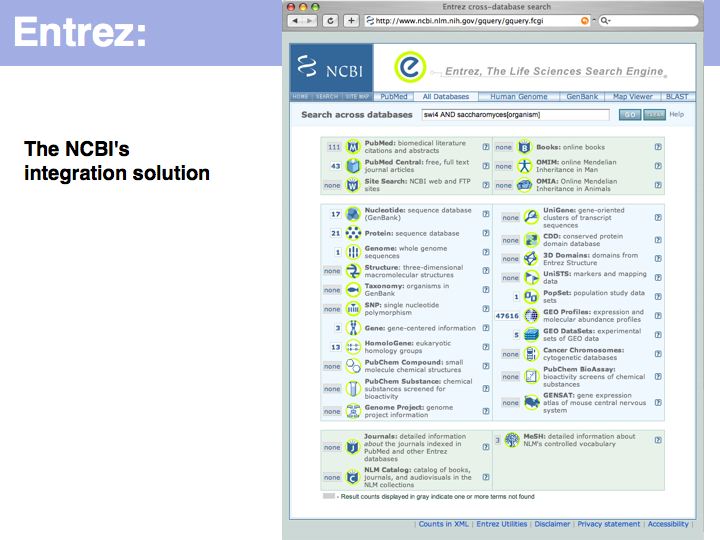

| + | Deconstruct this statement: first, we need to consider what it means to compute. Then we need to consider the best representations. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

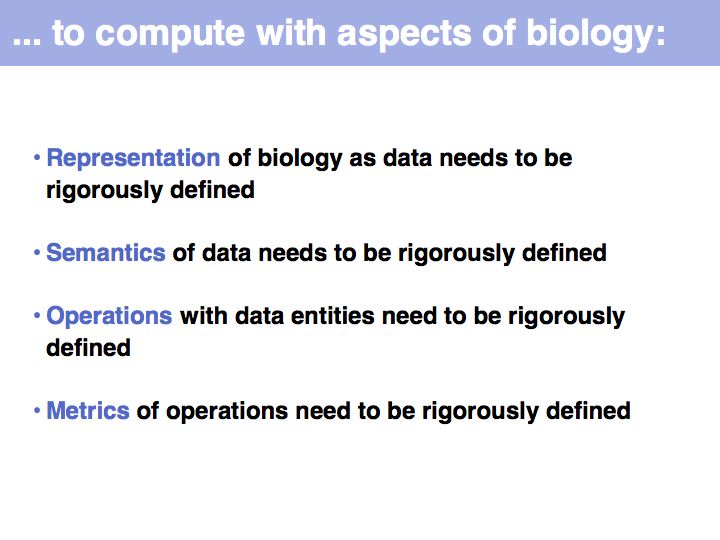

======Slide 003====== | ======Slide 003====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s003.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 003]] | + | [[Image:L02_s003.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 003<br> |

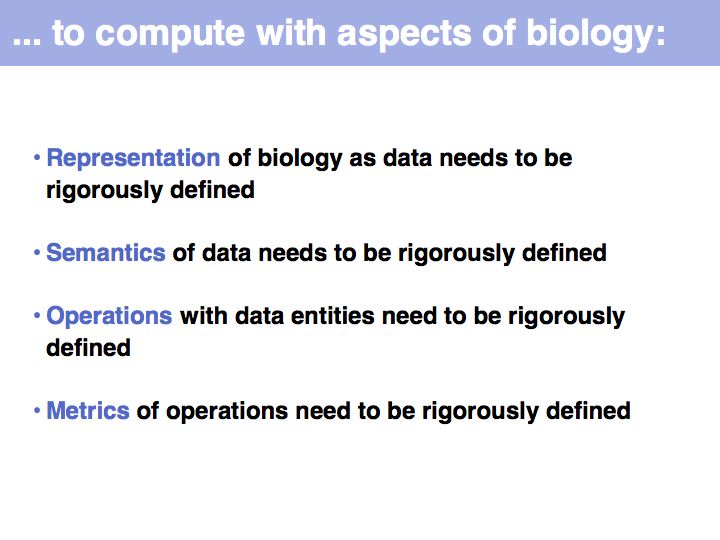

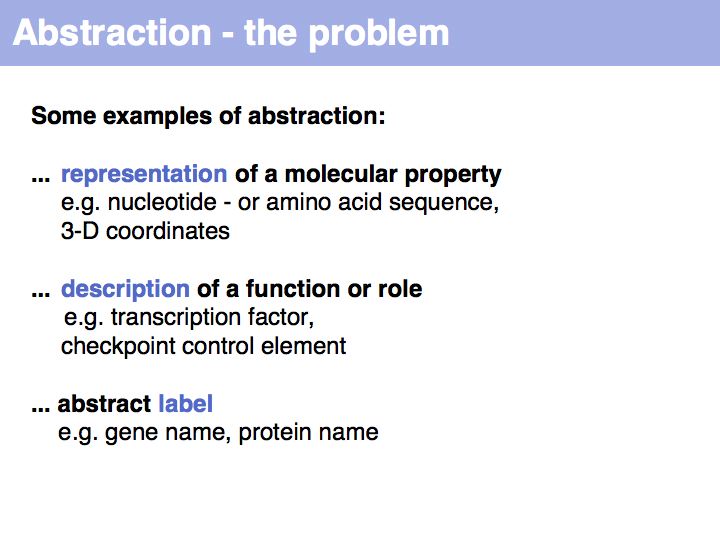

| + | In order to make biology computable, we have to clarify the concepts we are working with. This is useful even beyond the requirements of bioinformatics. It is an exercise in clarifying the conceptual foundations of biology itself. In many instances, definitions in current, common use are deficient, either because our current state of knowledge has gone beyond the original ideas we were trying to subsume with a term (e.g. '''gene''', or '''pathway'''), or because an inconsistent formal and colloquial meaning of terms lead to ambiguities (e.g. '''function'''), or because the technical meaning of terms is poorly understood and generally misused (e.g. '''homology'''). | ||

| + | ]] | ||

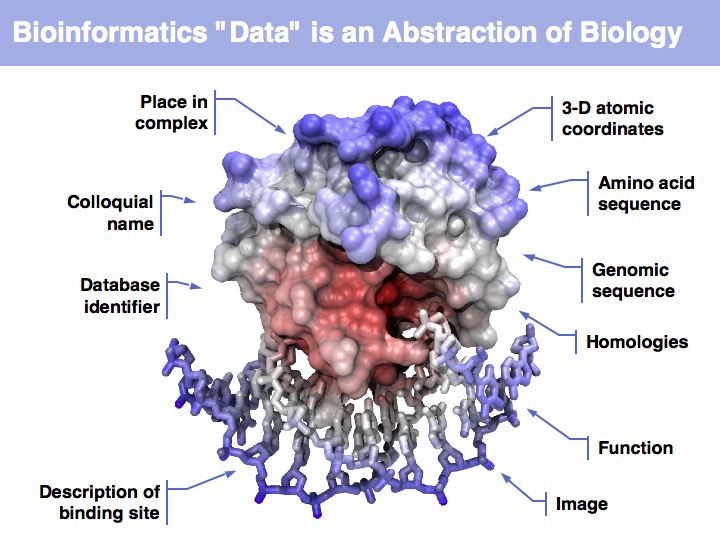

======Slide 004====== | ======Slide 004====== | ||

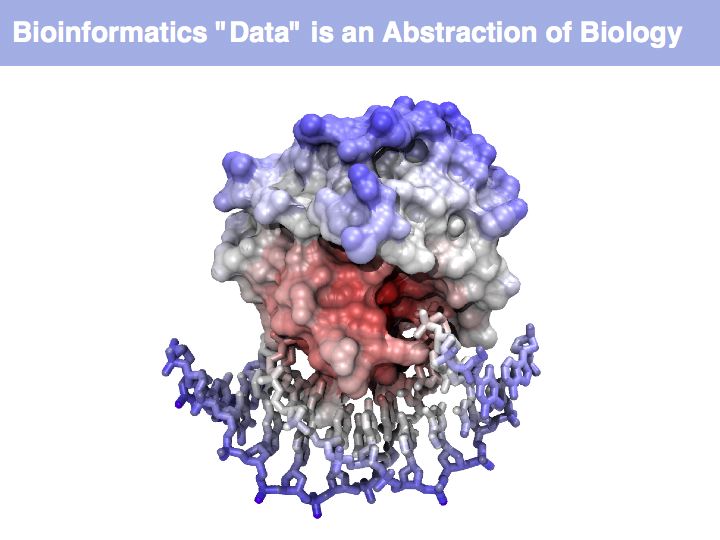

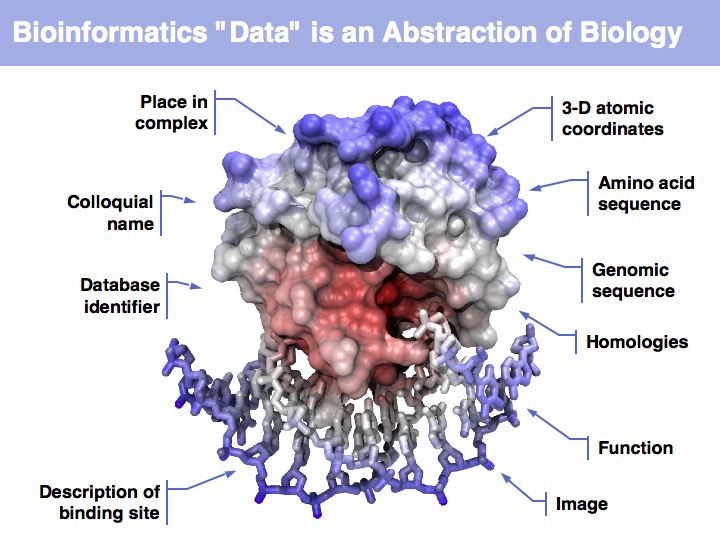

| − | [[Image:L02_s004.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 004]] | + | [[Image:L02_s004.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 004<br> |

| + | Think about the following question: this image representis a particular biomolecule. '''What is the best abstraction ?''' | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 005====== | ======Slide 005====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s005.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 005]] | + | [[Image:L02_s005.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 005<br> |

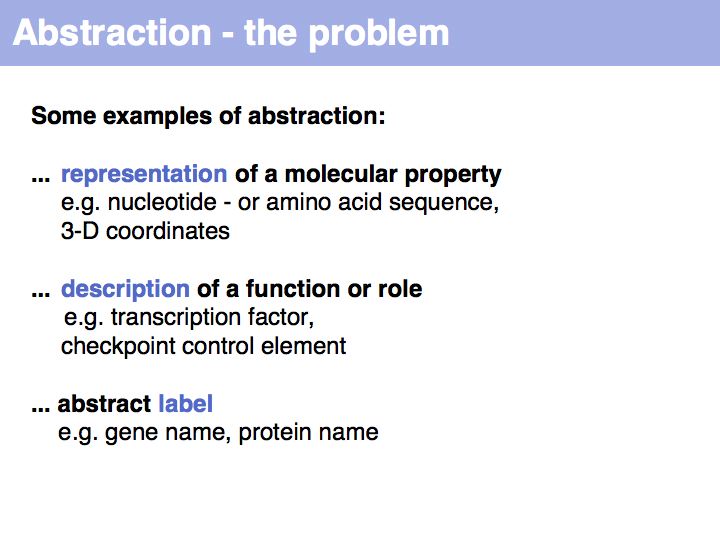

| + | Asking about '''the best''' is an ill-posed question if the purpose is not specified. '''The best for what?''' There are many possible abstractions, each serving different purposes. Each of the abstractions above can serve as a representation of the biomolecule, each one emphasizes a different perspective and can serve a different purpose. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 006====== | ======Slide 006====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s006.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 006]] | + | [[Image:L02_s006.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 006<br> |

