Difference between revisions of "BIN-SYS-Concepts"

m |

m |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | <div id=" | + | <div id="ABC"> |

| − | + | <div style="padding:5px; border:1px solid #000000; background-color:#b3dbce; font-size:300%; font-weight:400; color: #000000; width:100%;"> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Systems Models | Systems Models | ||

| + | <div style="padding:5px; margin-top:20px; margin-bottom:10px; background-color:#b3dbce; font-size:30%; font-weight:200; color: #000000; "> | ||

| + | (Systems Models) | ||

| + | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Smallvspace}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | + | <div style="padding:5px; border:1px solid #000000; background-color:#b3dbce33; font-size:85%;"> |

| − | <div | + | <div style="font-size:118%;"> |

| − | + | <b>Abstract:</b><br /> | |

<section begin=abstract /> | <section begin=abstract /> | ||

| − | + | The functional composition of individual biomolecules to "systems" faces challenges from incomplete data for "bottom up" approaches, and incomplete knowledge for "top down" approaches. This unit discusses the issues, explains the concept of reverse engineering higher order functions from basic components and demonstrates strategies for architectural modelling of systems. | |

| − | The functional composition of individual biomolecules to "systems" faces challenges from incomplete data for "bottom up" approaches, and incomplete knowledge for "top down" approaches. This unit discusses the issues, explains the concept of reverse engineering higher order functions from basic components and demonstrates | ||

<section end=abstract /> | <section end=abstract /> | ||

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | <!-- ============================ --> | |

| − | + | <hr> | |

| − | + | <table> | |

| − | == | + | <tr> |

| − | === | + | <td style="padding:10px;"> |

| − | + | <b>Objectives:</b><br /> | |

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

This unit will ... | This unit will ... | ||

* ... introduce a definition of biological '''systems'''; | * ... introduce a definition of biological '''systems'''; | ||

| Line 58: | Line 28: | ||

* ... present examples of how this system is presented in different databases; | * ... present examples of how this system is presented in different databases; | ||

* ... teach how to apply reverse engineering principles, guided by the concept of a "system architecture", to categorize system components, define their functional relationships, and illustrate categories and functions in an informative diagram; | * ... teach how to apply reverse engineering principles, guided by the concept of a "system architecture", to categorize system components, define their functional relationships, and illustrate categories and functions in an informative diagram; | ||

| − | + | </td> | |

| − | + | <td style="padding:10px;"> | |

| − | + | <b>Outcomes:</b><br /> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

After working through this unit you ... | After working through this unit you ... | ||

* ... can identify key components of the yeast G1/S cell cycle switch by name and role; | * ... can identify key components of the yeast G1/S cell cycle switch by name and role; | ||

* ... are familar with concepts of systems modelling; | * ... are familar with concepts of systems modelling; | ||

* ... can abstract and organize factual knowledge to a sytems architecture diagram. | * ... can abstract and organize factual knowledge to a sytems architecture diagram. | ||

| + | </td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| + | <!-- ============================ --> | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | <b>Deliverables:</b><br /> | ||

| + | <section begin=deliverables /> | ||

| + | <li><b>Time management</b>: Before you begin, estimate how long it will take you to complete this unit. Then, record in your course journal: the number of hours you estimated, the number of hours you worked on the unit, and the amount of time that passed between start and completion of this unit.</li> | ||

| + | <li><b>Journal</b>: Document your progress in your [[FND-Journal|Course Journal]]. Some tasks may ask you to include specific items in your journal. Don't overlook these.</li> | ||

| + | <li><b>Insights</b>: If you find something particularly noteworthy about this unit, make a note in your [[ABC-Insights|'''insights!''' page]].</li> | ||

| + | <section end=deliverables /> | ||

| + | <!-- ============================ --> | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | <section begin=prerequisites /> | ||

| + | <b>Prerequisites:</b><br /> | ||

| + | You need the following preparation before beginning this unit. If you are not familiar with this material from courses you took previously, you need to prepare yourself from other information sources:<br /> | ||

| + | *<b>Metabolism</b>: Enzymatic catalysis and control; reaction sequences and pathways; chemiosmotic coupling; catabolic- and anabolic pathways. | ||

| + | *<b>Cell cycle</b>: Replication control and mechanism; phases of the cell-cycle; checkpoints and apoptosis. | ||

| + | This unit builds on material covered in the following prerequisite units:<br /> | ||

| + | *[[FND-MAT-Graphs_and_networks|FND-MAT-Graphs_and_networks (Graphs and Networks)]] | ||

| + | <section end=prerequisites /> | ||

| + | <!-- ============================ --> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Smallvspace}} |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Smallvspace}} | ||

| − | + | __TOC__ | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Vspace}} | {{Vspace}} | ||

| Line 85: | Line 72: | ||

=== Evaluation === | === Evaluation === | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<b>Evaluation: NA</b><br /> | <b>Evaluation: NA</b><br /> | ||