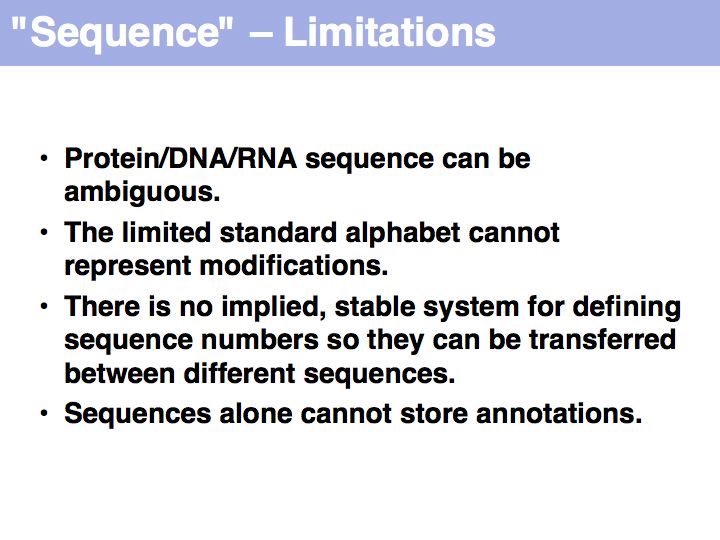

| + | Working with abstractions implies we are no longer manipulating the '''biological entity''', but it's representation.This distinction becomes crucial, when we start computing with representations to infer facts about the original entities! Inferences must be related back to biology! Common problems include that the abstraction may not be rich enough to capture the property we are investigating (e.g. one-letter sequence codes cannot represent amino acid modifications or sequence numbers), or the abstraction may be ambiguous (e.g. one protein may have more than one homologue in a related organism, thus the relationship between gene IDs is ambiguous) or the abstraction may not be unique (e.g. one protein may have more than one function, the same protein name may refer to unrelated proteins in different species). | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | |||

======Slide 007====== | ======Slide 007====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s007.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 007]] | + | [[Image:L02_s007.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 007<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 008====== | ======Slide 008====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s008.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 008]] | + | [[Image:L02_s008.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 008<br> |

| + | Nucleic acids can form heterocopolymers as DNA or RNA, thus their structural formula can be described (to a close approximation) simply by listing the nucleotide bases in a defined order. A one-letter code has been defined as a shorthand notation for this. By convention, DNA or RNA sequence is written in the direction from the bond with the 5' carbon of the ribose (or deoxyribose), to the bond with the 3'-carbon. Since the 5'-carbon carries a free 5'-phosphate at the terminus of the polynucleotide and the 3'-carbon carries a free OH, this direction happens to be the same direction that nucleic acid polymers are replicated by the DNA-polymerase: a phosphate of a single nucleotide is attached to the free -OH of the polynucleotide. This direction is also the direction of transcription of the RNA polymerase (for the same reason) and (incidentally) the direction of translation by the ribosome. Due to base-pair complementarity, only one strand of a double stranded sequence needs to be recorded since the sequence of the complementary strand is implied: it is simply the reverse complement. The one letter abbreviations are defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry ([http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IUPAC IUPAC]) as follows:</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt></tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> A = [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adenine '''a'''denine]</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> C = [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cytosine '''c'''ytosine]</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> G = [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guanine '''g'''uanine]</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> T = [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thymine '''t'''hymine]</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> R = G A (pu'''r'''ine)</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> Y = T C (p'''y'''rimidine)</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> K = G T ('''k'''eto)</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> M = A C (a'''m'''ino)</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> S = G C ('''s'''trong bonds)</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> W = A T ('''w'''eak bonds)</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> B = G T C (not '''A''')</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> D = G A T (not '''C''')</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> H = A C T (not '''G''')</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> V = G C A (not '''T''')</tt><br> | ||

| + | <tt> N = A G C T (a'''n'''y)</tt> | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | |||

======Slide 009====== | ======Slide 009====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s009.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 009]] | + | [[Image:L02_s009.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 009<br> |

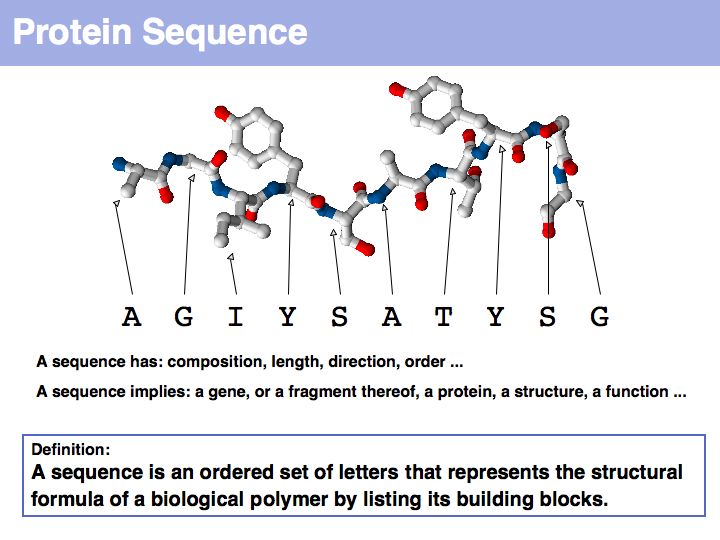

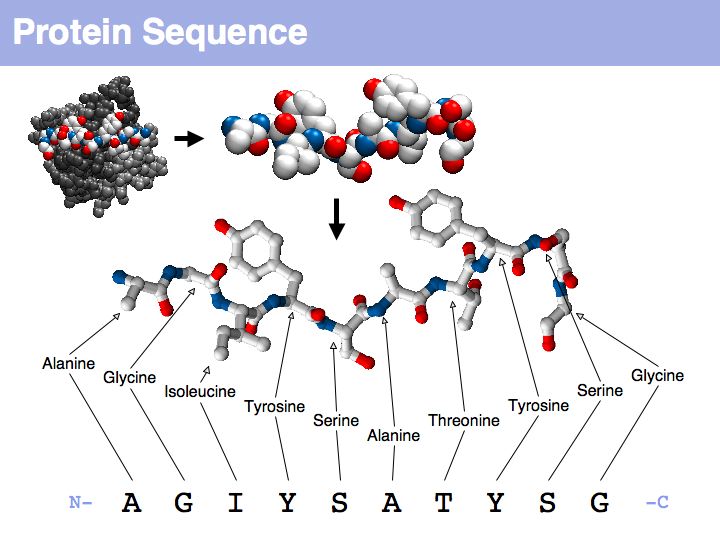

| + | Proteins are amino acid heterocopolymers, thus their structural formula can be described (to a close approximation) simply by listing their constituent amino acid residues '''in a defined order'''. The one-letter code is a shorthand notation for this. By convention, protein sequence is written from aminoterminus (N-) to carboxyterminus (C-). This happens to be the same direction in which the protein is synthesized on the ribosome. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 010====== | ======Slide 010====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s010.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 010]] | + | [[Image:L02_s010.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 010<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 011====== | ======Slide 011====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s011.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 011]] | + | [[Image:L02_s011.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 011<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 012====== | ======Slide 012====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s012.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 012]] | + | [[Image:L02_s012.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 012<br> |

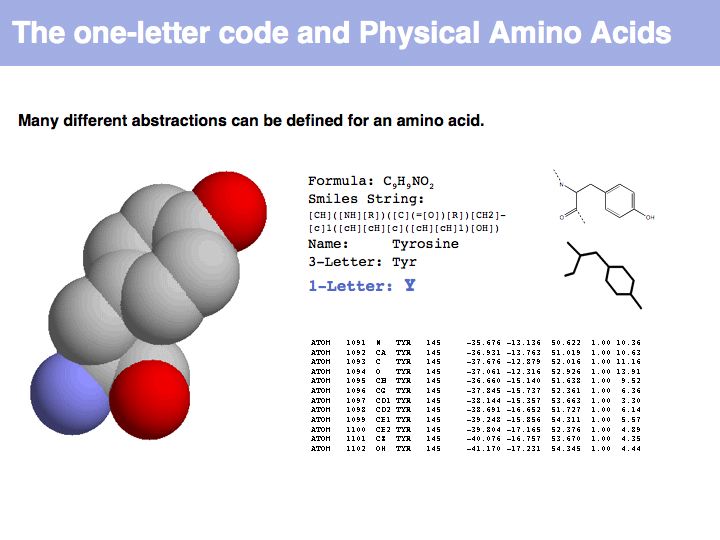

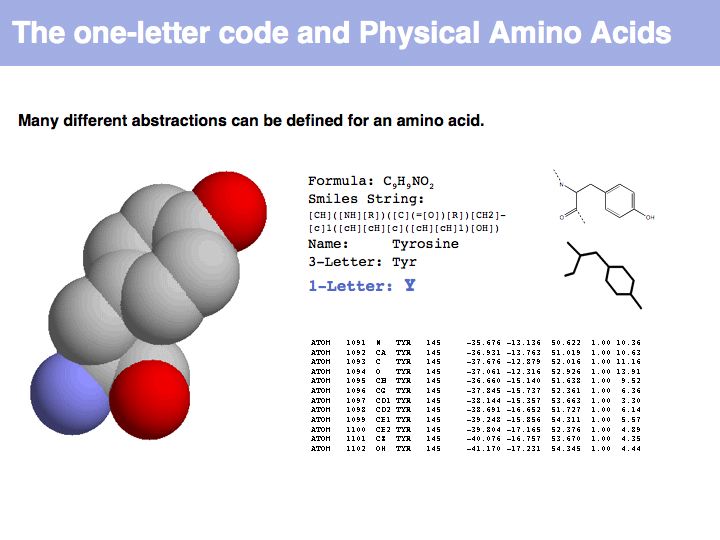

| + | An amino acid is a molecule. A number of abstractions are in common use for this molecule: its chemical formula simply describes the elemental composition, a so called [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simplified_Molecular_Input_Line_Entry_Specification ''SMILES''] string (''see also [http://www.daylight.com/dayhtml/doc/theory/theory.smiles.html here]'') captures bonding topology as well, its information is equivalent to a chemical graph. A set of records of 3D coordinates can describe the three-dimensional conformation, this can in turn be displayed in a number of different image options - like a simple line drawing or a set of spheres, color coded by element, with relative sizes corresponding to the elements' Van der Waals radii. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 013====== | ======Slide 013====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s013.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 013]] | + | [[Image:L02_s013.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 013<br> |

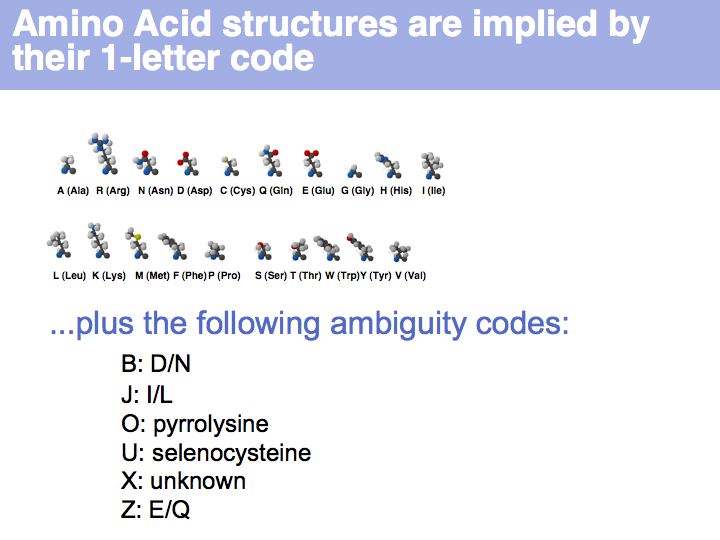

| + | ... see IUPAC | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 014====== | ======Slide 014====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s014.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 014]] | + | [[Image:L02_s014.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 014<br> |

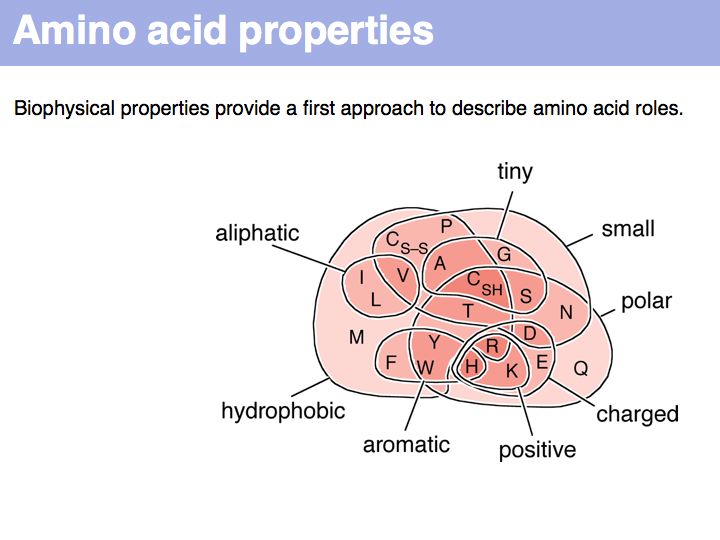

| + | A Venn diagram of biophysical amino acid properties. Of course, the '''precise''' role of a particular amino acid depends on its context in a folded protein.]] | ||

| + | |||

======Slide 015====== | ======Slide 015====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s015.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 015]] | + | [[Image:L02_s015.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 015<br> |

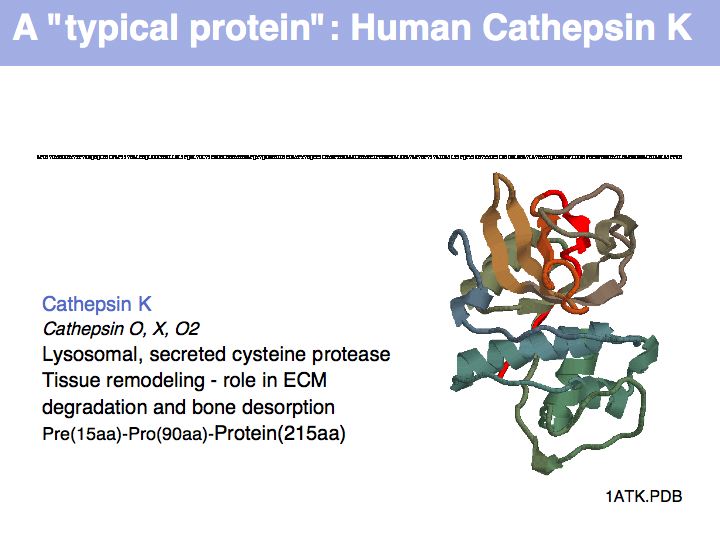

| + | The physicochemical properties of amino acids determines their role in e.g. a folded protein structure. For example, consider the amino acid distribution in a typical enzyme, such as cathepsin K (1ATK). | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 016====== | ======Slide 016====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s016.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 016]] | + | [[Image:L02_s016.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 016<br> |

| + | Hydrophobic amino acids - the group FAMILYVW - are found predominantly in the core of a protein, small amino acids such as GASC are often found in turns, charged amino acid sidechains - (+):KRH and (-)DE - are almost exclusively found on the surface; the energetic requirements for desolvation of the sidechain makes their incorporation into the core unfavourable. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 017====== | ======Slide 017====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s017.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 017]] | + | [[Image:L02_s017.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 017<br> |

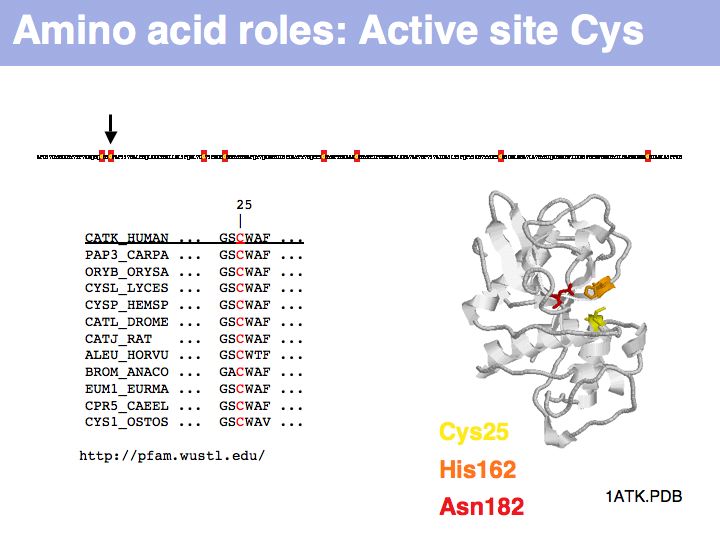

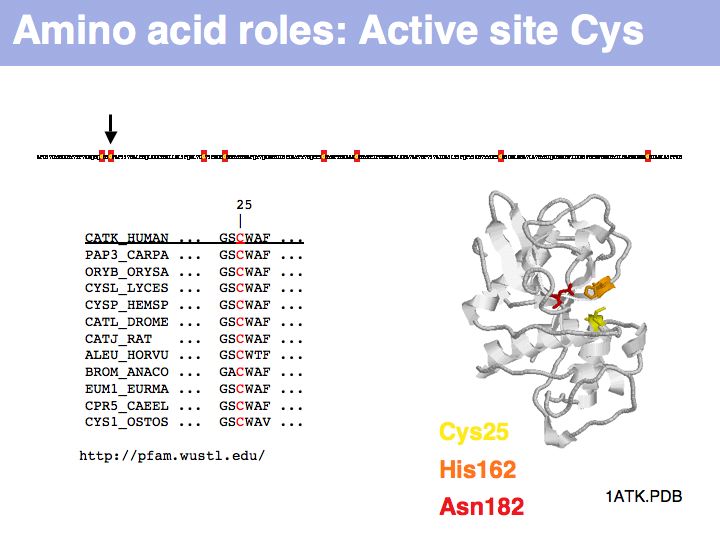

| + | Cysteine can take on a number of different roles, depending on its context. Here, cysteine forms part of the active site, it is the nucleophile in the catalytic triad C-H-N; cathepsin is thuss an example of a cysteine-protease. This particular cysteine is absolutely conserved in related proteins. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 018====== | ======Slide 018====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s018.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 018]] | + | [[Image:L02_s018.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 018<br> |

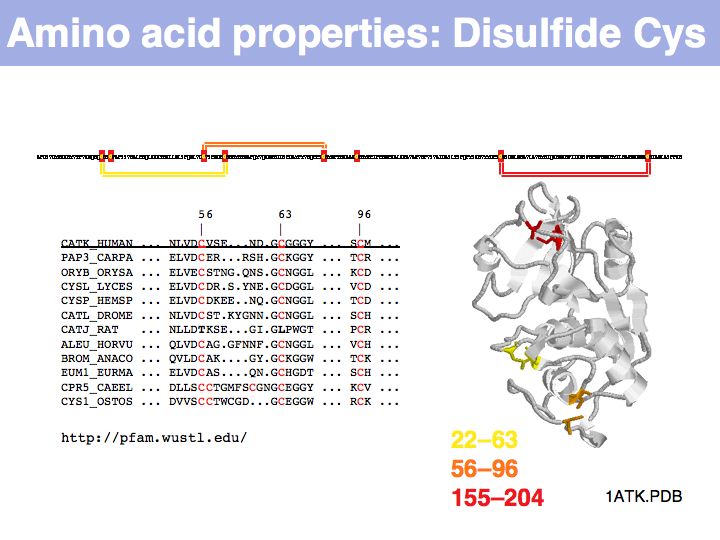

| + | In secreted proteins '''only''', cysteine often forms structural disulfide bridges in which two thiol groups oxidize to a covalent disulfide bond. These cysteines usually are highly conserved. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 019====== | ======Slide 019====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s019.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 019]] | + | [[Image:L02_s019.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 019<br> |

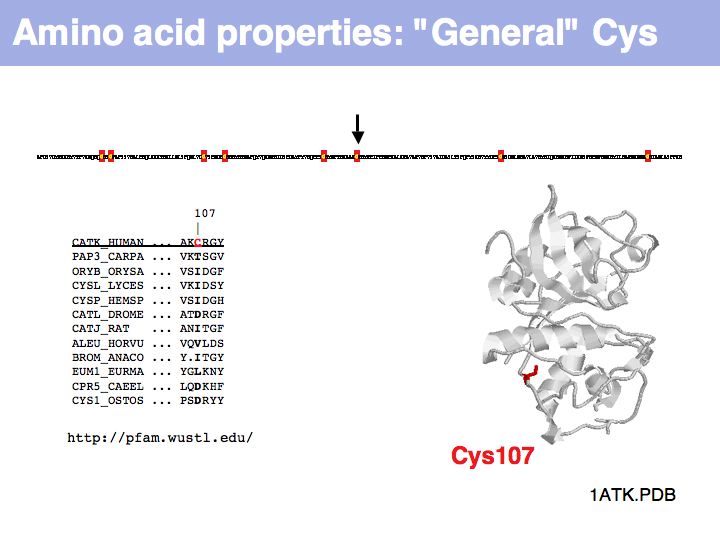

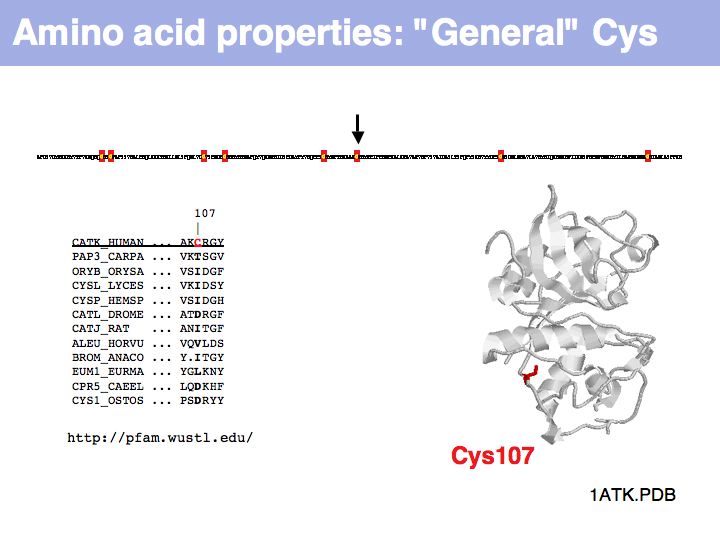

| + | Cysteine can also be found in a very general role, simply as a somewhat polar, small residue. This general role is infrequent in secreted proteins since it can interfere with the formation of the correct disulfide topology and generally makes the protein sensitive to oxidation. Such cysteines are poorly conserved in related proteins. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 020====== | ======Slide 020====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s020.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 020]] | + | [[Image:L02_s020.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 020<br> |

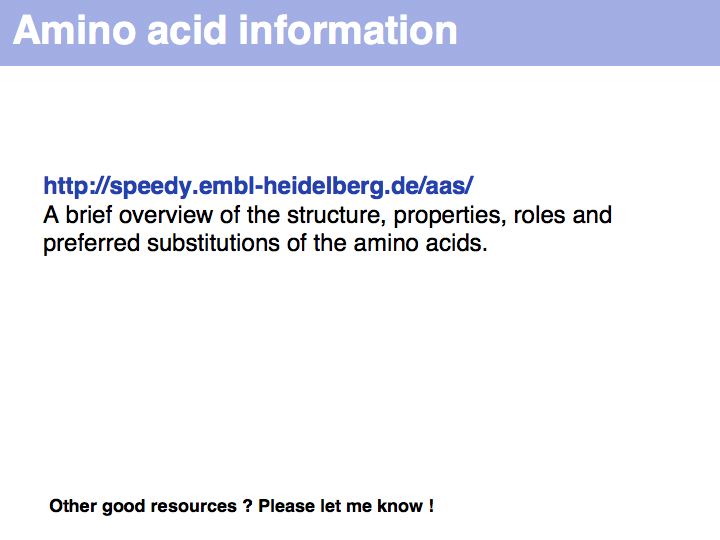

| + | Sequence is the most important abstraction in biology; you need to know your amino acids in order to relate a sequence back to the biopolymer. Required knowledge is: the '''structural formula''', the '''one-''' and '''three- letter codes''' and key properties (such as charge, relative size, polarity) for all 20 proteinogenic amino acids. A resource that summarizes amino acid properties is at http://speedy.embl-heidelberg.de/aas/ | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | |||