| − | :This unit is not evaluated for course marks. | + | <div style="margin-left: 2rem;">This unit is not evaluated for course marks.</div> |

| + | == Contents == | ||

| + | {{Smallvspace}} | ||

| + | <div style="padding: 15px; background: #F0F1F7; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA; font-size:125%;color:#444444"> | ||

| + | ;A theory can be proved by an experiment; but no path leads from experiment to the birth of a theory. | ||

| + | ::''<small>(Variously attributed to Albert Einstein and Manfred Eigen)</small>'' | ||

| + | </div> | ||

{{Vspace}} | {{Vspace}} | ||

| + | Systems biology is about '''systems''' ... but what is a system, anyway? Definitions abound, the recurring theme is that of connected "components" forming a complex "whole". Complexity describes the phenomenon that properties of components can depend on the "context" of a component; the context is the entire system. That fact that it can be meaningful to treat such a set of components in isolation, dissociated from their other environment, tells us that not all components of biology are connected to the same degree. Some have many, strong, constant interactions (often these are what we refer to "systems"), others have few, weak, sporadic interactions and thus can often be dissociated in analysis. Given the fact that complex biological components can be perturbed by any number of generic environmental influences as well as specific modulating interactions, it is non-trivial to observe that we '''can''' in many cases isolate some components or sets of components and study them in a meaningful way. A useful mental image is that of clustering in datasets: even if we can clearly define a cluster as a number of elements that are strongly connected to each other, that usually still means some of these elements also have some connections with elements from other clusters. Moreover, our concepts of systems is often hierarchical, discussing biological phenomena in terms of entities or components, subsystems, systems, supersystems ... as well, it often focusses on particular dimensions of connectedness, such as physical contact, in the study of complexes, material transformations, in the study of metabolic systems, or information flow, in the study of signalling systems and their higher-order assemblies in control and development. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At the end of the day, a biological system is a '''conceptual''' construct, a model we use to make sense of nature; nature however, ever pragmatical, knows nothing of systems. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this sense systems biology could be dismissed as an artificial academic exercise, semantics, even molecular mysticism, if you will (and some experimentalists do take this position), '''IF''' systems biology were not curiously successful in its predictions. For example, we all know that metabolism is a network, crosslinked at every opportunity; still, the concept of pathways appears to correlate with real, observable properties of metabolite flux in living cells. Nature appears to prefer constructing components that interact locally, complexes, modules and systems, in a way that encapsulates their complex behaviour, rather than leaving them free to interact randomly with any other number of components in a large, disordered bag. | ||

| − | + | The mental construct of a "system" thus provides a framework for concepts that describe the '''functional''' organization of biological components. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | {{Vspace}} | |

| − | |||

{{Task|1= | {{Task|1= | ||

| Line 108: | Line 103: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td> | <td> | ||

| − | Draw a system architecture diagram to represent the function of either | + | Draw a system architecture diagram<ref>Some of these were the topic of an in-class quiz in 2016, with an alloted time of 15 minutes. Try hard not to take longer.</ref> to represent the function of either |

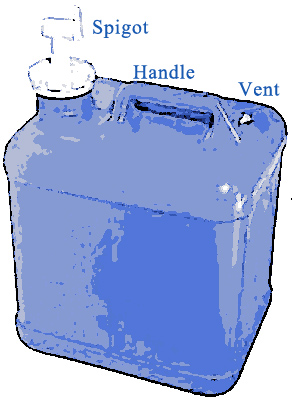

* a water canister (cf. the image at the side); | * a water canister (cf. the image at the side); | ||

* a bicycle; | * a bicycle; | ||

| − | * an anteater; | + | * [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anteater an anteater]; |

| − | * a hockey puck; | + | * [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hockey_puck a hockey puck]; |

| − | * | + | * [http://pdb101.rcsb.org/motm/72 F<sub>1</sub>F<sub>o</sub>-ATP Synthase]; |

| − | * a desk | + | * [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Task_lighting a desk light]; or |

| − | * a cookbook | + | * a cookbook. |

Prepare your diagram by clearly defining and listing purpose, input, output and interfaces, feedback control and other structural and behavioural elements. Draw a draft on a separate piece of paper first, then prepare a legible sketch of your diagram. Don't overcomplicate your diagram: 10 to 15 elements will be plenty. | Prepare your diagram by clearly defining and listing purpose, input, output and interfaces, feedback control and other structural and behavioural elements. Draw a draft on a separate piece of paper first, then prepare a legible sketch of your diagram. Don't overcomplicate your diagram: 10 to 15 elements will be plenty. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A Google Doc with a systems architecture template is linked [https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1L-QpRGCa3nE5jmr4tYB-yEEnFtfYrcMA6U530aql7as/edit?usp=sharing '''here''']. You can access it and make a copy for your own use. | ||

| + | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

| − | <td>[[ | + | <td>[[Image:Water_canister.jpg]]</td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| Line 126: | Line 124: | ||