======Slide 021====== | ======Slide 021====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s021.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 021]] | + | [[Image:L02_s021.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 021<br> |

| + | In [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romeo_and_Juliet Shakespeare's classic tragedy] of romantic love and family allegiance, Juliet encapsulates the play's central struggle in this phrase by claiming that Romeo's family name is an artificial and meaningless convention. Just like in the world of the sequence abstraction, this is only partially true: the problems are not just based in the fact that Romeo is '''called''' a Montague, but that he '''is''' in fact a member of that family. Even if a ''Thing'' does not change if it's abstract label changes, such labels rarely exist in isolation: other ''Things'' might be referred to by the same label and changing one changes the composition of the entire set. (Or, to remain with our example, as soon as Romeo renounces his name and thus his family, the family would be no longer the same.) Even worse - and this is something we encounter every day in bioinformatics - if identifiers are not stable over time, cross-references to that identifier fail. If you decide you'll call a rose a skunk, people would become very confused. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | |||

======Slide 022====== | ======Slide 022====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s022.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 022]] | + | [[Image:L02_s022.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 022<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 023====== | ======Slide 023====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s023.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 023]] | + | [[Image:L02_s023.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 023<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 024====== | ======Slide 024====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s024.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 024]] | + | [[Image:L02_s024.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 024<br> |

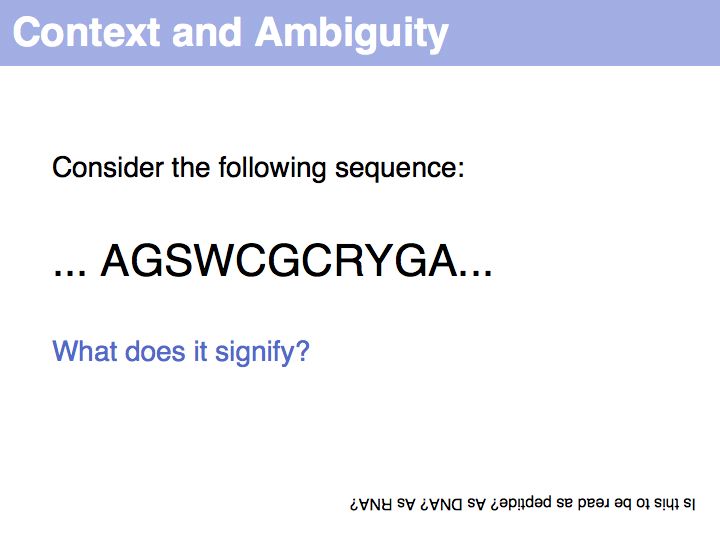

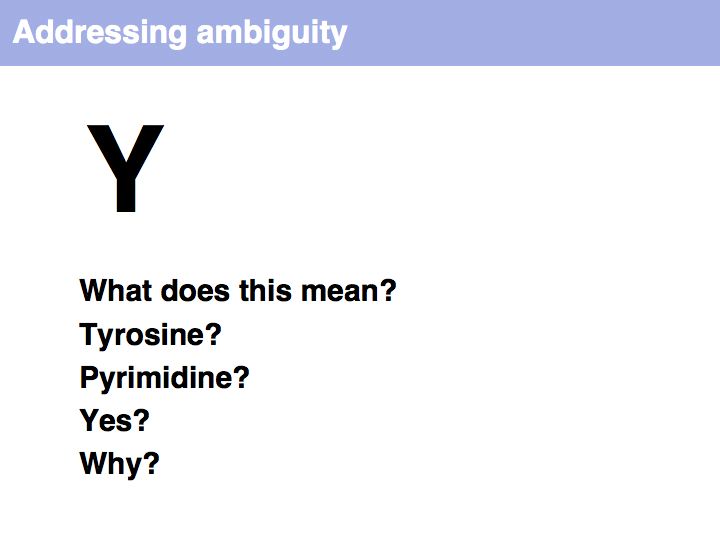

| + | Some ambiguity can only be resolved if the context of the representation is specified. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 025====== | ======Slide 025====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s025.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 025]] | + | [[Image:L02_s025.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 025<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 026====== | ======Slide 026====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s026.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 026]] | + | [[Image:L02_s026.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 026<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 027====== | ======Slide 027====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s027.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 027]] | + | [[Image:L02_s027.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 027<br> |

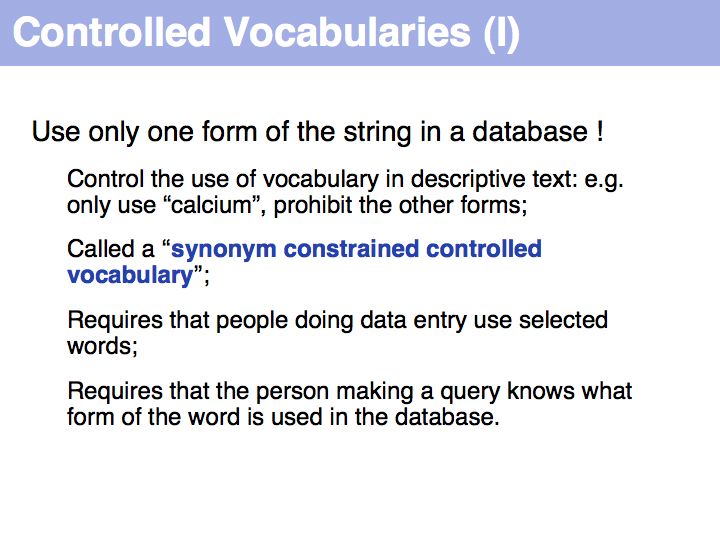

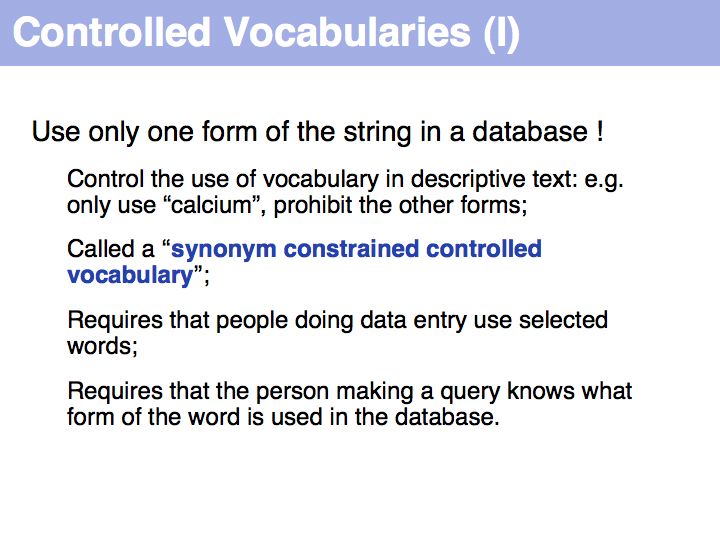

| + | Often synonym constrained controlled vocabularies are presented as option lists on Web forms. If the CV is too long for this approach to be practical, defining the correct form becomes a challenge. In well engineered databases a lot of effort is spent on this task; typically a large dictionary of synonym mappings is employed in some form. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 028====== | ======Slide 028====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s028.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 028]] | + | [[Image:L02_s028.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 028<br> |

| + | NB. The situation that a unique property of an entity can be concisely described is the ideal case: in that case the identifier captures the most fundamental aspect of the molecule. For calcium, the element does not just '''have''' the atomic number 20, it '''is''' the element with 20 protons. Similarly oxytocin does not just '''have''' the sequence CYIQNCPLG, it '''is''' the peptide with that sequence. However, these are favourable exceptions and more commonly unique, abstract labels - such as '''identifiers''' - have to be defined. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 029====== | ======Slide 029====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s029.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 029]] | + | [[Image:L02_s029.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 029<br> |

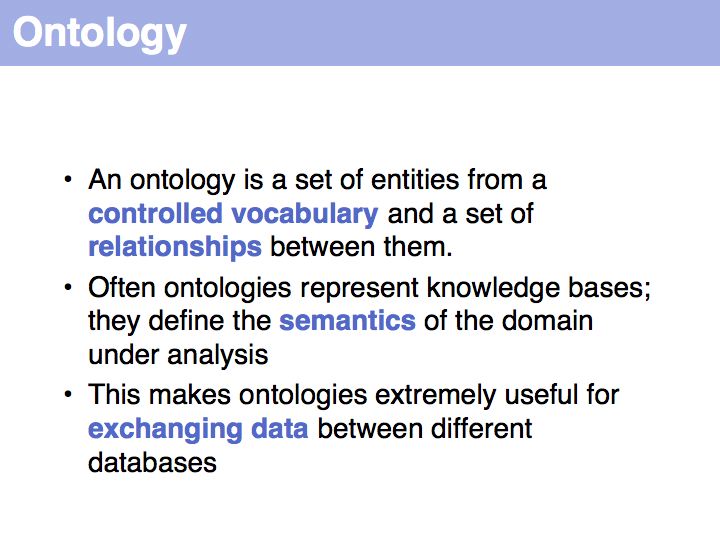

| + | Read more about the [http://www.geneontology.org/ Gene Ontology] project and [http://obofoundry.org/ the Open Biology Ontologies]. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 030====== | ======Slide 030====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s030.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 030]] | + | [[Image:L02_s030.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 030<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 031====== | ======Slide 031====== | ||

| − | + | <small>''(deleted)''</small> | |

| + | |||

======Slide 032====== | ======Slide 032====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s032.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 032]] | + | [[Image:L02_s032.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 032<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 033====== | ======Slide 033====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s033.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 033]] | + | [[Image:L02_s033.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 033<br> |

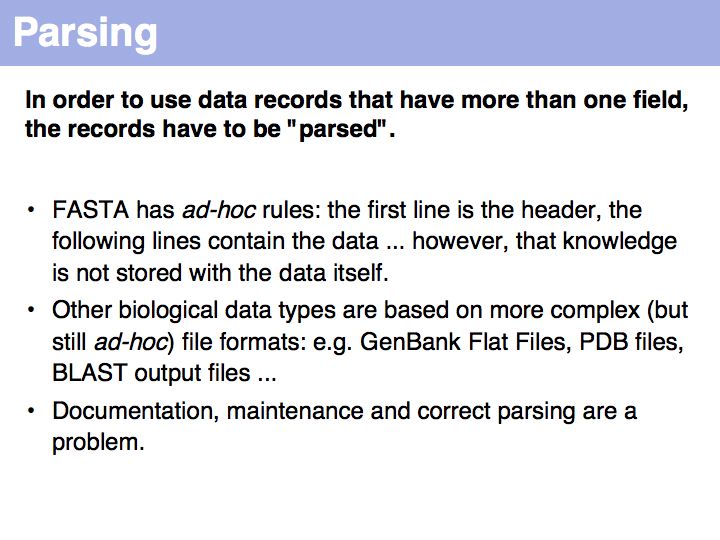

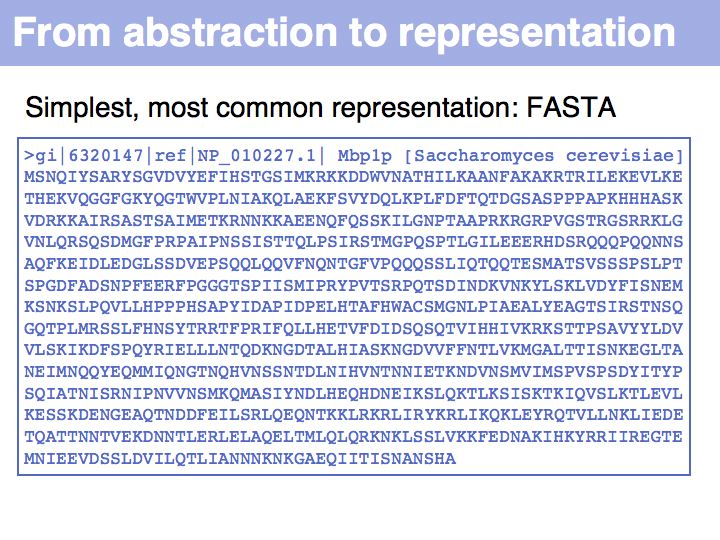

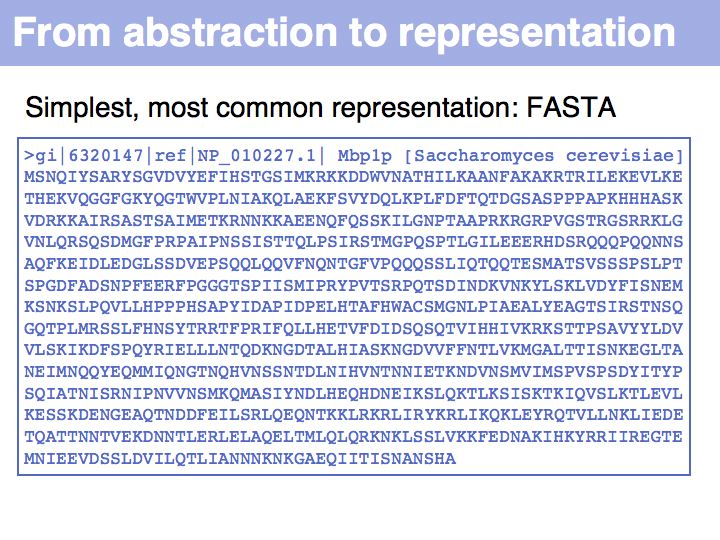

| + | Read more about the [[Glossary#FASTA_format|FASTA format]]. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 034====== | ======Slide 034====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s034.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 034]] | + | [[Image:L02_s034.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 034<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 035====== | ======Slide 035====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s035.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 035]] | + | [[Image:L02_s035.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 035<br> |

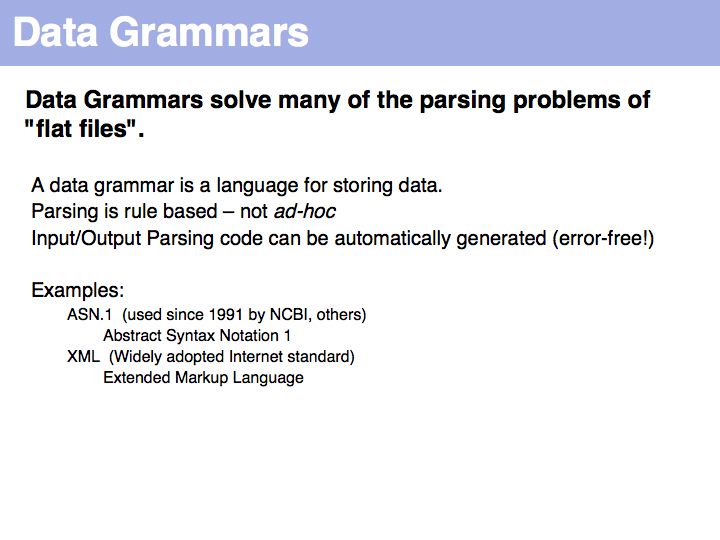

| + | Just like in human language, rigourous syntactical rules enforce that you can't use bad grammar and get away with it. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | |||

======Slide 036====== | ======Slide 036====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s036.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 036]] | + | [[Image:L02_s036.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 036<br> |

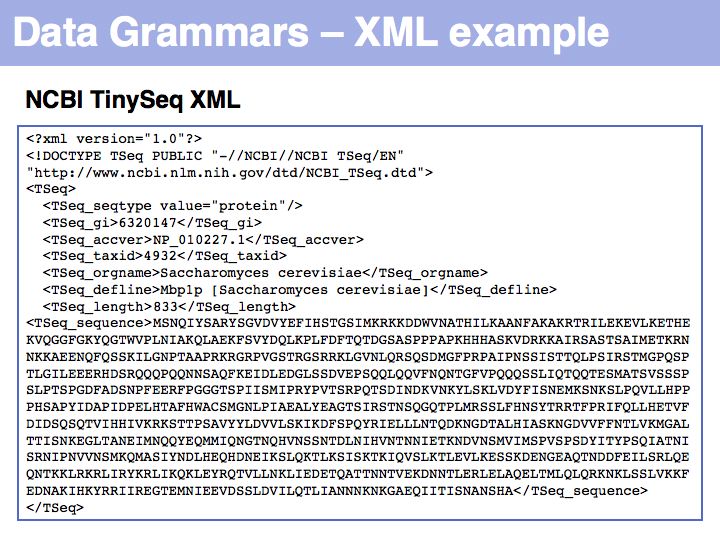

| + | XML formatted files are human readable - ''in principle''. The abundance of tags can make this challenging in practice. The loss of readability is a trade-off for the gain in rigour. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 037====== | ======Slide 037====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s037.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 037]] | + | [[Image:L02_s037.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 037<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 038====== | ======Slide 038====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s038.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 038]] | + | [[Image:L02_s038.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 038<br> |

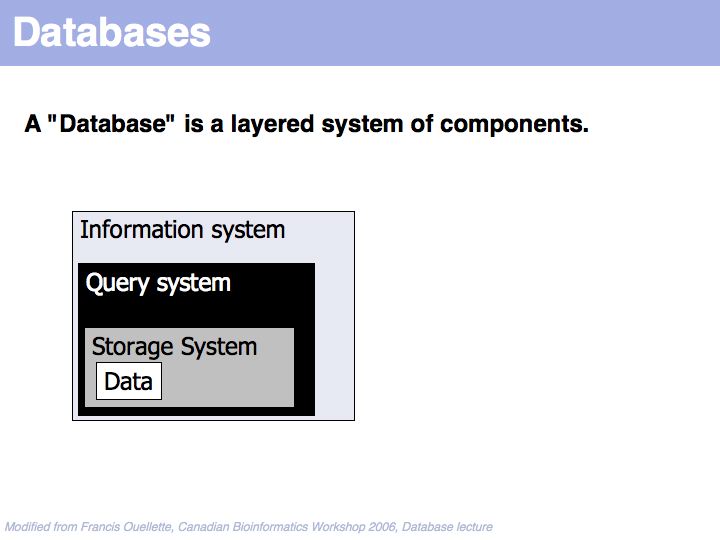

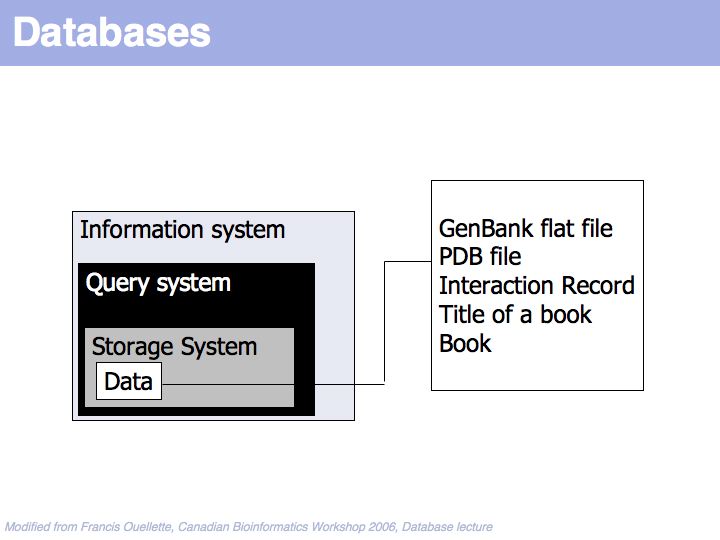

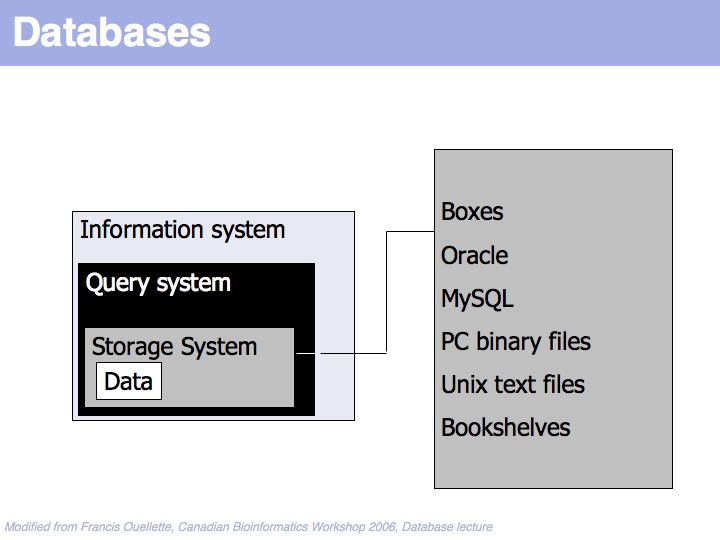

| + | A "Database" is much more than just the data it contains. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 039====== | ======Slide 039====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s039.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 039]] | + | [[Image:L02_s039.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 039<br> |

| + | At the core of the database is the data and of course the data should be the primary focus of attention of the database providers. Issues are the correctness of the data, mechanisms to validate and maintain records, frequency of updates, consistency etc. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 040====== | ======Slide 040====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s040.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 040]] | + | [[Image:L02_s040.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 040<br> |

| + | Data is stored in some storage system. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 041====== | ======Slide 041====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s041.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 041]] | + | [[Image:L02_s041.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 041<br> |

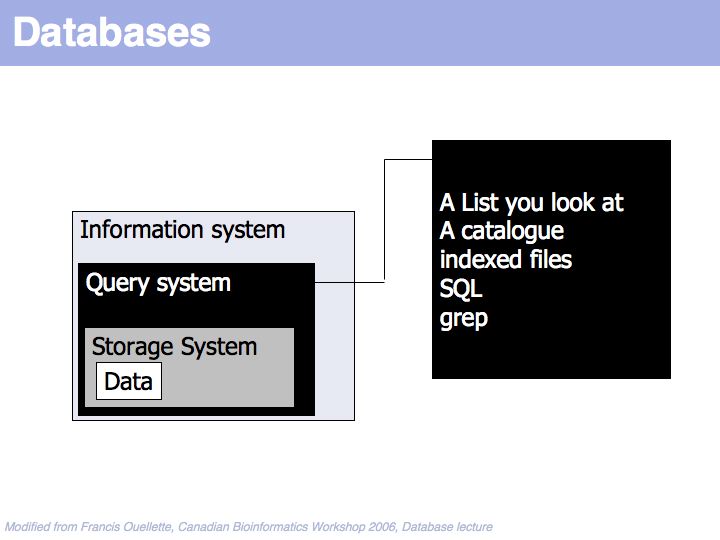

| + | Data is found through some query system. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 042====== | ======Slide 042====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s042.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 042]] | + | [[Image:L02_s042.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 042<br> |

| + | Storage resources, query and maintenance functions, and meta-information services are all united into a common interface that is presented to the user. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 043====== | ======Slide 043====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s043.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 043]] | + | [[Image:L02_s043.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 043<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 044====== | ======Slide 044====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s044.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 044]] | + | [[Image:L02_s044.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 044<br> |