{{Vspace}} | {{Vspace}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

{{Vspace}} | {{Vspace}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<div class="about"> | <div class="about"> | ||

| Line 197: | Line 141: | ||

:2017-11-08 | :2017-11-08 | ||

<b>Version:</b><br /> | <b>Version:</b><br /> | ||

| − | :1 | + | :1.1 |

<b>Version history:</b><br /> | <b>Version history:</b><br /> | ||

| + | *1.1 Expanded | ||

*1.0 First live version | *1.0 First live version | ||

*0.1 First stub | *0.1 First stub | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{CC-BY}} | {{CC-BY}} | ||

| + | [[Category:ABC-units]] | ||

| + | {{UNIT}} | ||

| + | {{LIVE}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<!-- [END] --> | <!-- [END] --> | ||

Latest revision as of 05:32, 23 September 2020

Systems Models

(Systems Models)

Abstract:

The functional composition of individual biomolecules to "systems" faces challenges from incomplete data for "bottom up" approaches, and incomplete knowledge for "top down" approaches. This unit discusses the issues, explains the concept of reverse engineering higher order functions from basic components and demonstrates strategies for architectural modelling of systems.

|

Objectives:

|

Outcomes:

|

Deliverables:

Prerequisites:

You need the following preparation before beginning this unit. If you are not familiar with this material from courses you took previously, you need to prepare yourself from other information sources:

- Metabolism: Enzymatic catalysis and control; reaction sequences and pathways; chemiosmotic coupling; catabolic- and anabolic pathways.

- Cell cycle: Replication control and mechanism; phases of the cell-cycle; checkpoints and apoptosis.

This unit builds on material covered in the following prerequisite units:

Contents

Evaluation

Evaluation: NA

Contents

- A theory can be proved by an experiment; but no path leads from experiment to the birth of a theory.

-

- (Variously attributed to Albert Einstein and Manfred Eigen)

Systems biology is about systems ... but what is a system, anyway? Definitions abound, the recurring theme is that of connected "components" forming a complex "whole". Complexity describes the phenomenon that properties of components can depend on the "context" of a component; the context is the entire system. That fact that it can be meaningful to treat such a set of components in isolation, dissociated from their other environment, tells us that not all components of biology are connected to the same degree. Some have many, strong, constant interactions (often these are what we refer to "systems"), others have few, weak, sporadic interactions and thus can often be dissociated in analysis. Given the fact that complex biological components can be perturbed by any number of generic environmental influences as well as specific modulating interactions, it is non-trivial to observe that we can in many cases isolate some components or sets of components and study them in a meaningful way. A useful mental image is that of clustering in datasets: even if we can clearly define a cluster as a number of elements that are strongly connected to each other, that usually still means some of these elements also have some connections with elements from other clusters. Moreover, our concepts of systems is often hierarchical, discussing biological phenomena in terms of entities or components, subsystems, systems, supersystems ... as well, it often focusses on particular dimensions of connectedness, such as physical contact, in the study of complexes, material transformations, in the study of metabolic systems, or information flow, in the study of signalling systems and their higher-order assemblies in control and development.

At the end of the day, a biological system is a conceptual construct, a model we use to make sense of nature; nature however, ever pragmatical, knows nothing of systems.

In this sense systems biology could be dismissed as an artificial academic exercise, semantics, even molecular mysticism, if you will (and some experimentalists do take this position), IF systems biology were not curiously successful in its predictions. For example, we all know that metabolism is a network, crosslinked at every opportunity; still, the concept of pathways appears to correlate with real, observable properties of metabolite flux in living cells. Nature appears to prefer constructing components that interact locally, complexes, modules and systems, in a way that encapsulates their complex behaviour, rather than leaving them free to interact randomly with any other number of components in a large, disordered bag.

The mental construct of a "system" thus provides a framework for concepts that describe the functional organization of biological components.

Task:

- Read the introductory notes on Concepts of systems modelling

Task:

|

Draw a system architecture diagram[1] to represent the function of either

Prepare your diagram by clearly defining and listing purpose, input, output and interfaces, feedback control and other structural and behavioural elements. Draw a draft on a separate piece of paper first, then prepare a legible sketch of your diagram. Don't overcomplicate your diagram: 10 to 15 elements will be plenty. A Google Doc with a systems architecture template is linked here. You can access it and make a copy for your own use. |

|

Notes

- ↑ Some of these were the topic of an in-class quiz in 2016, with an alloted time of 15 minutes. Try hard not to take longer.

About ...

Author:

- Boris Steipe <boris.steipe@utoronto.ca>

Created:

- 2017-08-05

Modified:

- 2017-11-08

Version:

- 1.1

Version history:

- 1.1 Expanded

- 1.0 First live version

- 0.1 First stub

![]() This copyrighted material is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Follow the link to learn more.

This copyrighted material is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Follow the link to learn more.