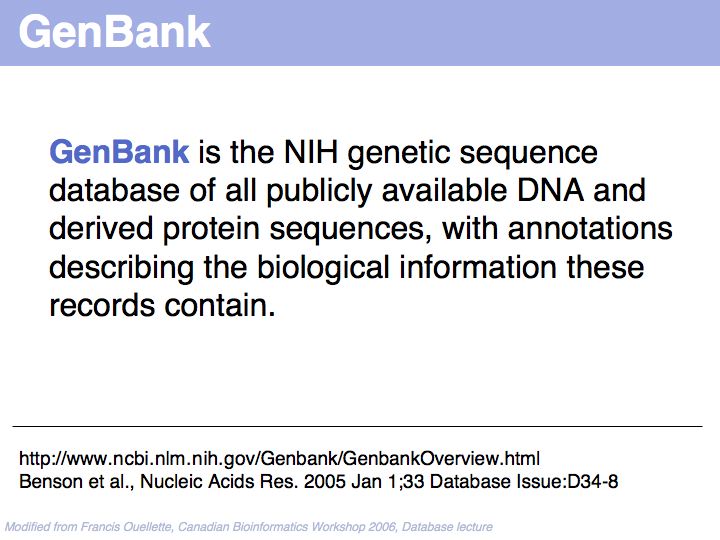

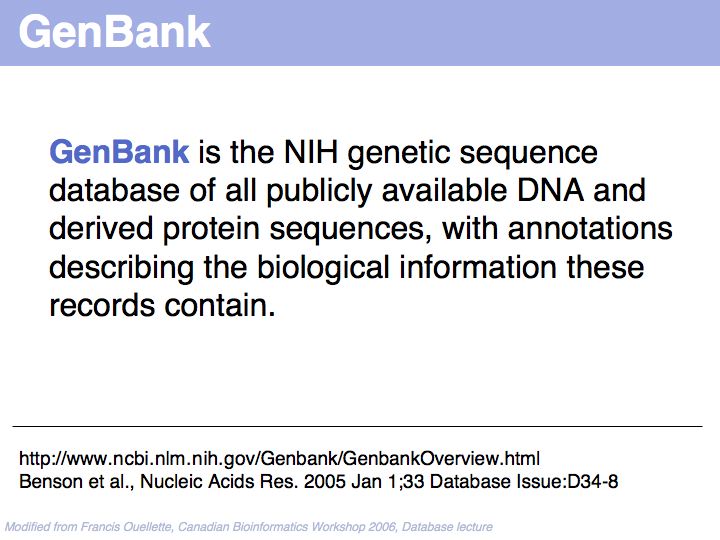

| + | see: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/GenbankOverview.html | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | |||

======Slide 045====== | ======Slide 045====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s045.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 045]] | + | [[Image:L02_s045.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 045<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 046====== | ======Slide 046====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s046.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 046]] | + | [[Image:L02_s046.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 046<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 047====== | ======Slide 047====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s047.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 047]] | + | [[Image:L02_s047.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 047<br> |

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

======Slide 048====== | ======Slide 048====== | ||

| − | [[Image:L02_s048.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 048]] | + | [[Image:L02_s048.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 048<br> |

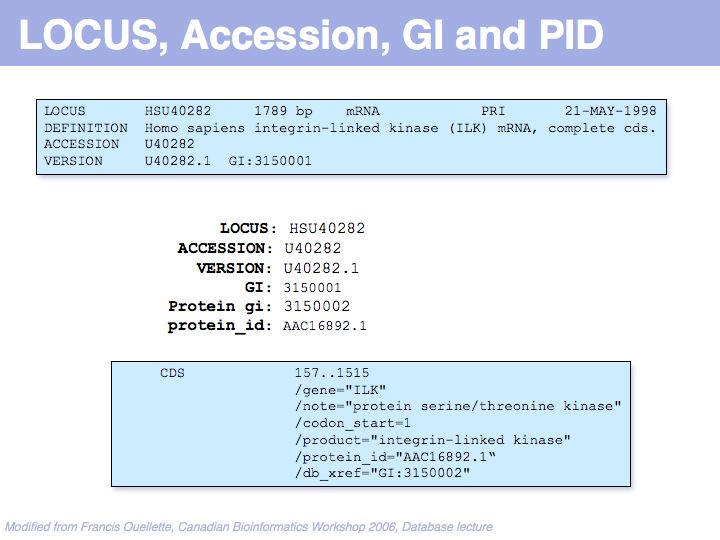

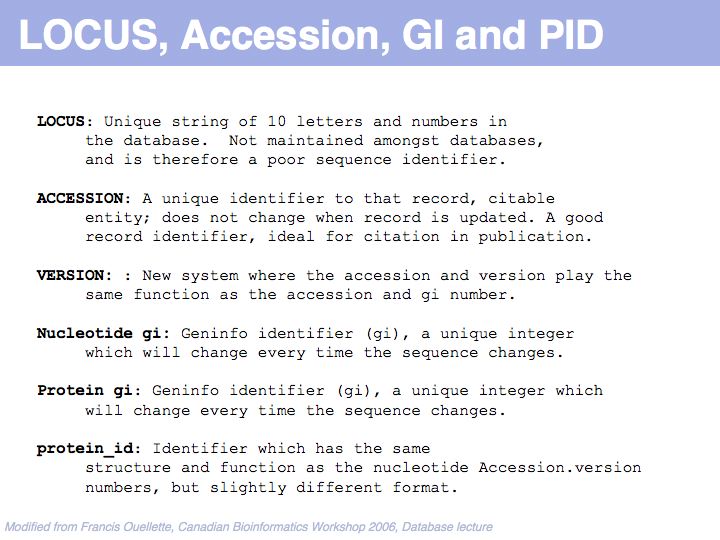

| + | Go [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/viewer.fcgi?db=nuccore&id=4594 '''here for a GenBank'''] record example; go [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/viewer.fcgi?db=protein&id=6320957 '''here for a GenPept'''] record example. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ======Slide 049====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s049.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 049<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 050====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s050.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 050<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 051====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s051.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 051<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 052====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s052.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 052<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

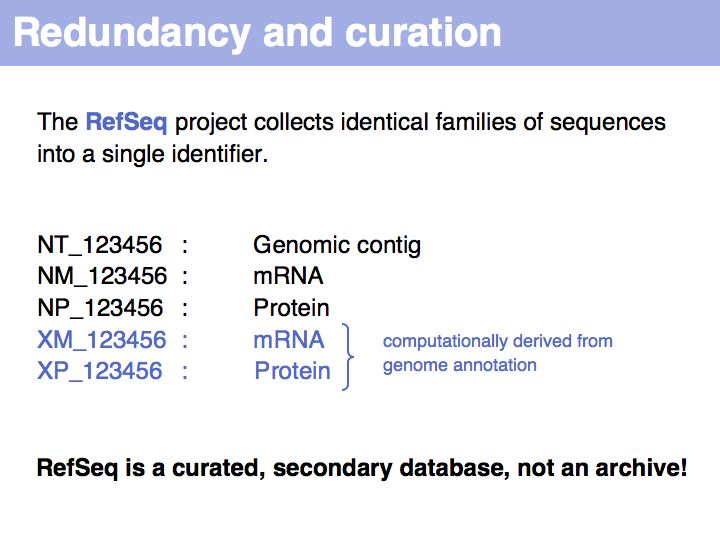

| + | ======Slide 053====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s053.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 053<br> | ||

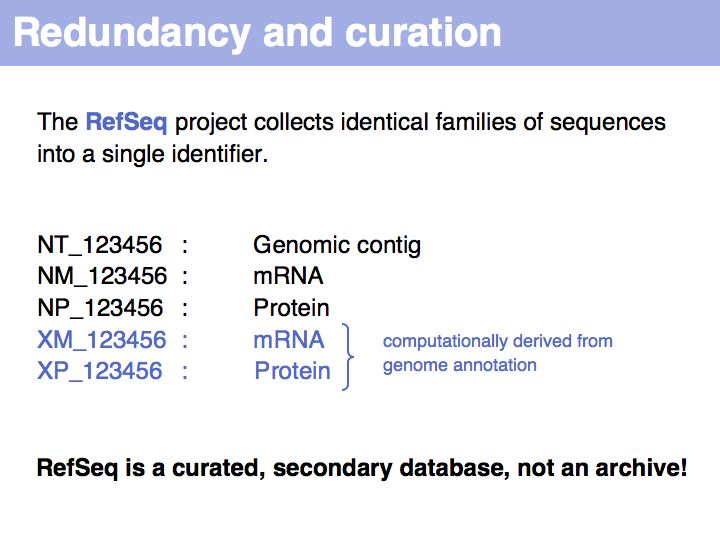

| + | see: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/RefSeq/ | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ======Slide 054====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s054.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 054<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 055====== | ||

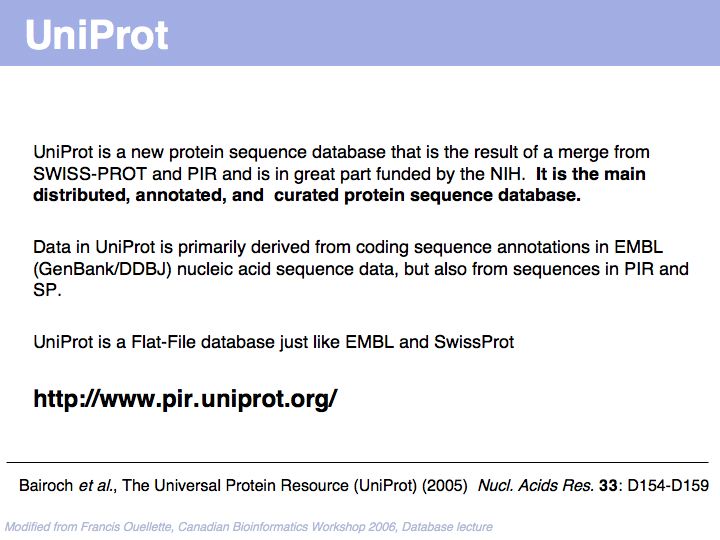

| + | [[Image:L02_s055.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 055<br> | ||

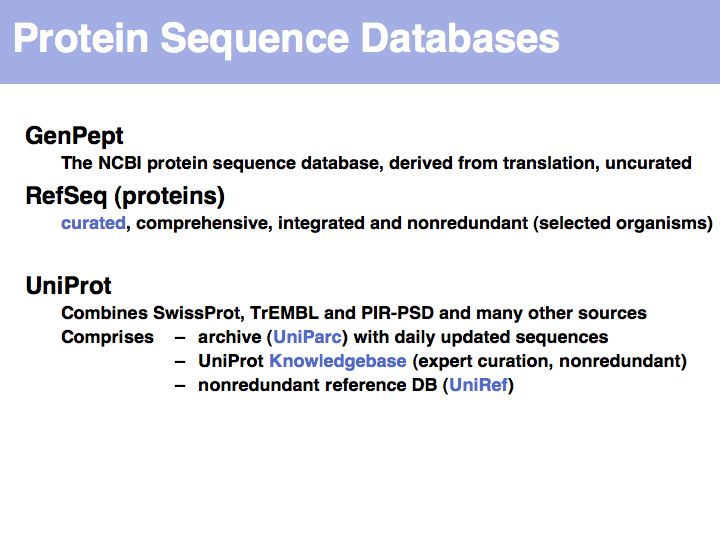

| + | UniProt is arguably the more comprehensive resource, however it is '''not''' integrated with the GenBank world, although that would be reasonably straightforward to do. For example, neither does the [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/viewer.fcgi?db=protein&id=6320957 NCBI record for the Swi4 protein] contain a reference to the UniProt accession number, nor does the [http://www.pir.uniprot.org/cgi-bin/upEntry?id=SWI4_YEAST UniProt record for the same protein] contain an NCBI accession number or a GI. National database politics are not always in the best interest of the worldwide scientific community. | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 056====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s056.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 056<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 057====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s057.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 057<br> | ||

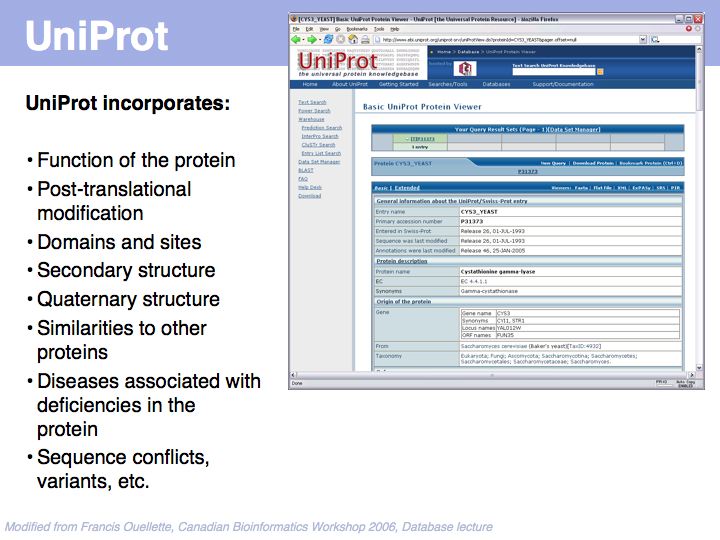

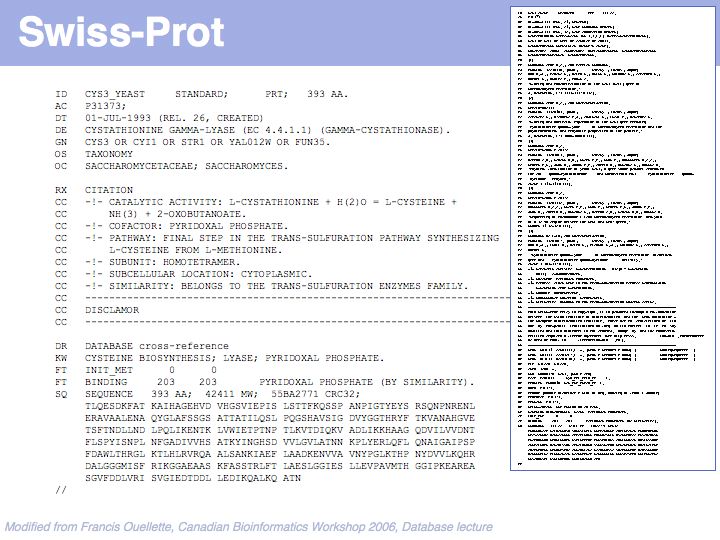

| + | SwissProt records - a subset of the UniProt Knowledge Base - are the highest standard, manually curated, non-redundant protein records available. Unfortunately the growth of the sequence databases far exceeds any human curation capabilities! | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 058====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s058.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 058<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 059====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s059.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 059<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 060====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s060.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 060<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 061====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s061.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 061<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 062====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s062.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 062<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | ======Slide 063====== | ||

| + | [[Image:L02_s063.jpg|frame|none|Lecture 02, Slide 063<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <small>[[Lecture_01|(Previous lecture)]] ... [[Lecture_03|(Next lecture)]]</small> | ||

Latest revision as of 14:57, 19 September 2007

(Previous lecture) ... (Next lecture)

The Sequence Abstraction

- What you should take home from this part of the course

- Know the one-letter code and key properties of all 20 proteinogenic aminoacids;

- Understand the benefits and limitations of the sequence abstraction;

- Recognize common sequence identifiers, utilize them confidently;

- Know about the contents of key sequence databases;

- Be able to retrieve sequence data;

- Know about and confidently use the fields in GenBank and GenPept records.

- Links summary

- IUPAC (Wikipedia)

- adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine (Wikipedia)

- SMILES (Wikipedia)

- Rob Russel's Amino Acid Pages

- GO (Gene Ontology)

- Open Biology Ontologies

- FASTA format

- Genbank Overview

- A GenBank record example

- A GenPept record example

- A UniProt record example

- Exercises

- Find a protein that contains a selenocysteine residue (e.g. human glutathione peroxidase). Check the Genbank record to see how this residue is represented in the sequence and in the record. Find and compare the corresponding SwissProt record.

- Find a secreted protein such as E. coli beta-lactamase. Look into the Genbank record whether you can identify the signal-peptide that is post-translationally removed. Find the corresponding SwissProt entry and look for the annotation.

- Human mitochondrial proteins are translated according to a different genetic code from human nuclear proteins. Looking at the CDS of mitochondrial Cytochrome B (NC_001807), how would you know?

Lecture Slides

Slide 001

Slide 002

Slide 003

Lecture 02, Slide 003

In order to make biology computable, we have to clarify the concepts we are working with. This is useful even beyond the requirements of bioinformatics. It is an exercise in clarifying the conceptual foundations of biology itself. In many instances, definitions in current, common use are deficient, either because our current state of knowledge has gone beyond the original ideas we were trying to subsume with a term (e.g. gene, or pathway), or because an inconsistent formal and colloquial meaning of terms lead to ambiguities (e.g. function), or because the technical meaning of terms is poorly understood and generally misused (e.g. homology).

In order to make biology computable, we have to clarify the concepts we are working with. This is useful even beyond the requirements of bioinformatics. It is an exercise in clarifying the conceptual foundations of biology itself. In many instances, definitions in current, common use are deficient, either because our current state of knowledge has gone beyond the original ideas we were trying to subsume with a term (e.g. gene, or pathway), or because an inconsistent formal and colloquial meaning of terms lead to ambiguities (e.g. function), or because the technical meaning of terms is poorly understood and generally misused (e.g. homology).

Slide 004

Slide 005

Lecture 02, Slide 005

Asking about the best is an ill-posed question if the purpose is not specified. The best for what? There are many possible abstractions, each serving different purposes. Each of the abstractions above can serve as a representation of the biomolecule, each one emphasizes a different perspective and can serve a different purpose.

Asking about the best is an ill-posed question if the purpose is not specified. The best for what? There are many possible abstractions, each serving different purposes. Each of the abstractions above can serve as a representation of the biomolecule, each one emphasizes a different perspective and can serve a different purpose.

Slide 006

Lecture 02, Slide 006

Working with abstractions implies we are no longer manipulating the biological entity, but it's representation.This distinction becomes crucial, when we start computing with representations to infer facts about the original entities! Inferences must be related back to biology! Common problems include that the abstraction may not be rich enough to capture the property we are investigating (e.g. one-letter sequence codes cannot represent amino acid modifications or sequence numbers), or the abstraction may be ambiguous (e.g. one protein may have more than one homologue in a related organism, thus the relationship between gene IDs is ambiguous) or the abstraction may not be unique (e.g. one protein may have more than one function, the same protein name may refer to unrelated proteins in different species).

Working with abstractions implies we are no longer manipulating the biological entity, but it's representation.This distinction becomes crucial, when we start computing with representations to infer facts about the original entities! Inferences must be related back to biology! Common problems include that the abstraction may not be rich enough to capture the property we are investigating (e.g. one-letter sequence codes cannot represent amino acid modifications or sequence numbers), or the abstraction may be ambiguous (e.g. one protein may have more than one homologue in a related organism, thus the relationship between gene IDs is ambiguous) or the abstraction may not be unique (e.g. one protein may have more than one function, the same protein name may refer to unrelated proteins in different species).

Slide 007

Slide 008

Lecture 02, Slide 008

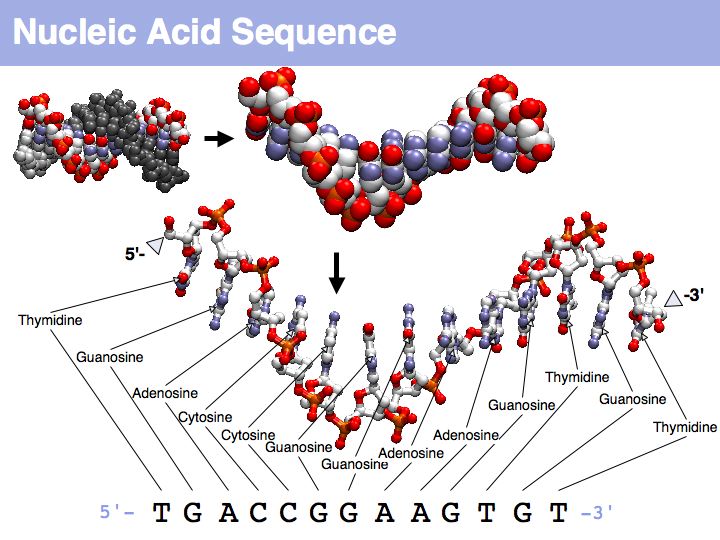

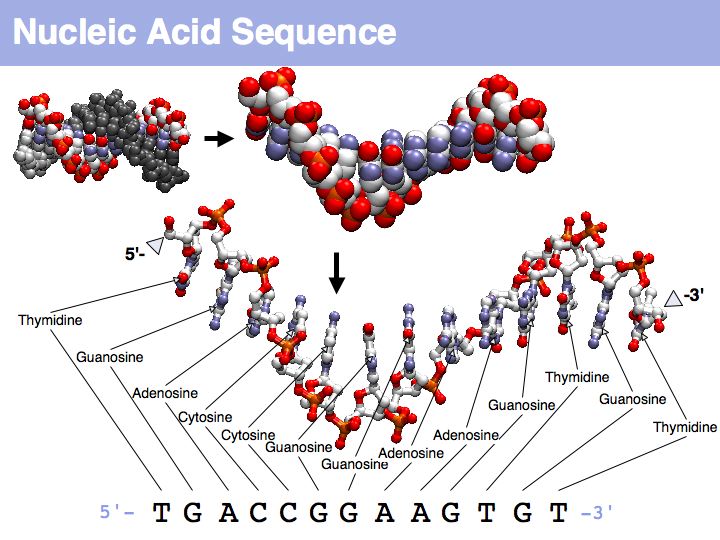

Nucleic acids can form heterocopolymers as DNA or RNA, thus their structural formula can be described (to a close approximation) simply by listing the nucleotide bases in a defined order. A one-letter code has been defined as a shorthand notation for this. By convention, DNA or RNA sequence is written in the direction from the bond with the 5' carbon of the ribose (or deoxyribose), to the bond with the 3'-carbon. Since the 5'-carbon carries a free 5'-phosphate at the terminus of the polynucleotide and the 3'-carbon carries a free OH, this direction happens to be the same direction that nucleic acid polymers are replicated by the DNA-polymerase: a phosphate of a single nucleotide is attached to the free -OH of the polynucleotide. This direction is also the direction of transcription of the RNA polymerase (for the same reason) and (incidentally) the direction of translation by the ribosome. Due to base-pair complementarity, only one strand of a double stranded sequence needs to be recorded since the sequence of the complementary strand is implied: it is simply the reverse complement. The one letter abbreviations are defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as follows:

A = adenine

C = cytosine

G = guanine

T = thymine

R = G A (purine)

Y = T C (pyrimidine)

K = G T (keto)

M = A C (amino)

S = G C (strong bonds)

W = A T (weak bonds)

B = G T C (not A)

D = G A T (not C)

H = A C T (not G)

V = G C A (not T)

N = A G C T (any)

Nucleic acids can form heterocopolymers as DNA or RNA, thus their structural formula can be described (to a close approximation) simply by listing the nucleotide bases in a defined order. A one-letter code has been defined as a shorthand notation for this. By convention, DNA or RNA sequence is written in the direction from the bond with the 5' carbon of the ribose (or deoxyribose), to the bond with the 3'-carbon. Since the 5'-carbon carries a free 5'-phosphate at the terminus of the polynucleotide and the 3'-carbon carries a free OH, this direction happens to be the same direction that nucleic acid polymers are replicated by the DNA-polymerase: a phosphate of a single nucleotide is attached to the free -OH of the polynucleotide. This direction is also the direction of transcription of the RNA polymerase (for the same reason) and (incidentally) the direction of translation by the ribosome. Due to base-pair complementarity, only one strand of a double stranded sequence needs to be recorded since the sequence of the complementary strand is implied: it is simply the reverse complement. The one letter abbreviations are defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as follows:

A = adenine

C = cytosine

G = guanine

T = thymine

R = G A (purine)

Y = T C (pyrimidine)

K = G T (keto)

M = A C (amino)

S = G C (strong bonds)

W = A T (weak bonds)

B = G T C (not A)

D = G A T (not C)

H = A C T (not G)

V = G C A (not T)

N = A G C T (any)

Slide 009

Lecture 02, Slide 009

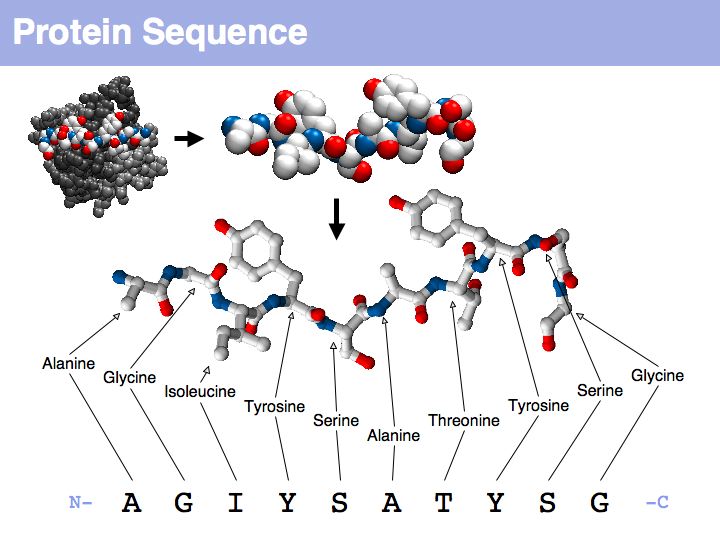

Proteins are amino acid heterocopolymers, thus their structural formula can be described (to a close approximation) simply by listing their constituent amino acid residues in a defined order. The one-letter code is a shorthand notation for this. By convention, protein sequence is written from aminoterminus (N-) to carboxyterminus (C-). This happens to be the same direction in which the protein is synthesized on the ribosome.

Proteins are amino acid heterocopolymers, thus their structural formula can be described (to a close approximation) simply by listing their constituent amino acid residues in a defined order. The one-letter code is a shorthand notation for this. By convention, protein sequence is written from aminoterminus (N-) to carboxyterminus (C-). This happens to be the same direction in which the protein is synthesized on the ribosome.

Slide 010

Slide 011

Slide 012

Lecture 02, Slide 012

An amino acid is a molecule. A number of abstractions are in common use for this molecule: its chemical formula simply describes the elemental composition, a so called SMILES string (see also here) captures bonding topology as well, its information is equivalent to a chemical graph. A set of records of 3D coordinates can describe the three-dimensional conformation, this can in turn be displayed in a number of different image options - like a simple line drawing or a set of spheres, color coded by element, with relative sizes corresponding to the elements' Van der Waals radii.

An amino acid is a molecule. A number of abstractions are in common use for this molecule: its chemical formula simply describes the elemental composition, a so called SMILES string (see also here) captures bonding topology as well, its information is equivalent to a chemical graph. A set of records of 3D coordinates can describe the three-dimensional conformation, this can in turn be displayed in a number of different image options - like a simple line drawing or a set of spheres, color coded by element, with relative sizes corresponding to the elements' Van der Waals radii.

Slide 013

Slide 014

Slide 015

Slide 016

Lecture 02, Slide 016

Hydrophobic amino acids - the group FAMILYVW - are found predominantly in the core of a protein, small amino acids such as GASC are often found in turns, charged amino acid sidechains - (+):KRH and (-)DE - are almost exclusively found on the surface; the energetic requirements for desolvation of the sidechain makes their incorporation into the core unfavourable.

Hydrophobic amino acids - the group FAMILYVW - are found predominantly in the core of a protein, small amino acids such as GASC are often found in turns, charged amino acid sidechains - (+):KRH and (-)DE - are almost exclusively found on the surface; the energetic requirements for desolvation of the sidechain makes their incorporation into the core unfavourable.

Slide 017

Lecture 02, Slide 017

Cysteine can take on a number of different roles, depending on its context. Here, cysteine forms part of the active site, it is the nucleophile in the catalytic triad C-H-N; cathepsin is thuss an example of a cysteine-protease. This particular cysteine is absolutely conserved in related proteins.

Cysteine can take on a number of different roles, depending on its context. Here, cysteine forms part of the active site, it is the nucleophile in the catalytic triad C-H-N; cathepsin is thuss an example of a cysteine-protease. This particular cysteine is absolutely conserved in related proteins.

Slide 018

Slide 019

Lecture 02, Slide 019

Cysteine can also be found in a very general role, simply as a somewhat polar, small residue. This general role is infrequent in secreted proteins since it can interfere with the formation of the correct disulfide topology and generally makes the protein sensitive to oxidation. Such cysteines are poorly conserved in related proteins.

Cysteine can also be found in a very general role, simply as a somewhat polar, small residue. This general role is infrequent in secreted proteins since it can interfere with the formation of the correct disulfide topology and generally makes the protein sensitive to oxidation. Such cysteines are poorly conserved in related proteins.

Slide 020

Lecture 02, Slide 020

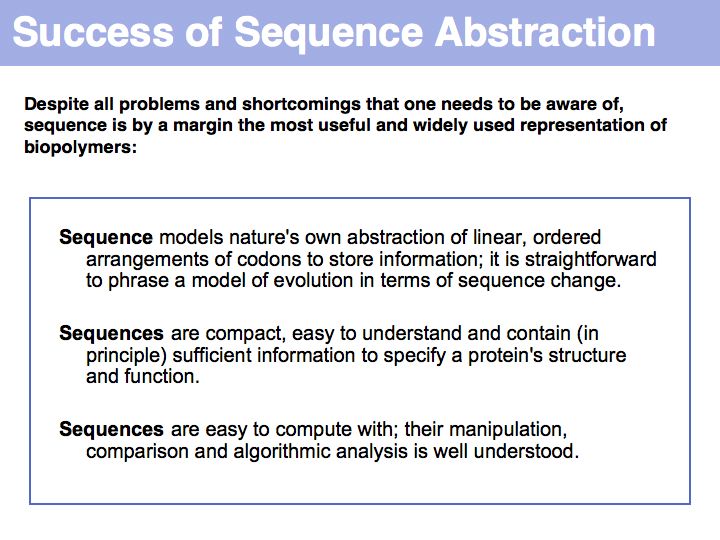

Sequence is the most important abstraction in biology; you need to know your amino acids in order to relate a sequence back to the biopolymer. Required knowledge is: the structural formula, the one- and three- letter codes and key properties (such as charge, relative size, polarity) for all 20 proteinogenic amino acids. A resource that summarizes amino acid properties is at http://speedy.embl-heidelberg.de/aas/

Sequence is the most important abstraction in biology; you need to know your amino acids in order to relate a sequence back to the biopolymer. Required knowledge is: the structural formula, the one- and three- letter codes and key properties (such as charge, relative size, polarity) for all 20 proteinogenic amino acids. A resource that summarizes amino acid properties is at http://speedy.embl-heidelberg.de/aas/

Slide 021

Lecture 02, Slide 021

In Shakespeare's classic tragedy of romantic love and family allegiance, Juliet encapsulates the play's central struggle in this phrase by claiming that Romeo's family name is an artificial and meaningless convention. Just like in the world of the sequence abstraction, this is only partially true: the problems are not just based in the fact that Romeo is called a Montague, but that he is in fact a member of that family. Even if a Thing does not change if it's abstract label changes, such labels rarely exist in isolation: other Things might be referred to by the same label and changing one changes the composition of the entire set. (Or, to remain with our example, as soon as Romeo renounces his name and thus his family, the family would be no longer the same.) Even worse - and this is something we encounter every day in bioinformatics - if identifiers are not stable over time, cross-references to that identifier fail. If you decide you'll call a rose a skunk, people would become very confused.

In Shakespeare's classic tragedy of romantic love and family allegiance, Juliet encapsulates the play's central struggle in this phrase by claiming that Romeo's family name is an artificial and meaningless convention. Just like in the world of the sequence abstraction, this is only partially true: the problems are not just based in the fact that Romeo is called a Montague, but that he is in fact a member of that family. Even if a Thing does not change if it's abstract label changes, such labels rarely exist in isolation: other Things might be referred to by the same label and changing one changes the composition of the entire set. (Or, to remain with our example, as soon as Romeo renounces his name and thus his family, the family would be no longer the same.) Even worse - and this is something we encounter every day in bioinformatics - if identifiers are not stable over time, cross-references to that identifier fail. If you decide you'll call a rose a skunk, people would become very confused.

Slide 022

Slide 023

Slide 024

Slide 025

Slide 026

Slide 027

Lecture 02, Slide 027

Often synonym constrained controlled vocabularies are presented as option lists on Web forms. If the CV is too long for this approach to be practical, defining the correct form becomes a challenge. In well engineered databases a lot of effort is spent on this task; typically a large dictionary of synonym mappings is employed in some form.

Often synonym constrained controlled vocabularies are presented as option lists on Web forms. If the CV is too long for this approach to be practical, defining the correct form becomes a challenge. In well engineered databases a lot of effort is spent on this task; typically a large dictionary of synonym mappings is employed in some form.

Slide 028

Lecture 02, Slide 028

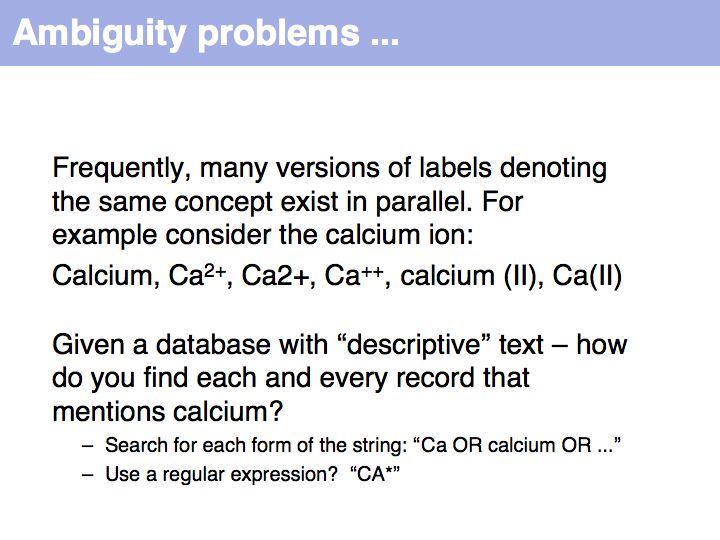

NB. The situation that a unique property of an entity can be concisely described is the ideal case: in that case the identifier captures the most fundamental aspect of the molecule. For calcium, the element does not just have the atomic number 20, it is the element with 20 protons. Similarly oxytocin does not just have the sequence CYIQNCPLG, it is the peptide with that sequence. However, these are favourable exceptions and more commonly unique, abstract labels - such as identifiers - have to be defined.

NB. The situation that a unique property of an entity can be concisely described is the ideal case: in that case the identifier captures the most fundamental aspect of the molecule. For calcium, the element does not just have the atomic number 20, it is the element with 20 protons. Similarly oxytocin does not just have the sequence CYIQNCPLG, it is the peptide with that sequence. However, these are favourable exceptions and more commonly unique, abstract labels - such as identifiers - have to be defined.

Slide 029

Slide 030

Slide 031

(deleted)

Slide 032

Slide 033

Lecture 02, Slide 033

Read more about the FASTA format.

Read more about the FASTA format.

Slide 034

Slide 035

Slide 036

Slide 037

Slide 038

Slide 039

Slide 040

Slide 041

Slide 042

Slide 043

Slide 044

Lecture 02, Slide 044

see: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/GenbankOverview.html

see: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/GenbankOverview.html

Slide 045

Slide 046

Slide 047

Slide 048

Slide 049

Slide 050

Slide 051

Slide 052

Slide 053

Lecture 02, Slide 053

see: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/RefSeq/

see: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/RefSeq/

Slide 054

Slide 055

Lecture 02, Slide 055

UniProt is arguably the more comprehensive resource, however it is not integrated with the GenBank world, although that would be reasonably straightforward to do. For example, neither does the NCBI record for the Swi4 protein contain a reference to the UniProt accession number, nor does the UniProt record for the same protein contain an NCBI accession number or a GI. National database politics are not always in the best interest of the worldwide scientific community.

UniProt is arguably the more comprehensive resource, however it is not integrated with the GenBank world, although that would be reasonably straightforward to do. For example, neither does the NCBI record for the Swi4 protein contain a reference to the UniProt accession number, nor does the UniProt record for the same protein contain an NCBI accession number or a GI. National database politics are not always in the best interest of the worldwide scientific community.

Slide 056

Slide 057

Slide 058

Slide 059

Slide 060

Slide 061

Slide 062

Slide 063